Note: Spoilers for Gone Girl and David Fincher‘s other films below.

“The sooner you look like yourself, the sooner you will feel like yourself.” People tell a lot of lies in Gone Girl, but perhaps none as big as that one. This is a film in which appearances and images of everything, from the big picture to the tiniest details, cannot be trusted.

In a way, then, Gone Girl is the film that Fincher has been working toward his entire career, placing the distrust of appearances of his early films and the shortcomings of images in his later work together in a way that projects its distrust directly onto the viewer. The Game puts a banker (Michael Douglas) into a staged alternate-reality that culminates in his inability to differentiate it from reality. Fight Club’s protagonists assert that society’s consumerist obsessions are turning us into commodities, only to reveal that the nameless narrator is himself not who we thought.

Fincher’s more recent and sophisticated films tend to ask these questions in less abstract and grandiose ways, looking at information and images rather than large statements about consumerism. Zodiac is a fight between analog and digital and ultimately the primacy of the former and the versatility of the latter. Characters are clumsily stuck trying to solve a killer’s riddles and Robert Graysmith (Jake Gyllenhaal) sees his efforts slowed as he digs through archives of information and scammers to meet contacts in person. All this is suggested by Fincher’s choice to shoot the film digitally—the blood, the city, and the information that creates its own plane on the image all show that digital technology is just as “real” and ultimately more versatile than clumsy analog partners. The Social Network approached it from the other direction, starting with faith in the digital image but gradually coming to doubt it. At the start, Mark Zuckerberg (Jesse Eisenberg) loses (or rather throws away) Erica and is not tagged for Harvard’s prestigious final clubs. His reaction is to create Facebook, a digital projection of oneself at their greatest—the photos of parties, a clear marker of relationships, quadruple digit friend counts—so as to hide their own inadequacies. It ultimately fails Mark—even his digital self is lonely without Erica, and has he sits refreshing the page as the film draws to a close, the takeaway is that there are some lies that we can’t even get away with on the digital landscape.

Gone Girl goes furthest: whether it is one’s physical appearance, their demeanor, or their presentation on the news, one cannot trust what they see. Moreover, the film itself continues to reveal its own deceptions, and the cinematic image itself becomes fallible, subject to issues of timing and context that obscure the truth. Fincher’s films have struggled with how our reality — be it self-imposed or not — shapes us, and in Gone Girl they shape not just the characters, but the viewers. We unwittingly become just like the masses in the film rushing to cable news day after day. Like them, we don’t even know how crooked our vision is.

Gone Girl goes furthest: whether it is one’s physical appearance, their demeanor, or their presentation on the news, one cannot trust what they see. Moreover, the film itself continues to reveal its own deceptions, and the cinematic image itself becomes fallible, subject to issues of timing and context that obscure the truth. Fincher’s films have struggled with how our reality — be it self-imposed or not — shapes us, and in Gone Girl they shape not just the characters, but the viewers. We unwittingly become just like the masses in the film rushing to cable news day after day. Like them, we don’t even know how crooked our vision is.

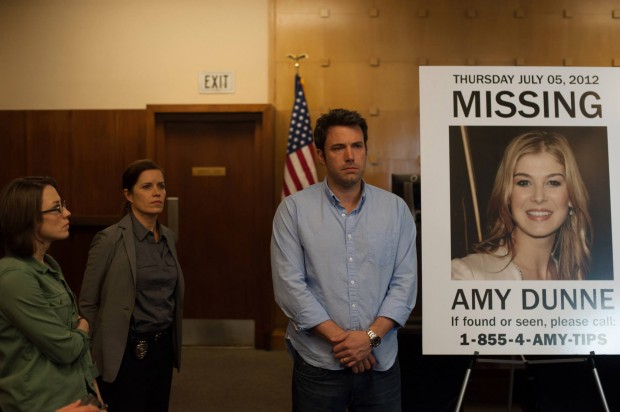

The general synopsis is itself a case of deceptive appearances. Nick (Ben Affleck) returns home to find that his wife Amy (Rosamund Pike) has disappeared. The case is initially declared a kidnapping because of the scene at Nick and Amy’s home: an overturned table and broken glass indicates a struggle, and as the lead detective will tell Nick later, no blood and no body means kidnapping—look at people outside the house—but blood and no body means murder—look at people inside the house. Save for a small bit of blood up high, there is not anything to suggest murder, or so it appears. A closer look with technology reveals something the human eye cannot—a great deal of blood all over the kitchen floor. With that, they start to look inside the home, and Nick is accused of murder.

So which is it, victim or murderer? Nick is never quite who he seems to be. We are introduced to him by his concern for Amy and, in flashbacks, his self-aware smooth-talking that endears him to his future wife. Once Amy is missing, however, we see how oblivious, if not uncaring, Nick is. He doesn’t know Amy’s blood type, what she does all day, or who her friends are, and flashbacks also tell us that he was irresponsible and a bit selfish in the past. Before we know it, new information tells us that he’s an abuser and a cheat, and then he even looks to be a murderer. Key word: Looks. Nick is only a murderer until we learn that Amy is alive. Nick is now a victim not in the sense that it is his wife that is missing — he didn’t care much for her anyway — but in the sense that he is not the man TV keeps accusing him of being.

With Nick constantly being cast in a new role in this tabloid drama — and what is cable news if not a tabloid? — we slowly learn that Amy is just the opposite. Nick is powerless: he does not know where Amy is or how to prove his innocence and the media controls his image. Amy, conversely, can manipulate her own appearance. When we first hear about her when Nick is being questioned, she sounds like a stereotypically subservient housewife. He goes to work while she stays at home reading. She uses this illusion to cook up her plot, one which will see her vanish and him executed for her murder. When we see where she disappears to, she dons a disguise, reinventing herself as Nancy, who has walked away from her cheating boyfriend in New Orleans. She plays the vamp with Desi (Neil Patrick Harris), and returns to Nick as the traumatized victim. Throughout the film, then, Amy puts on appearance after appearance, shaping the way people—particularly men, as the one person to see through it is a woman—perceive her and then undercutting their assumptions when necessary. In doing so, she casts Nick in various roles: her initial plot makes him look like a murderer while her reappearance makes him look like a grateful and dedicated husband. Neither, of course, is true.

So while the plot is itself about how misleading appearances are, the film manifests this idea in a broader distrust of images in general, the cinematic image included. With it revealed to the audience that Nick was unhappy with Amy and much prefers time with his mistress that he may soon be allowed, he puts on a “Find Amy” pin. Against Nick’s wishes, a woman helping out with the search for Amy takes a selfie with him, and that photo ends up on cable news. How could a man whose wife just went missing be posing for photos with other women? Maybe he killed her. So the rumblings begin.

Who did he kill, though? Amy is famous not for being a missing person, but because she is the inspiration for and daughter of the author of the best-selling “Amazing Amy” book series. But “Amazing Amy” had a very different life than Amy did. Amazing Amy played the cello, was a varsity volleyball player, and had a dog to “make her more relatable.” Amy quit cello at age 10, did not make the volleyball team, and didn’t have a dog, or even a particularly happy childhood. As Nick remarks, her parents were not the best. Yet it is this false image of Amy that is sold to the media and the public and that turns her disappearance into such a sensation. We have to ask: Is the public upset about the disappearance of a person—Amy herself—or about the disappearance of “Amazing Amy,” her imageable counterpart?

The cameras, too, are not to be trusted. Nick reflexively, and only momentarily, smiles while posing next to a poster soliciting information on Amy’s disappearance. Amy finds herself in a house with plenty of closed-circuit cameras, and she performs for one in a rather shocking manner for the sake of her story. They lie, and nobody realizes. Mediated images are already suspiciously shy of reality.

Nowhere is this more apparent than on TV, which tells not a single truth throughout the film. We know that Nick did not consent to that photo. When public opinion turns against him, they presume him guilty and her dead—both false. Nick wins Amy back with a spectacular — and spectacularly performative — television interview. It goes without saying that words cannot be trusted — everyone tells lies to save their own skin—but images are even more dangerous.

That danger extends far beyond the world of the film, manifesting itself, thanks to the film’s ambitious structure, in manipulation of the viewer. It is here worth noting that nearly all of Fincher’s previous films have progressed chronologically, with The Social Network being the sole exception, but even it merely splits into two timelines and tells both chronologically. Thanks to Gillian Flynn’s script, adapted from her own novel, Gone Girl parallel edits and loops back on itself. By interweaving flashbacks narrated by Amy from her diary with the first few days of the disappearance, the unreliability of the cinematic image becomes part and parcel to Gone Girl. As it so often does, the voice-over conjures images. We see Nick and Amy’s meeting, their happiest days, their struggle through tough times, and his descent into abuse. While these images start true, at a certain point, unbeknownst to us, become false, revealing themselves to be so only after our view of Nick has been colored. While we may not go so far as to say that he’s a killer, we do believe that he was abusive. The reveal transforms Amy, in story terms, from victim to antagonist. But, because the film is inflected with Amy’ subjectivity throughout in the form of voice-over, our sympathies stay with her. After a few days of watching Nick — who does not have a voiceover — we learn the truth when it jumps back to “One day gone” from Amy’s point of view: If this had been reversed we would have a radically different film on our hands.

Gone Girl is not strictly about marriage, as it may appear on the surface, or even about the way an anxious public feels the need to cast heroes and villains in more complex stories, but about how the manner, the order, the vehicles, and the timing at which information is given to us affects our processing of it. The damning flashbacks of Nick coincide with amped up suspicion and the discovery that he has been cheating on Amy — put them a little earlier or a little later, and we probably would not have believed them, but where they are, they convince us, and they heighten our alliance to Amy as a result. Most impressive is a similar effect in the scene with one of Amy’s exes in New York. Early in the film, Amy’s parents say that she attracts stalkers and admirers, and they point to two exes — Neil Patrick Harris’ Desi, and another, Tommy (Scott McNairy), who has little screen time. Nick goes to meet Tommy when our sympathy for Amy is at its lowest, so when he says that he did not rape her, we believe him. Looking at this event holistically, in context of all the lies and deceptions in the film, do we really want to take his word for it? It takes us nearly 150 minutes of watching and hearing about Amy and Nick to decide who they are. How are we going to take someone at their word after 5 minutes? Certainly the film’s self-conscious structure, one that begins following two separate timelines but allows one to dissolve into fiction, then loops back and cross cuts once again, all while presenting one character’s story subjectively and the other objectively, is fully aware of the importance of how timing colors perception, and the structure and the story itself tell us to consider timing and context and to take what we see with a grain of salt. If we began with Amy and saw her accrue sympathy while Nick was painted as the bad guy, we would certainly not believe Tommy.

Fincher’s films have long been “pulpy” and “trashy,” from the grotesque serial-killings of Seven to the brutal nihilism and sexual violence of The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo, and as Fincher’s career progressed he has gotten better at presenting his own concerns in spite of this material—in short, he’s increasingly exemplified Andrew Sarris’ brand of “auteur theory.” With Gone Girl, Fincher works not in spite of but through the pulp: its mysteries and twists allow Fincher to take his concerns further than ever. One could argue that makes Gone Girl more Flynn than Fincher, but the self-referential nature the film takes on also allows it to pose much bigger questions than its predecessors.