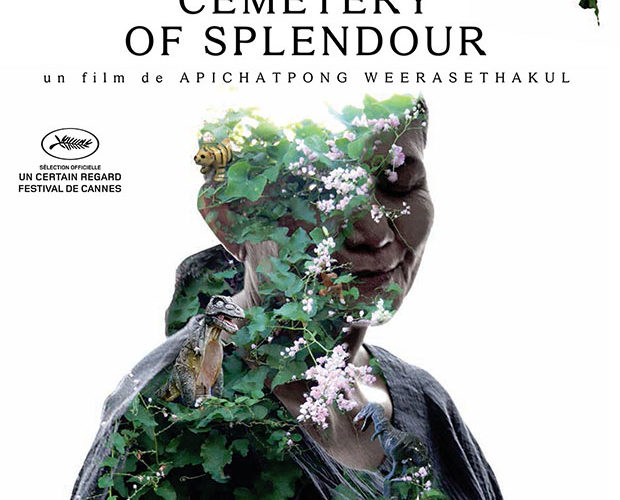

If it is by now redundant to say that Thai filmmaker Apichatpong Weerasethakul (who understands pronunciation troubles and insists people call him “Joe”) is truly in a class of his own, we might blame both the general excellence of his output — a large oeuvre consisting of features, shorts, and installations — and the difficulty that’s often associated with describing them in either literal or opinion-based terms. The further one gets into his work, however, the more his marriage of dense visual style with Thailand’s historical, spiritual, and mystical bedrocks will cohere. These images —often set in nature (with billowing winds and shaking trees adding to the atmosphere); almost always composed in long shot that emphasizes a self-conscious artificiality; and frequently running a few minutes each, sometimes several, to create a laid-back rhythm— are, for viewers Thai and non-Thai alike, a gateway to less-definitive thematic undercurrents. To put this in different terms for neophytes: observing his art is not at all unlike the intellectual stimulation of, say, confidently working through passages of a dense 19th-century novel.

On a piece-by-piece basis, Cemetery of Splendour is a bit more straightforward than Joe’s other work. Nothing here approaches the oddity of Uncle Boonmee’s cunnilingus-performing catfish or the intestine-eating characters from the sketch-like Mekong Hotel, and just about everything that might especially pique curiosity is still comprehensible in both narrative and emotional terms. This does not suggest that we’re dealing with a minor effort. In fact, his latest film is as enveloping as anything he’s ever made: a work that’s as darkly comic on subjects as specific as hospital regulation as it is sober-minded about perils as universal as comfortable living, one open to the possibilities of spiritual awakening while confronting us with questions of belief.

The plot, such as it is, takes place within and around a V.A. hospital in the Thai countryside. It’s a perpetually woozy place made palpable by the sounds of a military-supervised construction directly outside — among other things, Joe is a master of immersive audio — and an open, sun-baked ward where some unidentified sleeping sickness is afflicting patients. By the time we’re ingrained, concerned loved ones are consulting a medium and officials have begun installing machines that can supposedly read their dreams. (The science of this is inexact, but its spectacle is universal: neon lights creep up the cane-shaped tubes to signify activity, looking something like a psychedelic heart monitor.) Following scenes of observation, reflection, and the natural progression of life outside this hospital, particularly from the perspective of one nurse, a dialogue sequence — maybe the film’s longest — gradually reveals (or proposes; there are few absolutes here) that this epidemic is a result of the hospital having been built upon a cemetery of kings. These spirits are not only siphoning off these patients’ energy for use in their afterlife, but making communication — such as here, a rare bit of exposition.

If you can grasp that, are willing to be submerged into an overwhelming visual-aural exploration of Thai cityscapes and jungles, and have a taste for slow cinema, Splendour comes rather naturally. It helps that, in terms of “understanding” the project, Joe treats this single interaction as a pivot point and code for almost all else. But it’s not only a matter of everything working toward or growing from this single interaction; it’s that he’s also being playful, in part by book-ending the sequence with shots of life-size, plastic dinosaurs surrounding the location. There’s no shame in believing the unbelievable when so much of our natural world is filled with oddities both past and present; that building with sound and image is often our best source of comprehension, inexact as a tool thought it may be, is a source of excitement.

Yet its tone begins shifting toward desolation and decay. While still pleasurable, at times even rather funny, Cemetery is permanently marked by the possibility of an ailment made incurable by a solipsistic disrespect for the natural world. The picture thus goes quieter, darker, dispenses with most of its human figures, and ensures that whatever pleasures afforded by those neon lights must be taken hand-in-hand with the inactive bodies they’re ostensibly connected to. Whether one mode (unfurling and discovery) is clearly superior to the other (contemplation and recontextualization) matters less than the unified piece. This is a work built upon questions — questions it never ceases to ask, and none that are particularly less intriguing than the other. Why can one thing be grasped and why does another require imagination? What’s the difference between a miracle and a bill of goods? How can cinema bring us closer to these matters, their particulars, and any answer?

24 hours after an initial viewing, individual shots — none of which are wasted, even as Splendour becomes a tad less intriguing in regards to the conflicts within them — stick in the brain, each creating an association with another, and another, and another. I remain content with luxuriating in them, their overwhelming soundtrack, and the singular sense of vision that makes nearly everything indispensable; it’s okay to delay ineffable matters when there’s little reason to believe they’ll drift away.

Cemetery of Splendour is playing at TIFF and opens on March 4th.