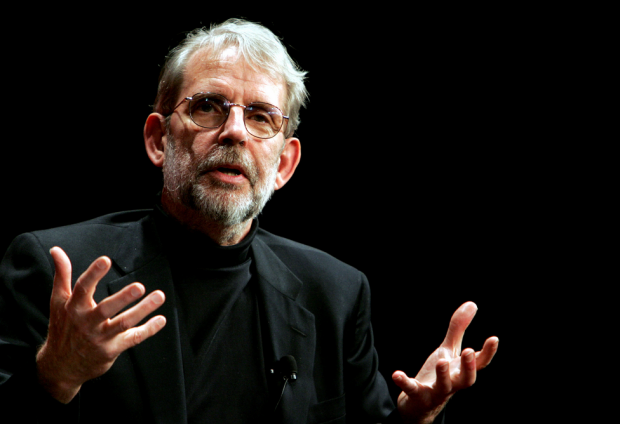

I’ve spoken to many people in my time, but few (if any) have the same credentials as Walter Murch, whose résumé would be amazing if it was only for the collaborations with Francis Ford Coppola: editing and / or audio work on all three Godfather films and The Conversation, truly groundbreaking sound design on Apocalypse Now, editing the terribly ignored Youth Without Youth and Tetro — even being around for the early days of The Rain People and lesser-seen oddities such as Captain EO. But that’s not the half of it, really, since he’s also been instrumental in proving how consumer-grade editing software can be as effective as high-end systems. And then there’s the work that helped George Lucas getting his career started. And the cult sensation that is his only directorial effort, Return to Oz. Or his book, In the Blink of an Eye, which is often considered the essential literary source on film editing. The list goes on.

We’re both in Bydgoszcz, Poland for the Camerimage International Film Festival, where he’s being handed their Special Award to Editor with Unique Visual Sensitivity. Given his credentials, you can understand why I took the opportunity to speak with him in spite of there not being a specific project on the table. Selfishly, I wanted to be able to pick his brain a bit, and, being as experienced as he is, Murch was able to satisfy that desire — even if he might be speaking about basics within his complex profession. For those without access to that world, however, some of this is truly surprising material.

Camerimage is giving you an award for “unique visual sensitivity,” which sounds fairly specific.

Meaning, for cinematographers, “Don’t ruin our shots!” [Laughs]

As an editor, do you have a personal view of “unique visual sensitivity”? Do those words resonate for you?

Yeah. I think it, on a very basic, practical level, is that — it’s “don’t ruin our shots.” But there’s a larger context to that, which is, “Take the material that we have shot and find the best way to shepherd this material through all the turbulence and rapids that both frequently happen to a film.” You can have a film that was shot with one intention and then, because of certain things over which we have no control, the final film is different than what the intention was. What an editor has to work with is that material, so it’s the film equivalent of how to transpose from one key to another and make it seem natural. That requires a certain visual sensitivity to that, and finding ways to rework the material, but within the spirit of how it was shot in the first place.

You’ve been around for so many changes in the industry, from the technology crafting films to how people assemble them. There’s this whole discussion about how the average shot length has been cut down from the ‘60s to today, so I wonder if that’s at all changed your relationship to images.

You know, I would dispute that concept. The average shot length of The Birth of a Nation, which was made 100 years ago, is five seconds, and Francis Coppola’s Tetro, which was shot six years ago, is five seconds. Action films, that is lower. On average, you can get down to, over the course of a whole film, three-and-a-half seconds per shot. But you can also compare two films shot within a year of each other: Sunset Boulevard, Billy Wilder’s film, and The Third Man. By today’s standards, Sunset Boulevard is slow in terms of its cutting pace; it doesn’t make it any less of a wonderful film. Third Man, however, which was shot, I think, the year before — anyway, both around 1948 — definitely looks like a film that was shot and put together today. It has that same kind of quickness of tempo. So I think it depends on the film and the sensibility of the director.

The quickest film ever shot, editorially, is Man with a Movie Camera, Dziga Vertov’s film, where he does one cut every frame, and he superimposes three strains at the same time. So you’re looking at just a blizzard of editing… not, obviously, throughout the whole film, but there are sections there where it’s inconceivable that a film could be cut quicker than that film, which was made in the late 1920s. I think if you look at certain kinds of television shows, like The Office, there, the pace has definitely picked up. I think, there, the average is a cut every two seconds or so. Basically every line of dialogue is a cut: duh-duh-duh-duh, cut; duh-duh-duh-duh, cut; duh-duh-duh-duh, cut; duh-duh-duh-duh, cut. If you compare that kind of a show with a similar show shot twenty years ago, thirty years ago, yeah, that has definitely accelerated.

The quickest film ever shot, editorially, is Man with a Movie Camera, Dziga Vertov’s film, where he does one cut every frame, and he superimposes three strains at the same time. So you’re looking at just a blizzard of editing… not, obviously, throughout the whole film, but there are sections there where it’s inconceivable that a film could be cut quicker than that film, which was made in the late 1920s. I think if you look at certain kinds of television shows, like The Office, there, the pace has definitely picked up. I think, there, the average is a cut every two seconds or so. Basically every line of dialogue is a cut: duh-duh-duh-duh, cut; duh-duh-duh-duh, cut; duh-duh-duh-duh, cut; duh-duh-duh-duh, cut. If you compare that kind of a show with a similar show shot twenty years ago, thirty years ago, yeah, that has definitely accelerated.

Can you think of ways that sensibilities have changed among directors, then? Has Coppola, for example, changed much from The Godfather Part II to Tetro?

Mmm… no, I don’t think so. Again, I think it’s down to the sensibility of the film itself rather than the filmmaker. I mean, Tetro was shot digitally, so individual takes were longer because you can just keep the camera rolling. He did a number of what are called “resets,” which is, from “action” you go along and then, at a certain point, you keep the camera rolling and just say, “Just go back a couple of lines and pick it up from there.” So, in a sense, you’re kind of cross-country skiing your way through the shot, and that requires a different approach on our end, editorially, to dealing with the material. But the end result, I think, is not profoundly different. It’s down more to the sensibility of each individual film.

When you’re in that sort of situation, with a new system — cross-country skiing, as you call it — has your accumulated experience prepared you for that new sort of experience? Do you have those moments of concern, or is it more a challenge you embrace?

Yeah, no, you have to figure out how to simply keep track of all that stuff. Tomorrowland also had a great number of resets in it, and, there, you’re just dealing with a take which could be half an hour long with 30 resets in it, and the technology now, in 2015, has caught up with that. But, at the time that we shot — which was only two years ago — it hadn’t yet, so we had to evolve a pretty complicated way, editorially, of marking all of those resets — to make sure that we were “tabulating” them, so to speak. But I’m using a new editing system on a film I’m cutting in London; I’m using Adobe’s Premiere for the first time. So I’m always ripe for a new challenge.

What’s changed in the two years, then? Is it just a system update that accommodates resets?

Yeah. I edited Tomorrowland on the Avid. The film before that, Particle Fever, I edited on Final Cut Pro 7, Apple’s system, and the documentary I’m editing now in London, I’m using Premiere. So in the space of three years I’ve used three different editing systems. That’s kind of the world we find ourselves in now; it may settle down. I hope Avid survives. Its stock price has gone down again, and they’re flirting with bankruptcy frequently. I hope they can survive, because we need as many different systems as we can have. Technically, the reset issue now… if we we’re making a film now that had resets in it, there is a kind of a silent buzzer that, during the take, you give this control either to the script supervisor or to the cameraman, the assistant camera. When the director interrupts a take and says, “Just go back,” we go, “Enn!” There’s a little buzzer that says, “This is a reset.”

I mean, these are kind of basic, fairly simple technologies, but the way that digital is being used has occasionally outraced the technology that can support it, and this is a good example of that. The danger of resets, for an actor, is that it interrupts the trapeze act of every take. The talented actor who launches himself into a take the way a trapeze artist launched themselves into a routine, where you’re handing off from one actor to another, and it’s a very complicated aerial ballet, in a sense, and for the director to interrupt that — “Stop!” — is like freezing a trapeze act in mid-air. The actors say, “I think I know where I am, and you want me to back to that handheld? Okay, I think I can get back there.” But it’s an invisible, very demanding discipline to do that to actors, and I, in general, [Laughs] would recommend doing that as little as possible, because I think the nature of acting really demands it.

Speaking of invisible disciplines: do you have, even in minuscule ways, have different mindsets between Adobe, Final Cut, and Avid?

The equivalent would be… I mean, they’re not profound, profound differences. The equivalent would be a concert pianist saying, “We couldn’t get the Steinway, so you’re going to have to play the Yamaha,” and you have to recalibrate certain things between those. But they’re not profound differences; they’re like dialects of a language. You have to say, “All right, I’m going to speak with a Bronx accent now,” or, “Now it’s a Brooklyn accent.” So you make certain modifications. Avid, for instance — unless something has changed recently — can only give you twenty-five soundtracks at the same time, whereas Adobe can give you many times that. So you adjust to move from Final Cut 7, which also gives you 99 soundtracks. I had to readjust how I worked to compress things into the 25 tracks.

Have you been particularly impressed by recent examples of editing or sound design?

You know, when I’m working on a film, I don’t see many other films — so I can’t give you a real answer to that, I’m afraid.

What’s the exact purpose behind avoiding other films? Keeping your mind clear of other possible approaches?

Yeah. Just the hours we put in are so long, and you have to balance a kind of mental house of cards to work on a film. That takes time to set up. The first three weeks of working on a film, you’re really kind of doing that, getting into position to work on a film. Seeing another film — again, this is just me — in the middle of that tends to put that house of cards in jeopardy.