There are at least two problems with the phrase “self-discovery”: a) the idea that discovering the self is a discrete act; b) the idea that the self is a discrete thing. In case you haven’t noticed yet, I’m probably not the target audience for Wild, Jean-Marc Vallée’s adaptation of Cheryl Strayed’s best-selling memoir of her 1,000-mile trek through the Pacific Crest Trail, a journey of… you guessed it. But Vallée takes what could have been an insufferably hokey stream-of-consciousness, downplays the hokey, and pushes the stream. Vallée distills the memories defining Cheryl’s journey to brief, delicately composed flashes—moments where little ostensibly happens, charged with tension, each as important as the last.

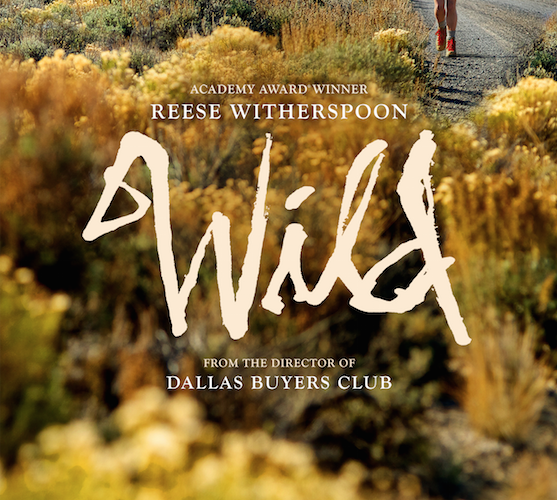

As Cheryl, Reese Witherspoon gives a performance that bristles with commitment and underplays the character’s wellspring of anguish. Cheryl is less of a character per se than Matthew McConaughey’s Jon Woodroof in Vallée’s Dallas Buyers Club, and it’s telling that she irrationally saves a condom and a Flannery O’Connor book from discarded memorabilia: a moderate sex drive and brutal, yet pious literature somehow precisely target Fox Searchlight’s demographic. But Wild has less in common with Club than Vallée’s 2011 film, Café de Flore, grounding intense emotion in low-key observation, here embodied in Cheryl’s journals and resentful, yet tender letters to her ex-husband. It’s anchored on the physicality of Witherspoon’s performance, coupled with her reminisces: reflections, irony, or comical overstatement be damned, the act of putting her pack on is a physical achievement before it is anything else. A less flashy supporting performance by Laura Dern as Cheryl’s ailing mother deserves just as much acclaim; the way Dern readily swallows a young Cheryl’s claim that she’s “more sophisticated” than her mother accurately cuts to the bone.

Vallée and his actors can’t fully strip Wild of clichés. We don’t need to see a heroin den straight out of a PSA for Cheryl’s drug-addled past to surface; we don’t need to see her joyously howl like a wolf in the night, on account of that scene has already played in the collective unconscious’s imagined version of this movie infinity times; we certainly don’t need shameless tie-ins with Snapple and REI to punctuate Cheryl’s journey. Fellow hiker Greg (Kevin Rankin) seems to exist solely to validate Cheryl by negative example, and the less said about her encounter with a reporter from the Hobo Times, the better.

In other ways, the film defies expectations. Cheryl’s gender is important without being her sole defining characteristic. An early vulnerable encounter with a stranger offers a credible, low-key mixture of threatening and hospitable signals. Vallée is gifted enough with actors to make the man convincingly complex, hinging on the key line, “I don’t blame you.” Elsewhere, Vallée overplays the creep factor in the form of two hunters, but skillfully guides Cheryl’s reaction from quiet to explosive.

More often than not, the film tosses off its heaviest material, be it the cycles of abuse permeating Cheryl’s girlhood household, which are illustrated through absence, or Cheryl’s life as an addict, pleasingly out of sync with the hike. A claim to “[saying] yes instead of no” accompanies one of Cheryl’s darkest memories, but it just as aptly defines her persistence, and that is the film’s saving grace: an attempt to meld trauma and triumph into a coherent whole. And it helps to be partial to Simon & Garfunkel’s “El Condor Pasa (If I Could),” but I enjoyed the way music flits in and out of Cheryl’s narration, further layering the dynamic between past- and present-tense. The film’s final evocation of a future never witnessed beautifully aligns with its playful fusion of past and present.

Wild premiered at TIFF and opens on December 5th. See our complete coverage below.