David Bowie’s tranquil voice seeps in over a black screen, waxing poetic philosophy about the infinity and complexity of time. Letters incrementally fade in one by one out of order. First an O, then an I, until it’s complete: “BOWIE.” Like a black hole, its gravity feels inescapable. And the film’s hardly even begun.

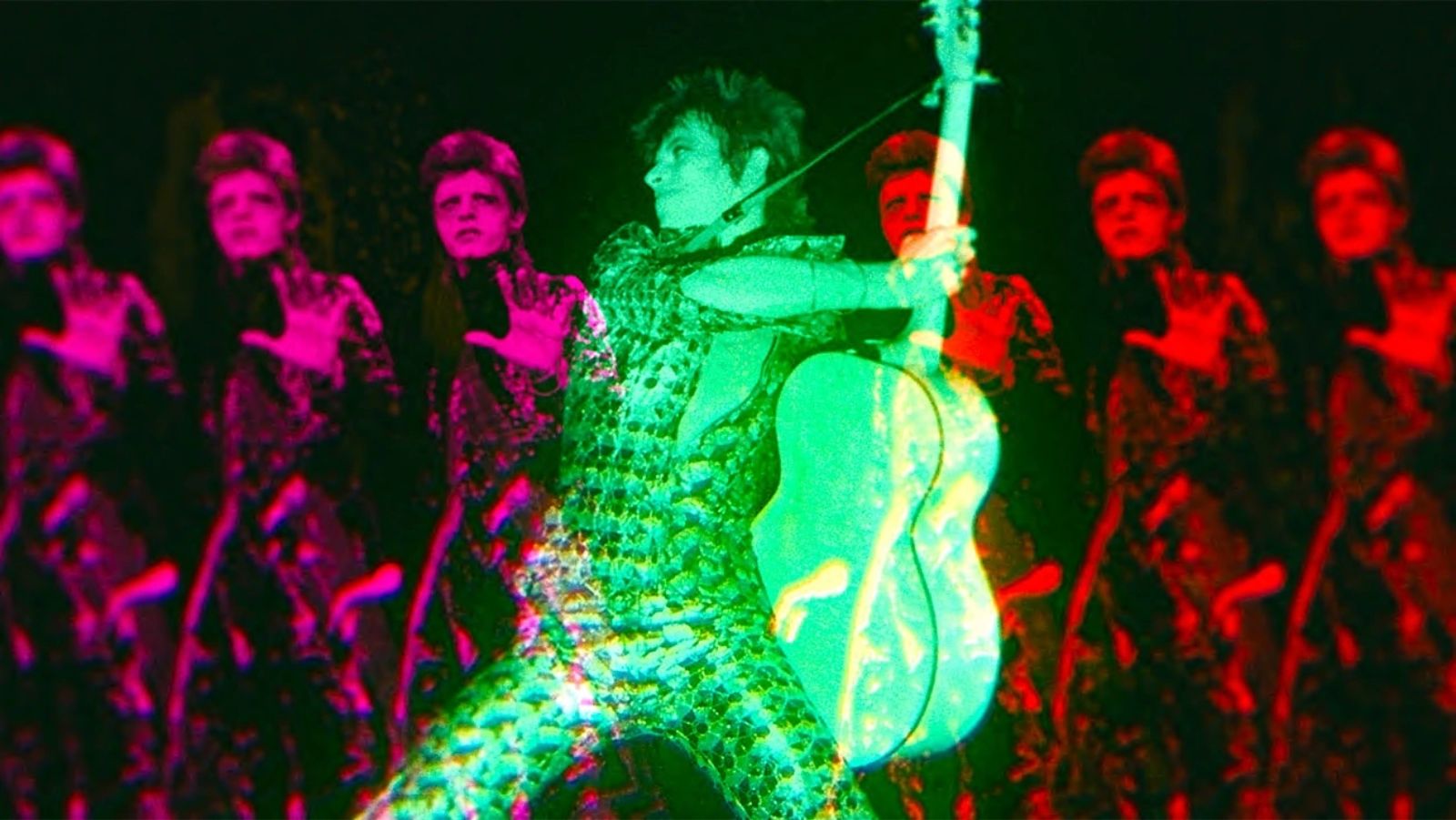

Brett Morgen—venerated documentarian behind Cobain: Montage of Heck and Jane—is the first filmmaker to land a project sanctioned by the Bowie estate. He did not take this for granted. Moonage Daydream is a radiant, psychedelic voyage through the artist’s life, soul, and work that offers a novel approach, gobs of unseen footage, and cosmic insight into Bowie’s ontologies from the demigod himself.

Per Morgen, “Bowie cannot be defined, [but] he can be experienced.” A better musician, writer, performer, painter, sculptor, actor, and multimedia artist than most, Bowie was an unparalleled fountain of imagination and work ethic. The London-born artistic savant recorded 26 studio albums, acted in more than 20 films, appeared in 128 music videos, and this only covers music and film. Needless to say, a comprehensive Bowie doc would need a Ken Burns runtime, which would leave plenty to the imagination. At a lengthy 140 minutes, the film flashes by. The deeper you go the more you want to know, and the more there is to know.

Morgen accordingly takes a more surreal, hallucinatory approach to the icon, leaning into the chaos of life Bowie implores us to embrace, not flee. He employs a flurry of pop-culture imagery, animation, and clips from Bowie’s favorite works (e.g. Metropolis, which inspired his third album The Man Who Sold the World). More important is footage from Bowie’s performances, films, music videos, paintings, Broadway stint, et al. in concert with interviews (no talking heads), sound bites, and quote cards to flesh out his foundational philosophies. The idea is to communicate how and why Bowie lived, a more apt way of bottling him into a feature that gives viewers real sense of who he was more than a futile attempt to capture all ever could.

Since the release of “Space Oddity” in 1968, the world has taken Bowie’s cue in calling him an alien. In earnest, it’s the most accurate word. And nothing will make you more sure of that than Moonage Daydream. Morgen presents Bowie-as-martian in myriad ways, primarily because there’s so much to pull from. Bowie explored the theme of outer space and his own extraterrestrial nature tirelessly throughout his career, writing songs, painting portraits, making music videos, and starring in movies about it, like Nicolas Roeg’s revered The Man Who Fell to Earth, a film he was born to lead in title alone. But he was just as alien in his worldview and the way he behaved.

Bowie had a singular curiosity about life on Earth, an insatiable desire for people and culture and art. It manifested in every aspect of him: the way he dressed, the vast range of work he created, the tendency to move from city to city to dislodge comfort and spur creativity, the approach to sexuality, the work ethic he maintained until his death in 2016, the belief in a supernatural “energy force” that he didn’t subject to religiosity, the communities he kept, the humility he could somehow radiate through supreme confidence. The list could go on for pages. In the 1970s he was asked by a Christian TV host what he worshiped. His response was simple: “life.” And it shows.

How well he treats everyone also sticks out across the footage. In interviews he always answers sincerely, clearly, kindly, and with mutual respect. Interviewers unfairly corner him, twist his words, or show plain disrespect, and he effortlessly refuses to sink to their level. He doesn’t scoff at their words or speak down to them out of a warped sense of celebrity. He gives them the time of day, makes eye contact, and listens, just as a martian in love with humanity—or perhaps Mr. Rogers—might. Then he proceeds to be patient and measured in his response. The consistent generosity of spirit is as inspiring as all the art, frankly. It proves that Bowie’s lasting impact, his innate singularity, went way beyond the work. He had the weight of the world on his shoulders and upheld a high standard of compassion. If he could do it, why can’t we?

Next time you hit a creative block, Moonage Daydream is your medicine. The section on his creative processes is a goldmine of ideas. Bowie constantly changed his writing procedure, shirking the myth there’s a “right” way to work well. It was essential to his evolution as an artist. He’d shower himself with creative limitations until he came up with something new, largely relying on instinct. He would write separate songs and cut up the paper to mix the lyrics, or shuffle the instrumentation of melodies he’d already written, or rely fully on improvisation, or switch art forms altogether. Once he felt settled somewhere he’d move to a new country to keep his artistic mind fresh—the US, Germany, Japan.

He was a relic of a star from a time when the most popular artists were such because they organically drew the greatest attention. And they drew it because they were the most original, most daring, most different—the polar opposite of modern pop music aiming to cash in on trained, commercially bred talent and formulaic singles ripped from past successes and fashioned from market research.

As Bowie relays from his 50-plus years of professional experience in arts and entertainment, one must “have integrity to work outside the system.” He would keep creating until the outcome was something that provided a sense of fulfillment and meaning. He just wanted to “work well,” not popularly, and that’s why he was huge. In Bowie’s own terms, creating art is “not about discovery. The search is the thing.” The creation of art, not art itself, gives purpose.

Bowie inspires us to be as curious about the world as he was—to try things, create, think differently, be comfortable with being uncomfortable, grow, evolve. If nothing else (ha!), he was an agent of change, a king among catalysts. And the energy of a man who feels empty when he’s not changing and / or creating is quite contagious, especially a man who felt securely destined to change the world as a teen. If we’re honest about the finite time we have here and embrace life as an opportunity to be curious, like Bowie, who knows what could happen? At the very least it gives the artistic, emotional, existential freedom to create.

Perhaps the only thing that could make Moonage Daydream better is an IMAX theater, which is in the works. Get ready.

Moonage Daydream premiered at the Cannes Film Festival and opens in September.