The 1960s were a hotbed of activism by necessity. You had civil rights battles for racial and gender equality, protests standing in opposition of new wars coming down the pipeline after just finishing one that risked destroying everything, and America’s growing wealth disparity reaching an apex yet to be solved even today. You had an expanding populace surviving domestically in cities that were falling apart and in desperate need of resuscitation. Suddenly the “first world” hit a decision point on how to proceed forward into a modern age and those with the money and political influence to do exactly that in their own image stood tall to dictate terms. They spoke in abstracts and trends, adhered to bottom-lines, and completely ignored those they supposedly sought to help: us.

It’s therefore no surprise that the 2010s quickly became a decade molded after those days of civil unrest and the proactive attitudes used to ensure those speaking for the people were listening. As we see our government representatives calling their opposition names like “snowflakes” despite their own penchants to run and hide when forced into a corner for answers of which they have nothing but the admittance that they vote their financial interests rather than their constituents’ necessities, more and more citizens have realized the ship will not correct itself. So America has begun to congregate in the streets again as its voices rise online to combat a vile strain of anonymous, bigoted bile. It has mobilized in order to erase those errors years of complacency have wrought.

This is why a film such as Matt Tyrnauer‘s Citizen Jane: Battle for the City is so potent in 2017. While there’s the underlying notion of it telling us a captivating story from the annals of American history, it’s his depiction of the adversarial relationship between those making decisions and those affected by them that hits home. The idea that people educated in theory with the ego to deem themselves experts in a field they have never witnessed beyond the academic sphere should be in control has and always will be wrong. To fix problems broadly is often to miss the point of those problems. To view a “messy” city from above is to ignore the unique communal beauty to the chaos of life pumping through its veins.

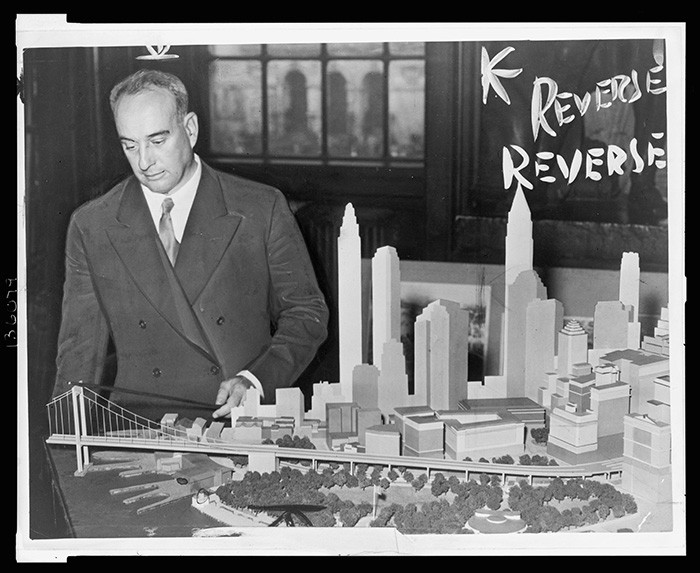

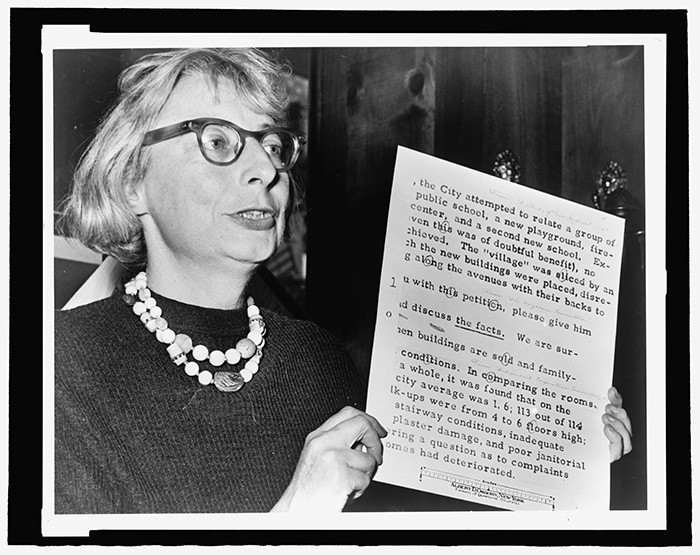

Where Robert Moses saw the capacity for more at cheap costs (solutions replacing problem areas with bigger problems his analytics and greed couldn’t comprehend), Jane Jacobs immediately saw the devastating destruction those “fixes” would deliver by acknowledging the people affected (herself included). All his degrees and money bestowed unearned superiority onto him, Moses’ power and clout operating with a utilitarian outlook benefiting his cronies in the present while punishing those unfortunately caught under his foot in the long term. She didn’t go to college, but she lived in the West Village. Rather than see definitions for “city” in books, Jacobs used her experience as a professional journalist to write a contemporary version of her own. Infrastructure can be immaculate, but it’s worthless if nobody’s there to use it.

She stood as a symbol of democracy against oppression like many are doing today. Moses dismissed her and her followers as housewives—my favorite part of this story since doing so made his image worse upon being defeated by those “who couldn’t ever defeat him.” This man was the czar in charge of housing projects and highways for years and yet every talking head Tyrnauer collects effusively lauds Jacobs as the singular luminary who truly understood the urban locale and could articulate it better than anyone else. When Moses and his peers blamed the people for not using their cement monstrosities correctly (blame never theirs), she rallied them to make sure he couldn’t ruin yet another neighborhood simply to line pockets while pushing the impoverished to the fringes.

Tyrnauer lets their fights (the two would lock ideological horns twice) unfold against a crash course in the topic of urban planning itself. We’re introduced to the Le Corbusier style, learn how it was bastardized and usurped, and begin to comprehend why this happened financially, politically, and socially. Relevant exposition is shared on behalf of both principle characters to reveal who they are, who they used to be, and what their respective goals became—mostly in their own words (Moses courtesy of archival media sources and Jacobs via interviews conducted before her death in 2006). There’s propaganda, public outcries, protest posters, and even examples of the obvious cyclical nature of time as we see today’s never inhabited cities of China awaiting people that may never arrive.

It doesn’t go too in-depth on the social ramifications of Moses’ tactics (those can be learned in countless other documentaries including one focused on James Baldwin—who delivers a brief soundbite here—entitled I Am Not Your Negro). One could argue it doesn’t quite paint Moses as more than a two-dimensional villain either (he pretty much is), but the film isn’t called Citizen Jane without reason. Tyrnauer is providing a forum for Jacobs’ side of this war against the people. He’s providing her voice so that we can remember her tenacity and drive to stop hubristic men in power from strong-arming the people into accepting opposition as a futile exercise. This is about very specifically spotlighting a woman demeaned, dismissed, and arrested by the patriarchy she ultimately defeated.

The fact we’re also educated on the topic—and don’t think urban planning has been solved when docs like Class Divide show little change in the half century since—only proves this film’s immense importance. There’s reason to question the social and intellectual elite, men and women who believe they know what’s best for others while abstaining from following the same rules. Jacobs saw what worked and didn’t. She spoke directly with those affected by Moses’ plans and pointed out his errors. At the end of the day it’s the people who rule America. The more you shove them down, displace them, and force them into corners, the louder and more impactful they will grow. To tear down our cities’ character and community for homogenization is to embrace dystopia.

Citizen Jane: Battle for the City is now in limited release.