Beautifully shot and impeccably directed, Exit Marrakech (also known in some territories as Morocco) is a stunning new film written and directed by Caroline Link (best known in the US for her Oscar-winning Nowhere in Africa and Beyond Silence). Link is a superb visual storyteller, essentially constructing a narrative that, at first glance, is somewhat problematic from an ethnographic perspective. Here is a film for a European audience, from the perspective of a young German discovering the “real Morocco” which stretches beyond a posh resort he’s confined to.

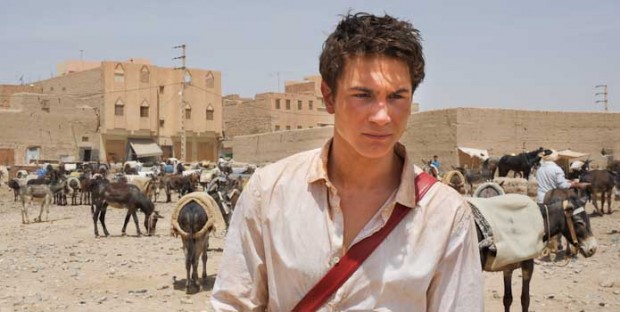

Ben, played by Samuel Schneider, graduates high school and is sent to live in Marrakech with her father, Heinrich (Ulrich Turkur). Heinrich is an avant-garde theater director, composing pieces that mix performance, video projections, and an outdoor amphitheatre. Naturally curious (the story makes it clear he’s a writer), Ben sets off with two stagehands and ventures to an underground dance club where no traditional women would be seen. There, Ben falls for a lovely young prostitute, Karima (Hafsia Herzi); after a brief tour of the city, Ben and Karima take a desert adventure which, essentially, could be considered a poverty tour.

But unlike, for instance, Lee Daniels’ Precious, Exit Marrakech is not exactly “poverty porn,” Morocco remaining Morocco in all its beauty and contradictions, here seen through European eyes. The evening I screened Exit Marrakech, I had an uncanny double feature: the first film I saw, The Summer of Flying Fish by Marcela Said, was a Chilean film about a territory in conflict told through the eyes of those living an everyday reality, but often ignoring it; Exit Marrakech, as told through German eyes, pieces together internal conflicts, realities, and images of poverty in a way that one could dismiss as arrogant. Morocco is essentially used a backdrop in a coming-of-age / family drama, yes, but what a rich one it is.

It’s a film which accurately captures the excitement of a young man testing the limits of both himself and his mostly absent father. It should be noted that, as an artist, Heinrich has no interest in “the real Morocco,” for the place does not inform his art practice. He accuses his son’s writings of being too sentimental, yet restricts his son from exploration. This German-centric view perhaps functions much in the same way Link’s Nowhere in Africa did — both are about Germans arriving to foreign lands and adapting. While Summer of Flying Fish is an insider’s tale, often when one is on the ground so long, having never left to observe situations from the outside, your perspective is murky.

Perhaps it’s problematic and simplistic to “consider” the plight of a young Moroccan prostitute, along with her family struggles — documented in several painful, nevertheless subtle scenes — from the perspective of a young German making sense of the world. Where this writer gives Exit Marrakech a pass is via its technical merits, the film proving a solid character-driven entertainment — engaging, beautiful, and well-crafted. While more classic films have eroticized the Middle East (including Casablanca), this and Nowhere in Africa serve a similar function: they are character-driven, uniquely European stories told in exotic landscapes. A friend of mine despises The Impossible, asking, “Why would I want to see a movie about how rich tourists were affected? I want to see what the locals went through.” I would recommend Exit Marrakech to him, even with a disclaimer attached.

Exit Marrakech screens at TIFF on September 5th, 6th and 15th. Watch the trailer above and click below for our complete coverage.