Stop-motion can often be a painstakingly laborious, detailed process, so the more hands the better. This fact was not lost on Laika, who, along with hundreds of employees, brought on a pair of directors to undertake their latest film, The Boxtrolls. Anthony Stacchi and Graham Annable, who have various experience in many forms of animation, were the leading creative forces behind the project and we got a chance to speak with the pair.

We discusses how they split up duties, a pair of excellent supporting characters, what sets their method apart in the realm of animation, being compared to minions, screening films for their voice-cast, recent favorite animations, working from a storyboard, their most complex scene, and more. Check out the full conversation below and make sure to read my chat with Laika CEO Travis Knight here.

The Film Stage: I know you storyboarded and developed the story together, but when it comes to the animation process, how do you split up your duties?

Graham Annable: Well, yeah, we’re sort of joined at the hip for all the pre-production and story side of it, but once the animation schedule starts that’s where the advantage of having two directors really shows up. So Tony and I always start the day with heavy conversation and going over all the shots that are going to be up for the day. Then we ultimately split into two separate edit suites to keep everything flowing as efficiently as possibly and sort of maximize how many animators can get information from the directors. But all day long we’re continuously checking in with each other.

I loved the henchmen, even some off-screen dialogue remarks they had. I’m curious how much of that was from the book or where they expanded at all? Richard Ayoade and Nick Frost are perfect.

Anthony Stacchi: They are sort of inspired by some of the men in Red Hats or some of Snatcher’s men that are in the book, but they are not based on any particular guys. They are a bit of a conglomerate of all those guys that are in the books. Almost all of their lines are written, but those guys will take a line and then riff on it, different ways of performing it or adding to it. It’s particularly whenever they are having a conversation back and forth, that’s when they would improvise stuff that we would use. It’s a little easy. The scene when they are off-screen, when Snatcher’s face is getting distorted by the cheese, a lot of lines we had storyboarded, but we wanted to keep alive their conversation that was happening in the background while Eggs is sneaking around, so we had a lot of alternate ideas that they could say for that too and then we just had tons to play with once we got in there in the editing.

Annable: Yeah, and in some of the early iterations of the script, Trout and Pickles weren’t as featured or had as big a role to play in the film, but after the first couple of recording sessions, it became obvious to Tony and I that we needed to…

Stacchi: …give a little more screentime to these guys. They were so entertaining and they added so much more to the film.

I won’t spoil the end, but this film definitely shows the dedication and patience required for stop-motion. You guys have both worked in different forms of animation. What sets stop-motion apart and why should it still be considered a form to use?

Annable: Well, I think stop-motion inherently gives our films a really unique look. There’s something in this day and age where CG imagery has gotten to such a level that I don’t think films can get any bigger or louder for spectacle any more. It’s just gotten to a point where it’s so well done and as audience we all kind of feel like we’ve seen it before at this point. Yet, here is stop-motion still existing out there and we’re still making films that way, but suddenly it’s becoming a very unique and different feel. I don’t think audiences necessarily know why, but they can feel it when they watch our films that it’s different and it’s offering a new perspective.

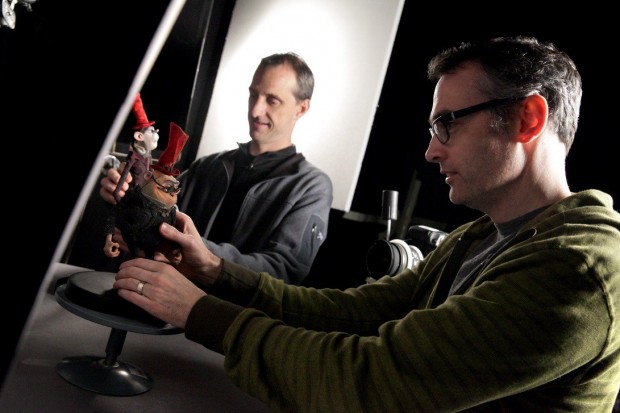

Stacchi: Yeah, and I feel like that stop-motion inherently has this tactile quality where you just want to reach out and grab it. It harkens back to your memory as a child of playing with a doll or playing with a little soldier or a model train set. I think everybody has those memories, whether they are deep in their head, and there’s something about the miniature quality and the tactile that sets it apart from all of the slicker, colder, plastic CG stuff.

I heard it took a bit of time to figure out the look of the characters. For the Boxtrolls, they reminded me of minions with much grander personality and just more distinct. Did they start out more generic?

Annable: It’s funny. We were in the process of making the movie when the first Despicable Me came out and we were like, “Oh, no.” [All laugh.] People are going to think these are our Boxtroll minions. No, from the very beginning we knew the core of the story inspired by Alan Snow‘s book was the story of this boy that had been raised underground by Boxtrolls and around him had risen this surrogate family. So we always knew that we wanted to have the best potential Boxtroll parents for Eggs and so a pairing of the gruff, kleptomaniac Shoe, with the more responsible and tended Fish was a nice pairing to sort of orbit around Eggs. Then it was just coming up with individual personality traits, kind of like the Seven Dwarfs for the rest of the Boxtrolls because we knew they would get a limited amount of screentime so you needed to get who they were rather quickly. I always grew up with Gremlins and that factored into some of the ideas in the films.

Stacchi: Basically, in my head, as a kid I found a baby raccoon after his mother got ran over by a car, so I had this pet raccoon and I had this really great husky that the raccoon thought it was is mother, so that’s basically Fish and Shoe in my mind.

I was also reading you screened a few films to get your voice cast inspired. Kes was one, which is one of my all-time favorites.

Stacchi: Yes! Kes. I’ve always loved Kes. We watched it as a story department. There’s something about these lost boys, specifically the character of Eggs, whose name is Arthur in the book, and then these Boxtrolls, which are kind of like the lost boys in Peter Pan. And I loved that boy in Kes. I loved the way he looked. I wanted to use him as inspiration for the way Eggs looked. Luckily, Isaac Hempstead-Wright [the voice of Eggs] actually looks like that boy in Kes, but that came much later. Yeah, I’ve always loved that movie and when I started this project my son had just been born, so the story really resonated about this orphan boy and the absentee father and the surrogate families and stuff he grew up around.

Annable: David Lean‘s Olivier Twist was a film Tony referenced a lot. For me, when I came on the project, I felt like a lot of what was being created in the world was akin to Delicatessen and City of Lost Children, the Marc Caro and Jean-Pierre Jeunet films. Those were definite influences.

When you are filming more of the fast-paced scenes, do they have to be 100% from the storyboard or is the room for a little adjustment?

Stacchi: Yes, that one monumental shot when Fish first comes down into the cavern it evolved through every step of the way. It existed in a certain form in board, representing that it would be a big shot and it involves a lot of difficult drawing, but you could still not really, truly get a sense of how the camera could move through that space. It got handed on to the pre-vis department who then began to get a much more articulated version of how much of the set we were going to require and how the general movement of the camera would really work. Then it goes even further when the actual set exists and everything is truly all there it involves another step as we sort of begin to iterate through it.

Annable: It was an interesting process for me because the Boxtroll cavern is quite large. It’s a pretty huge space that we built. For the beginning part of the shooting schedule it was always in fragments, it was always in pieces. We were shooting smaller shots with one or two characters in them and as the schedule progressed, towards the end, like Voltron, we were able to bring all the pieces of the Boxtroll cavern together to be the one big massive set for the massive shot at the end.

During this long production, did you get a chance to seek out any other animations? Perhaps The Wind Rises?

Stacchi: No, you know it’s funny. The Wind Rises got such a limited release here. I really wanted to see it in the theater and then I missed it. I still haven’t been able to see it, but I’m a huge Miyazaki fan. You know, we were working a lot. [Laughs.] I get to see all the big studio releases because I have an eight-year-old son. So I’m always amazed at the last couple, How to Train Your Dragon, Kung Fu Panda, and stuff. I love those films, it’s just amazing how far they’ve come, and Brave and stuff. But, yeah, I just saw Snowpiercer the other day and I was like, “Now I remember what it’s like to go to a movie theater and see a movie and just really relax and love it, because it had been about 18 months.”

Annable: Yeah, it’s been a rarity as of late.

Yeah, I would definitely recommend The Wind Rises. Last question, the ballroom sequence is a fantastic scene in the movie and it seems like the most elaborate. Can you talk about the technical approach to that scene.

Annable: Honestly, Tony and I as directors didn’t really know what we were asking the studio for what was going to be such a huge undertaking. We had sequences where we had a giant mecha-drill destroying the town of Cheesebrige with smoke and fire and everything else and we thought those would be the most elaborate. Nobody even barely blinked. They all knew how to handle that stuff. But when we proposed that dance sequence, the waltz in the ballroom, 40-odd puppets, everybody just stopped in their tracks. It was suddenly this impossible task. It took all 18 months of our shooting schedule to basically produce a little under two minutes of footage. Our strongest storyboard artist had to storyboard it out. Our great composer, Dario Marianelli, had to write a waltz for us. We hired two of the choreographers from the Portland ballet to come and choreograph the whole waltz so we could shoot it from every angle for this great stop-motion animator. Then we to had to build the set in some way that it could be broken apart so he could get access to these dancing couples. Once that was done, our CG department had to come and add a lot of CG extras in the background as well as to put all these characters, the practical stop-motion animated ones and the CG ones, into that ballroom with the camera swirling 360 degrees, so it was huge.

The Boxtrolls is now in wide release.