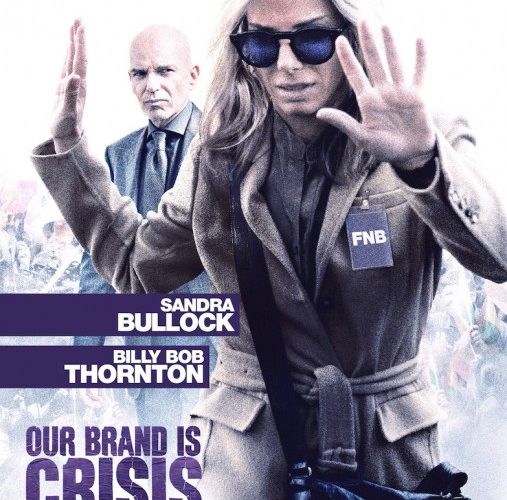

It’s probably because I know little about politics and care even less that I find most film’s dealing with the subject matter enjoyable. George Clooney‘s The Ides of March is one—the actor taking on the director’s chair, a co-screenwriting credit, and co-lead in front of the lens. Highly political himself with the media, it’s no surprise he’d gravitate towards a play based on an actual campaign (“Farragut North”) or a documentary doing much the same. The latter is Rachel Boynton‘s film centered on the 2002 Bolivian presidential election overseen by US firm Greenberg Carville Shrum’s marketing team of which the narrative Our Brand Is Crisis took both name and plot. Clooney was set to star here, too, before Sandra Bullock took a shine to the script.

Peter Straughan‘s fictionalization—the credits say “suggested by”—takes the behind the scenes happenings of Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada and Evo Morales’ race and transforms it into a satire as much about candidates Castillo (Joaquim de Almeida) and Rivera (Louis Arcella) as it is their American strategists (namely Bullock’s ‘Calamity’ Jane Bodine and Billy Bob Thornton‘s Pat Candy respectively). Rivera is winning in a landslide at the beginning with Castillo a hefty twenty-eight points back. So of course the underdog hires some outside assistance in Ben (Anthony Mackie) and Nell (Ann Dowd). But while they can handle organization and marketing with the help of Scoot McNairy‘s buffoon of an artistic director Rich, a seasoned veteran with the expertise and experience of victory on this scale can only help.

Intrigue enters straight away as this secret weapon of a consultant is introduced as a recluse suffering from the fear of being touched—or maybe this last part is a hyperbolic joke on behalf of Nell building her up to Ben since Jane Bodine doesn’t seem to care about shaking hands as much as opening herself up to people and in turn risking the possibility of ruining them on her path to victory. This is why she’s retired from the life to live in the mountains away from political chaos—this and the arch-nemesis whom she’s never defeated, Candy. Aware of this, Nell shrewdly ensures the newspaper photo depicting Jane’s potential opponent has that amoral devil by his side. It’s enough to coax her to South America.

Unfortunately these emotional hang-ups become window-dressing as she gradually exits her shell to get back into the swing of things. The ruthless nature that made her one of the best returns as she deftly notices her candidate Castillo is anything but the touchy-feely people person the campaign has thus far tried to force upon him. He’s already been President years before—hated during his term for privatizing the government—so voters know what they’re getting. Jane’s goal is to therefore spin the platform to fit him rather than the other way around. So she pitches the concept of a crisis, one so devastating that only a powerful, definitive man like Castillo can prevail. It’s a brilliant maneuver and soon works to further chip away at Jane’s soul.

She becomes nasty and devoid of boundaries—aspects she was hired to provide. She begins to make the race personal as though victory for Castillo and Bolivia meant little when compared to her own against Candy. The battle makes for entertaining skirmishes between them whether smug reversals of fortunate, expert gamesmanship twisting expectations, or quick-wittedly sarcastic verbal sparring, but it renders the numerous attempts at understanding the Bolivian masses superfluous. There’s one extended sequence where Jane and crew invites local volunteer Eduardo (Reynaldo Pacheco) and friends out to hear their opinions. You assume it’s to inspire her with a ground level enthusiasm to plug Castillo into the public consciousness, but it’s really just an excuse to get her drunk enough to get thrown in jail.

Don’t get me wrong, the notion of feeling out Eduardo and the disrespected indigenous population in the country does bring about a hopeful change by the conclusion—but it’s too little too late. If Jane is to earn redemption, she must do so before everything goes to Hell because letting it do so is what she’s sold her soul for in the first place. Straughan wants to get the best of both worlds by supplying the character’s rock bottom simultaneously with her epiphany to stop the bleeding within. All this does, though, is build her up to be the pragmatic winner her success needs. And that’s okay if they allow her to own it. Like Candy says, “You fight with monsters long enough and you eventually become one.”

There’s nothing wrong with this because this is the world of political campaigning. It chews you up and spits you out and those with the right mindset like Bodine and Candy excel. The humor arrives as a result of the absurd things they’ll do to get the upper hand—or it should be where the best laughs are. That night out on the town to get drunk also allows director David Gordon Green to embrace the kinetic hilarity he utilized with Seth Rogen a few years back and McNairy plays his role as a functioning illiterate for easy giggles that aren’t earned. But even those additions are okay when you go full bore into the farce. The mistake is when you hope to also deliver a grand catharsis.

Bullock does her best to render the emotional turmoil authentic, but the script doesn’t do any favors by moving from laugh-out-loud to heartfelt soul-search. I like Clooney, but I think the change serves the film because of this tonal shifting. I can see him going too dramatic to render the jokes less impactful than Bullock. Yes she’s often depressed and ornery, but she does it with a nuance that retains introspection. Even as we smile at her throwing up from altitude sickness in the background, we see her brain working out the direction to pursue. And when she hits her stride to legitimately have fun, so did I. It’s too bad everything grinds to a halt for a tacked on message the satire should have revealed without the cloying melodrama.

Our Brand Is Crisis opens wide on Friday, October 30th.