It may only be his second feature-length fictional narrative, but writer/director Guy Édoin‘s Ville-Marie is something special. The title is named after the Montreal hospital where the majority of the film takes place and from an unforgettable opening that violently shakes us awake to prepare for the sprawling yet meticulously constructed plot extending out of its devastation, Édoin and cowriter Jean-Simon DesRochers grab us with a disorienting amount of seemingly disparate avenues. Two automobile accidents will give each character a reason to despair and then to rediscover hope—tragedy breeding melodrama and long cloaked truth.

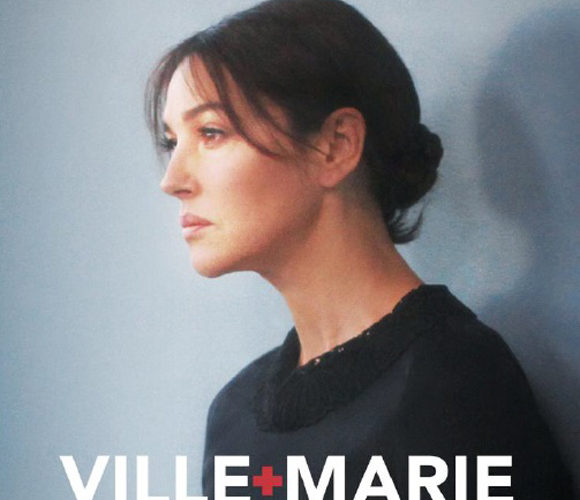

Young Thomas (Aliocha Schneider) is the unwitting witness to the first emotionally crippling bit of carnage on the day his actress mother Sophie (Monica Bellucci) returns from a three-year work-related sojourn. Pierre (Patrick Hivon) is the EMT on the scene desperately trying to keep the victim alive while his partner avoids myriad construction zones blocking them from the hospital and Marie (Pascale Bussières) is shown to be the night nurse awaiting their arrival. They are four people—two somewhat estranged pairs who have never truly opened up to one another—about to begin existential journeys towards answers they’ve avoided their entire lives.

Each one is haunted by the past. Thomas yearns for an identity beyond the one his mother has projected upon him in a reality that might be less real than the ones she plays in front of the camera. Sophie seeks to keep truth buried within her despite asking ex-boyfriend and current director Robert (Frédéric Gilles) to write their latest collaboration as an autobiographical account of her tragic youth. Pierre cannot shake the survivor’s guilt he’s brought back with him from the military and Marie the same but from a place of domesticity that may rip her conscience apart even more. And here they all are facing mortality, too afraid to lay bare their fears with the other.

Édoin ensures we cannot escape it, calling on cinematographer Serge Desrosiers to capture intricate compositions in high-definition close-up to temper the more conventional set-ups of conversation and drama. They supply a calming effect against the chaos surrounding them, brief transitional reprieves to gain our breath before the focal point changes and we walk in the next character’s shoes. Each of the four paths contain more substance than probably necessary, but the tiniest details aren’t lost on us to understand exactly what’s felt. Each is a self-hating emotional recluse, quick to verbally spar with claws bared than to admit they are just as broken as everyone else.

I loved the elaborate construction keeping us on our toes from one weighty step to the next. Sex, drugs, and alcohol numb them all, cutting short their turn until clarity can return. And the wholesale change of aesthetic when playing scenes from Sophie’s latest film in glorious soap opera-y plasticity is both jarring and welcome in separating its combination of flashback and fiction from the otherwise authentic on-the-ground kinetic footage. It’s inclusion also enhances the sense of artifice tinting each movement—no matter how subtle or unconscious. We see them vulnerable, but not fully naked until each hits his/her respective rock bottom. And you can bet that they will.

You may reject conveniences the story takes to place its pieces in carefully thought out positions for its crisscrossing of lives, but I wholeheartedly believe it works in the context of the film’s tone. The drama is so heavy that we need a bit of rigidity to balance against the emotion. Each contrivance is catered to its respective subject to assist in parsing their lives with the whole. Sophie’s life is so harrowing that soap convention lessens its overwrought descent. Pierre’s PTSD is too serious and timely to be treated with cartoonish flashbacks, so Édoin hit us aurally with nightmarish sounds juxtaposed against his psychological self-alienation.

The acting helps cut the script’s cynical nature too by remaining naturalistic no matter the circumstance. Bellucci is perfect as the glamorous celebrity out of her element being a mom and Schneider the right mix of angry, lost, and acutely empathetic if only to reveal his internal struggle. The real revelations for me, though, were Hivon and Bussières. We see the pain in their eyes from the beginning—a pain that never disappears until their very last scene. And even then it’s still in the background, momentarily relieved but far from forgotten. This quartet might travel through the wringer, but each comes out better. It will just take a bit longer to realize.

Ville-Marie premiered at TIFF. See the trailer here and our complete coverage below.