The Dean Silvers Indies

BLACKBOOK Magazine

A New York independent film producer bucks Hollywood convention and humbles the studio drones

By Betsy Berne

What type of person comes to mind when you hear “movie producer”—or “lawyer,” for that matter? A slick, trashy, fast-talking schmoozer? Well, none of the above describes New York film producer/lawyer Dean Silvers. Except fast-talking. I had to concede exhaustion after a few hours of rapid-fire free association, but Silvers grinned. “Sorry,” he said. “I do this to people.”

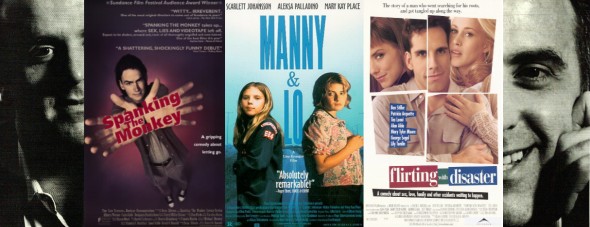

Instead, picture a Brooklyn born and raised modern day Jesus Christ as a film producer/lawyer and you’ve got Dean Silvers, the man behind such highly regarded independent films as Spanking the Monkey, Manny & Lo, The Last Good Time, Wingstock, and Flirting With Disaster. Virtually everyone who’s worked with him is in accord. How many times can you hear it fervently said “He’s an original” or “Dean is his own man” or “He protects the director’s vision” and not become suspicious? When Klaus Volkenborn, executive producer of The Last Good Time, became the fourth person to say “He’s one of the most honest people I’ve ever met,” I felt myself capitulating. And when Jeremy Davies, star of the film Spanking the Monkey, insisted, “Everything you hear is true. Dean is the only person in this business for whom I would drop everything to work with,” I had no choice but to become another Dean Silvers disciple.

A strong streak of irreverence coupled with a dark sense of the absurd saves Silvers from appearing an overly earnest Pollyanna. Not coincidentally, these attributes run smack through the middle of every film he’s produced. In 1993, Silvers gained his first experience as a hands-on, top-dog feature producer with the award-winning film Spanking the Monkey, written and directed by David O. Russell (making his debut as a feature director). If you don’t already know, Spanking the Monkey is a film that is laugh-out-loud funny about the dead serious, not to mention taboo, subject of incest between a mother and a son. Russell had been shopping around the script for months and no one had managed to find the humor—Hollywood and a comedy about incest? You can imagine. Already fairly discouraged, he was dining one night with Silvers, his lawyer and close friend, when the latter finally leapt up saying, “Oh, let’s just do it.” Silvers said that when he read the script he couldn’t resist becoming involved. “David is a brilliant writer who makes you feel uncomfortable in a comic way: He makes you laugh and cringe simultaneously.” After a harrowing fifteen hours a day for twenty-four days shoot (it was “like flogging a dead horse at the end,” says Silvers), and an equally intense post-production, the film went on to win the Audience Award at Sundance for Best Film. Silvers became “somebody” and began to get the calls and receive scripts.

Dean Silvers is unassuming and a bit self-deprecating, with a slight Woody Allenish-tone in his voice. At the office, he is dressed down in khakis and polo shirt and shows few signs of wear and tear; save for a little hair loss. And once he starts talking, this Brooklyn-bred man displays amazing energy. (Davies says, “Meeting with Dean is like stepping in front of a firing line at a fireworks display—he knocks you off your feet and he lifts you up.”) You better listen carefully, too, because there isn’t a lot of excess verbiage.

Silvers is a literary film producer—an anomaly in the business—admitting to a voracious reading habit. When prodded, he confesses that he would rather read a book than see a movie. “When you read a lot as a kid, you develop the imagination of a nickelodeon. When I read a script, it’s like that nickelodeon, with each page like a scene turning faster. I see pages like pictures from a movie in my head.” (It wasn’t until college that Silvers became interested in movies, primarily as a dating device. And after seeing Bergman’s Cries and Whispers, he knew what to do.)

The fact that Silvers is so well-read may be one key to his normalcy-is-deviant/deviance-is-normal sensibility and why his films are of unusually high quality and not easily categorized. He goes after the moments in life you can’t really rationalize or put into words—moments that may be painful or all wrong but unavoidable if you’re going to experience life with your nerve endings exposed. “Dean doesn’t read a lot of scripts, and the ones he does read he reads carefully.” Says Lisa Kreuger, director of Manny & Lo. “In my script, I had written something where a lot happens in image instead of dialogue, and Dean picked up on that automatically while a lot of other producers didn’t. After those producers kept telling me I should make certain things clearer sooner, I finally took their advice and made changes in the script. When Dean read it, he said ‘it was better when it was more subtle, with more left unsaid.’ He doesn’t go for the Hollywood put-your-cards-on-the-table immediately thing.”

Silvers is a tried-and-true New Yorker: You won’t see him moving out West to do that L.A. thing. “On Dean’s birthday, he called me to tell me he wouldn’t be in the office because every year he walks all around the city by himself thinking over the past year and what he’ll do next,” reports Krueger. Now that is something—the dedicated New Yorkers I know usually have trouble merely getting out the door to hail a cab, particularly on a birthday. While finishing up his master’s degree Silvers met an ABC production executive who told him, “You don’t seem like the kind of guy who gets coffee for people, so why don’t you get a law degree and at least you won’t be a gofer.” Silvers not only got a law degree but pulled in a Ph.D. in communications and the media as well. Then he called back the ABC bigwig and found that no one would hire him with all those degrees and no experience. So he started a one-man law firm specializing in arts and entertainment—without an office. “I knew all the great pay phones in Manhattan,” he says. “One of my favorites was at the Waldorf. There were flowers and plenty of free paper and pens. My expenses consisted of dimes and quarters.”

Silvers had some slow years where he was barely getting by, but he never despaired of his ultimate goal as a film producer. He believes in serendipity and that “Life is a joke, but a good joke”—a sentiment echoed in all of his films. He points to one particular moment that changed the course of his life and can only be described as serendipitous. He was perspiring in a Forest Hills steam bath next to another sweaty fellow who coerced him into getting involved as a producer for a purported rock-variety show. Naively, Silvers jumping in with both feet, only to realize the man was a fraud, the show was a pipe dream, and he’d been ripped off. In the process, however, he met another producer named George Harrison (not the Beatle) who, in turn, introduced him to his future wife, Marlen Hecht. In this particular scenario, she is the woman behind the man. Hecht is a deceivingly delicate, tiny-boned powerhouse, who adamantly refuses to divulge her age. Having grown up in Washington Heights she is, like Silvers, a nature New Yorker. She co-produced Manny & Lo and Wingstock with Silvers—working behind the scenes on the other films—and she also owns the post-production company, Teatown Video, Inc., which she self-started and which is one of the largest woman-owned post-production companies today. Teatown is conveniently located one flight down from Silver’s office, and the two trot up and downstairs all day. The Hecht-Silvers team is a ninties version of Ozzie and Harriet. Hecht agrees they’ve never had traditional roles, adding wryly, “I’m the one who has had to stop and give birth.” Of course, their two children are now the focal point. Krueger says there were often times in the editing room when one of the kids would call, and while one parent solved the crisis, the other went right on working.

“I didn’t have a clue on how to make a movie when we started Spanking,” says Silvers, but others beg to differ. When Silvers and Russell began to run out of cash in the middle of the shoot, they showed dailies to Cheryl Miller Houser, vice-president of production at Buckeye Entertainment, to try to conjure up more money to finish the film. “When I saw the dailies, they were so fabulous that I went right to the head of Buckeye,” says Houser. “and I convinced him to put up the money, a fraction of what we would usually invest in development. I said, ‘Why not put the finishing funds into a film that’s already happening, especially such a unique one?’ And I was impressed with Dean as a person. He’s so un-Hollywood; he doesn’t care what people think. He’ll pour his heart and soul and energy into his projects. Once he says yes, he won’t stop until it’s done.”

It was a tough shoot with a $200,000 budget, a young, inexperienced crew that wasn’t getting paid up front, and Silvers learning as he went along. Ellen Parks, the casting director for Silvers’ films says “Spanking was a labor of love. There was a real excitement, a wonderful sense of partnership amongst us. Dean is incredibly passionate about his friends and the people he chooses to work with, along with being viscerally attached.” Hecht concurs, adding “David Russell has a uniquely wry sense of humor, which is hard to capture. It’s not like you’re making an action movie. When you’re directing, everyone wants to bang you down, but Dean helped interpret David’s vision and encouraged him. Keeping him focused on his goals. Dean is like a rock—he has absolute faith and provides real security.” For Davies, the film’s scrawny star, Silvers provided even more. “I couldn’t eat during the shoot and I lost ten pounds. Dean would sit me down and make protein shakes and force me to eat pizza.”

After the success of Spanking the Monkey, among the calls that came in was one from Bob Balaban, the director of Parents, an offbeat black comedy. He is also an actor—a veteran of Seinfeld, among other things—and currently working on Woody Allen’s upcoming project. Balaban was making The Last Good Time, a small budget ($800,000) film reminiscent of Louis Malle’s Atlantic City about a romance between a seventy-year-old man and a twenty-year-old girl/woman. It’s a real Dean Silvers kind of thing, a story about universal human conditions—in this case, loneliness, isolation, and death. Again, there’s that slow buildup of discomfort and comedy that feels uncannily like real life.

Balaban says he hooked up with Silvers because he needed someone who was “willing to do an unusual thing, someone who had a little off-center taste, and I’d heard he was the kind of guy who wasn’t just interested in making money. Unfortunately, Goldwyn, the film’s distributor, was going bankrupt when it was released. Well, life being what it is…” Balaban adds, smiling, “Dean always likes to make a brief appearance in his films for good luck. So we made sure to put him in, but you can only see his shadow. Maybe if we had made it a full frontal shot, we would have had better luck and made more money.”

The film did well critically, garnering some awards and creating a buzz, enough to make the people behind the film Wigstock go running to Silvers to help resuscitate a sinking ship. Silvers, in his first official collaboration with Hecht, whipped Wigstock into shape. Hecht says their partnership works well because their strengths and weaknesses don’t overlap; Silvers is good with the actual production, while Hecht has keen visual sense as an editor. When Silvers was approached by Krueger with her Manny & Lo script, it made sense to continue the partnership. “I was sending my script to a lot of different people. They’d be wildly enthusiastic during the meeting, and then I wouldn’t hear back,” Krueger says. “Then I met with Dean, and I walked away from the meeting thinking he seemed like a nice guy but not with any sense that he was interested. The next think I knew, Marlen and he were hot on the trail.”

Michelle Satter, the director of the Feature Film Program at Sundance (and another Silvers devotee), knew that Silvers was very interested in Krueger’s script and that he understood the quality of the material in terms of the marketplace. “Lisa came to me and said, ‘What do you think?’ because other producers were talking higher level budgets,” says Satter. “And I said, ‘Lisa, he’s going to make your film—I can’t say that about most people, that they’ll actually do it—so make the film.’ Dean really fought for Lisa’s vision. When you’re dealing with a low budget and a short amount of time to shoot in, producers often make the wrong trade-offs. But Dean is relentless when it comes to protecting the director.”

They began shooting by the seats of their pants. Although all the finances were not in place, Silvers wanted to take the risk and get started. Being who he is, he did not want to let the project sit and fester.

In Krueger’s words, the film concerns “what a family is made of, whether it goes beyond issues of choice and freedom or if it’s about something deeper and more primal.” Not only was the film about family, but the production was a family enterprise. Krueger had two stipulations: that her brother shoot the film and that Mary Kay Place, an actress who had become like family through performing in a Sundance workshop version of Manny & Lo, play her original role. In turn, Silvers had a demand: that they shoot in New York so that he could be with his family. The film is dedicated to Silvers’ father, who had recently passed away. And did I mention that starring in the opening scene is, well, Silvers’ family?

I don’t mean to be a spoilsport, but it’s almost too much: A film celebrating family values could easily result in sentimental slop. But in this case, we’re not talking election-time family values. In true Silvers style, the saving grace is that the family in Manny & Lo consists of two sisters who have run away from foster homes (one is sixteen, pregnant, and in denial), rob grocery stores, and end up adopting a home and kidnapping a mother. Krueger says matter-of-factly, “Look, the film was about developing trust, and my relationship with Marlen and Dean was about that, too. Given that the subject of the film was family, it made sense that the shoot was about it, too.” Krueger can’t stop gushing about Silvers; she admits it’s almost embarrassing, and no one can believe that she had such an idyllic experience with a first film. “Todd Solanz (director of Welcome to the Dollhouse) and I were on a panel together, and he was teasing me mercilessly when I raved. He kept telling me, “You’re crazy. Making Dollhouse was hell.”

After Manny & Lo, Silvers moved more steps up the ladder, working with Russell again on Flirting With Disaster—with a big cast of stars and a million-dollar budget. Not surprisingly, it’s another quirky story: Man gets itchy about his life and marriage, thinks he will solve it by finding his birth mother (he’s adopted), and sets off on a road trip complete with wife, new baby, and ‘other woman’ (adoption agent). A series of ribald misadventures ensue.

“My responsibilities had shifted. We had more money and box office actors. It was almost easier when we had no money and a cast of unknowns,” says Silvers. “We were dealing with studio people on the set which involved taking into consideration more layered responses.” Yet it was still a Silvers-value production.

Silvers’ law practice, which he still enjoys, is going strong, enabling him to take greater financial risks. But he has clearly become addicted to the movie business. Silvers enthuses, “I love getting into a new culture every time I do a new film. Now, I get very crazy to get into a new culture every six months. With Spanking, I thought a lot about incest and relationships. With The Last Good Time, I thought about death and loneliness. With Wigstock, I got into the alternative lifestyle, RuPaul and all. I learn so much.”

Currently, Silvers has four new projects going, thus four new cultures to delve into. He is working on a Brave/Independent Feature Channel pilot, a magazine-type show about independent filmmaking, written and directed by John Pierson (indie veteran and author of Spike, Mike, Slackers and Dykes). He is working with Krueger on her new script. He is developing the Isabelle Allende novel, Eva Luna, with Michael Radford (Il Postino) slated to direct. And he is set to embark on a new challege: He has written (in bits and pieces over the last seven to eight years) a film called Visionaries, which he is directing. It is a story about lost ideals and the sixties generation and is, as usual, a combination of several genres. Klaus Volkenborn, a co-producer, calls it a “mixture of Sneakers and The Big Chill.” Many of the Silvers disciples are on board: Davies, Ellen Parks as casting director, and Hecht as producer. As Davies says, “If Dean had sent me a scrap of paper saying this is his script, I would do it.”

In 1996, Variety magazine dubbed Silvers one of the rising independent producers in the country. With all these projects involving major talents and bigger budgets, I wonder if Silvers will go Hollywood and become one of those producers, a possibility his disciples adamantly deny. Volkenborn, who has worked with him from the beginning, doesn’t think so. “I was in Hollywood recently, and those people are not real. Dean is one hundred percent real as a person. We’ve become great friends which was strange for both of us—I’m German and he’s a Jew—and he had never had a German friend before. I’ll admit I had trouble understanding his humor at first.” (Silvers replied, “Well, I guess he didn’t get my Holocaust jokes.”) “He’s not just about business. He’ll call me up and ask how my grandmother is; he’s like my godfather,” offers Jeremy Davies.

Did Silvers harbor some secret desire to become a Hollywood big shot, a desire he was hiding from all his friends and associates? The only thing left was to go to the man: will all this success turn him into one of them? “I hope not,” he says simply. “I don’t want to sound like some New Agey person, but its been about timing and luck. The harder I work, the luckier I get.”

Bestsy Berne has written for The New Yorker, Vogue, and The New York Times Magazine.