The farther we advance towards a world of complete convenience, the further we distance ourselves from self-sufficiency. Every new generation loses more skills and know-how of what humanity was capable of for millennia to survive. We choose careers in dance and the arts, leave books collecting dust when the internet is at our fingertips, and take comfort in the assumption we’re only minutes away from acquiring what we need so technology can continue sustaining us into the future. So what happens when the power goes out? What’s the next step when fail-safe after fail-safe fails to leave us fending for ourselves? Who survives and who doesn’t stand a chance?

These are the questions posed in Into the Forest, writer/director Patricia Rozema‘s adaptation of Jean Hegland‘s near-future, post-apocalyptic novel about two sisters isolated from civilization (and its fall) in the woodland seclusion of their home. Similar to The Road, this story isn’t necessarily concerned with the cataclysm or its potential to be fixed. It’s doesn’t worry about the outside chaos at a macro level or the death and void of decency we easily assume takes hold shortly after. All those things are important, but they don’t concern us regular folk on the ground. We lack the security clearance to help anyone but ourselves. Unprepared and out of our element, we’re all naive teens: paranoid, selfish, and scared.

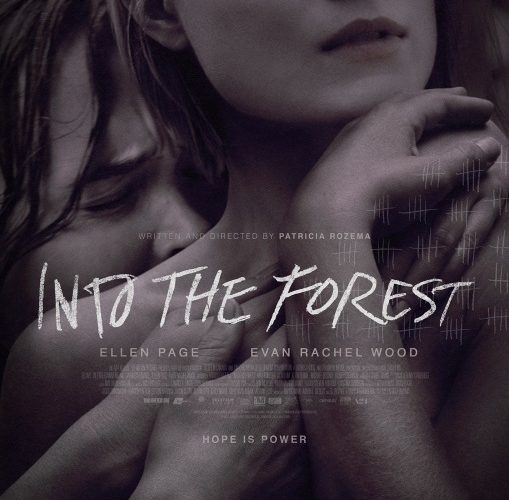

Meet Nell (Ellen Page, who spearheaded the effort to see this movie made after reading the novel on her local bookstore’s recommendation) and Eva (Evan Rachel Wood). Needing four gallons of gas to reach town and back from the beautiful home being fixed by their father Robert (Callum Keith Rennie), they’re beholden to the creature comforts they’ve taken for granted. The former studies for her SATs with her computer multitasking as a phone to connect with boyfriend Eli (Max Minghella) and the latter breathes dance in preparation for an upcoming audition. They are good-natured, passionate, and quick to cry foul when desire trumps common sense. Dad thankfully has the skills to make life comfortable without electricity, but he can’t protect them forever.

There are just three characters besides these sisters: Dad, Eli, and the store clerk in town (Michael Eklund‘s Stan) who helps procure gasoline and candles. When they decide to stay home and ride out the storm cinematically progressing months at a time, it was to escape one nightmare in order to be consumed by another. We’re so used to these types of stories unfolding on the road so we can catch glimpses of humanity falling apart that we at times forget Nell and Eva are virtually trapped in this house. During the day all seems normal if not a nostalgic look at the 1990s with books being read and metronomes used in lieu of iPod playlists. But then rations grow low and an accident removes their security blanket.

Half inspiring narrative of mankind’s perseverance, watching these girls teach themselves about nature and how to stay alive while severed from civilization is just that. The experience is tense, since we know this can’t be everything the story holds for us. They cannot live free from the violence and aggression we know simmers outside their forest surroundings with order thrown out the window. It’s not like no one knows where they are or that their home wouldn’t be seen as a target for supplies by passing drifters. Visitors are inevitable and while some remain pure at heart, others don’t. The film isn’t some last stand at the Alamo, though. It’s even worse because there isn’t a war or enemies to blame—just one person against another.

Questions are asked of these girls that they wouldn’t have needed to answer if the grid remained on. Priorities shift as happiness takes a backseat to desperation and fears move from innocently dreaming of success to the possibility a reunion with one’s boyfriend could result in an extra mouth to feed. While Hollywood pushes to show heroes against such “what if” adversity, Hegland and Rozema are more concerned in the truth that selfishness always rules our actions. Selfish desire doesn’t have to be malicious or beneficial to one at the expense of another—it merely explains how responsibility points inward. There’s no room for charity in a world whose infrastructure collapsed because those in need will simply take without repercussion.

Into the Forest is therefore also a nail-biter of suspense asking if or when these two young girls will die. Starvation, boredom, stir-crazed lunacy, or uninvited guests could all supply this end and many come very close to doing exactly that. The journey is nuanced and subtle, though, just like its science-fiction premise. So don’t expect a thrill a minute. I think the slow pace, despite its usually active subject matter, tripped up many people because inappropriate laughter and walkouts occurred throughout the TIFF screening I attended. Conversely, I appreciated the gradual burn and the intelligence utilized to reject the appeal of going bigger. Personal conflict is more attuned to what I’d face in these circumstances than Mad Max spectacle.

Rather than a show of force in a battle of brawn, survival here is about mental fortitude and enduring emotional pain. It’s about knowing when the fight is lost before it’s begun—of coming across shady men in the road with shotguns and a broken down car and realizing the only play is to back away and drive past. It’s about power turning to cowardice as the futility of an unplugged existence uncovers just how small you truly are. Some double down on their muscle, bullying and terrorizing to steal while others hunker down to learn and adapt. Ignoring what’s outside risks inviting it in and joining it costs your soul. Nell and Eva’s love for one another proves a potent weapon and the key to surviving both.

Into the Forest premiered at TIFF and opens on July 29.