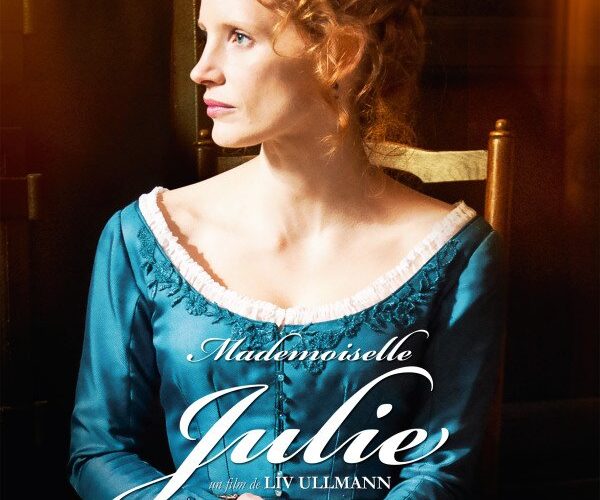

August Strindberg’s 1888 play Miss Julie traces the transference of indignity between two souls who share little more than a pervasive sense of unbelonging. Variously adapted by Alf Sjöberg and Mike Figgis, the play is perhaps suited to few filmmakers more than Liv Ullmann, muse and former partner of another titan of Swedish drama, Ingmar Bergman, whose career began with a screenplay written for Sjöberg and whose most significant collaboration with Ullmann, Persona, also observes one person’s anguish merging with another’s. Further spurring interest in this new Miss Julie is the striking physical resemblance between young Ullmann and her star, Jessica Chastain, who similarly projects vulnerability through her eyes and power through her voice.

But Ullmann’s film is a disappointment, transforming a delicate power play into an overheated shouting match. Ullmann reimagines the play in 1890 Ireland, on what is referred to more than in passing as a “midsummer’s night,” but the original text is kept largely unaltered, in part due to its insular nature: primarily a two-hander between John (Colin Farrell), the valet for a large country estate, and Julie (Chastain) the daughter of its owner, the film only allows for brief appearances by Kathleen (Samantha Morton), the estate’s cook and John’s shamed fiancée. Flirty with Kathleen and hostile with Julie, John’s resolve to stay dignified slowly crumbles in the face of Julie’s mocking advances. His shame then becomes Julie’s, complete with a humiliating gesture straight out of S&M.

Cinematographer Mikhail Krichman, best known for working with Leviathan director Andrei Zvyaginstev, occasionally hits on evocative imagery, like Farrell’s face in a window accompanied by Chastain’s reflection. One expressive long shot, fully encompassing the play’s complex power dynamic, shows what might have been: early in the film, as Kathleen stands and talks with John, Julie suddenly enters and slaps him, arrogantly holding herself above his betrothed, and Ullmann holds on the scene’s entirety. But a surplus of close-ups tells the audience more than they need to know. Reaction shots are the norm, and underscore how vital it is that the emotions running underneath John and Julie’s sparring matches remain unexpressed. Implicitly, the close-ups also position this theater adaptation as very anti-theatrical. This is quite an interesting tack to take, but Ullmann appears to be making no conscious effort to actively deconstruct theatricality; she simply creates emotional redundancy.

One also struggles to say the actors acquit themselves well. Close-ups do Farrell’s John no favors: his take on the character as an unwaveringly quivering mess at first seems merely one-note, but the mountains of lugubriousness put into a simple throwaway line like “I’m so tired” make the performance unintentionally campy. (His manic cries of “The bird!” in one memorable scene would fit snugly in a YouTube mash-up alongside a certain Nicolas Cage supercut.) Farrell is just one symptom of a general lack of restraint. As the play reaches its climax, Ullmann dials up the emotion: while Farrell is a time-bomb of angry lust, Morton’s Kathleen is a sulky prude, and Chastain’s Julie—marginally more restrained than her social inferiors by virtue of her class—vacillates wildly between hatred of John and resolve to escape her sheltered existence.

These contradictions would be beneficial if Ullmann kept the character’s complexities in check, but every time John and Julie embrace, their multi-directional loathing, so extreme elsewhere, seems to vanish. (For a contrasting portrait of love-hate passion, check out Jacques Doillon’s magnificently nuanced 2013 film, Love Battles.) Chastain is a remarkable actress, but the close juxtaposition of lines like “You’re disgusting” and “Yes, we’ll run away” register as downright comical when it’s so unclear whether Julie is consciously conflicted or intentionally provocative.

The tone of Ullmann’s Miss Julie is especially unfortunate because the play’s fine dissection of its characters’ hypocrisy can still be felt, whether in Kathleen’s gentle yet callous treatment of a dog forced to receive an abortive remedy, or John’s unresolved mixture of resentment and envy of the ruling class. The play unites John and Julie in their neurotic need to “never be a slave,” and it’s telling that both the baron of the estate and throngs of street people often referenced are left off-screen: the dual specters of being seen as poor and rich inflect John and Julie’s self-conceptions at every turn. But in this overly literal adaptation, we know invisible forces are at work only when characters directly address their presence.

Miss Julie premiered at TIFF. See our complete coverage below.