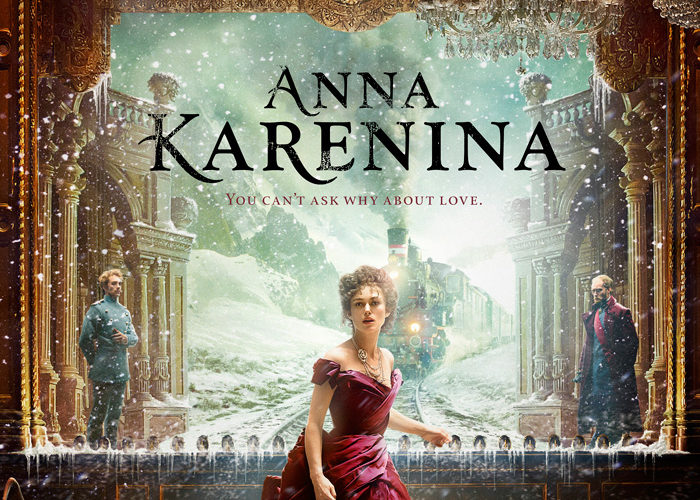

When TIFF director and CEO Piers Handling introduced the newest adaptation of Leo Tolstoy‘s Anna Karenina by saying director Joe Wright appropriately played up the theatricality of the novel, I wasn’t quite prepared for the blatant transparency where his stylistic approach’s artifice was concerned. As the camera lingers on a darkened stage covered by a place card to set the scene, I was blown away by the rising curtain uncovering a brilliantly conceived introduction to this TARDIS-like world much bigger on the inside than realistically possible. Russia—spanning St. Petersburg to Moscow—is captured by matte paintings and moving props, the tale of adulterous lust and aristocratic civility unfolding with Anna (Keira Knightley) readying to leave home and fix her brother’s marriage.

Like a Broadway musical without the singing, cities transition with relative ease as the camera meanders and zooms around new set pieces to make a home into an office into a restaurant and back again. But more than just changing the stage, busy streets are housed in the crowded catwalks above and at times even the auditorium seats are utilized as props in a show within the show. Besides a few edits to change our vantage point, the entirety of the film could be mistaken for an elaborate single take. Wright is famous for his uncut action and this maneuvering almost makes his scene of war-torn carnage in Atonement child’s play. And with a waltz around frozen figures animating as Anna passes recalling the long take party in Pride and Prejudice, the sheer magnitude of precision will take your breath away.

Existing within a very dated world, the visuals’ power to distract is crucial to forgiving the rather over-wrought plot behind it. Love is abundant amidst the government and military of 19th-century Russia, but unfortunately at the disregard of marriage’s bond. Beginning with Anna’s attempts to cajole her sister-in-law Dolly (Kelly Macdonald) into forgiving her brother’s (Matthew Macfadyen) straying eye, her arrival does much more than fulfill these goals. Her pragmatism towards adultery in this instant becomes the first domino to fall on the path of emotional thievery littering the proceedings. Brief glimpses at claimed souls they cannot have occur at a feverish pace and new unlawful relationships materialize for love as though a brand new concept never before thought real.

The meat of the plot therefore concerns Anna’s inevitable hypocrisy leading her into the arms of a younger man. Count Vronsky (Aaron Taylor-Johnson) finds his heart stolen while her weak attempts to dissuade pursuit only reveal mutual adoration. With her husband Alexei Karenin (Jude Law) as calculating and trusting as any man could be, her tryst continues unencumbered besides a pang of guilt and high society’s backstabbing rumor mill. Issues of God’s will come into play and characters well aware of their transgressions find themselves uncaring about their ramifications. At risk of being labeled a pariah—if not already—Anna and her lover willfully agree to live outside of decency, finding the stress and pressure of their positions an immovable weight on their souls.

Alongside technique, art direction, and atmosphere, the acting shines bright and the supporting players are their sun. Knightley and Taylor-Johnson give authentic lovesick performances in vital roles, yet our waning interest in their story hurts them overall. Law should probably be considered the third lead, but his Alexei remains on the outside looking in for so long that I’m unafraid to put him with the memorable periphery. So nuanced and internal, he is a beast of rage when finally allowing the repressed emotion building within out. Easily the most pitiable of the lot, his noble saintliness only ends up transforming him into a doormat. And that’s why it’s so wonderfully splendid whenever his Karenina meets the Count—we never know if he’ll be docile or fearsome.

Olivia Williams is perfectly cast as Vronsky’s mother while Macfadyen’s Oblonsky proves to be a highlight courtesy of a goofy demeanor and hilarious quips. The court jester of the bunch, his disastrous mistake in the annals of love that begins the chain of events to what’s ultimately a tragic end makes how he takes everything the least serious of all a pleasure. And then there’s the real couple of worth—Domhall Gleeson‘s Levin and hopeful bride Kitty (Alicia Vikander). Their bond is an uphill struggle derailed before it can begin, but their innocent novices in the ways of the heart makes us care more deeply in seeing success. Alternately, Anna and Vronsky are smitten at first sight with a relationship serving as the crux of the tale—it can never have that same type of spontaneity infused by the unknown.

The third act finds itself exceedingly drawn out, either due to the source material’s need to keep going or my 2012 mind thinking how lightly divorce is taken now. However, it’s this 19th-century set of stuffy rules that makes what Wright does visually the only way to tell its tale at present. Over-the-top melodrama performed as such could never be taken seriously today and period pieces have just become inherently stale. Making it all a spectacle lets us in on the joke by allowing a knowing wink to the novel’s age. We are able to watch sans eye rolling to soak up the technical genius and stage work for its aesthetic alone, tempering the problem of its story going too long by our delight to see more fluid transitions and theatrical magic. This is Wright at his most audacious and it suits him well.

Anna Karenina is now screening at TIFF and opens on November 16th.