On first blush, Wi Ding Ho’s Taipei-set Terrorizers looks like a love story six years in the making. That’s when young, blonde dishwasher Xiao Zhang (J.C. Lin) gave roses to a pretty girl named Yu Fang (Moon Lee). Now he’s returned from sailing abroad as a chef, reconnecting with his uncle for breakfast before starting his new job at a local restaurant. She just so happens to be working at the diner they visit. While Xiao knows exactly who she, Yu Fang does not—maybe because his hair is black now, maybe for different reasons. He doesn’t give up, though. He sees her again, jogs her memory, and soon they’re together.

They talk about their future and always being there when the other needs them most. This is crucial for Yu Fang, who feels like everyone who ever loved her left: her mother disappeared when she was a child, her father is currently in the process of doing the same by marrying his pregnant secretary and moving to further his political career. Yu refuses his invitation to join. This city is home and she’d inevitably feel abandoned either way. As Xiao talks about moving in with each other, however, she still can’t help being skeptical despite his obvious devotion. So when tragedy strikes in the form of a violent, sword-slashing incident at the train station, he proves his unwavering love by sacrificing himself to save her.

It’s a story that usually fills up a film’s entire runtime with romance, suspense, and melancholic climax satisfying all viewers. Yet it’s only the first 20-or-so minutes of Terrorizers. It’s chapter one. There are three to go and a trio of characters we’ve yet to fully meet: Ming Liang, Monica, and Kiki. Ho and Sung use them to dive deeper into that opening act to reveal how nothing was quite as it seemed. Some scenes were truncated, others omitted completely. Some events were set-up for us to presume one thing despite proving something vastly different. The filmmakers ostensibly chopped up their plot to manipulate their courtship before rewinding to fill in the blanks.

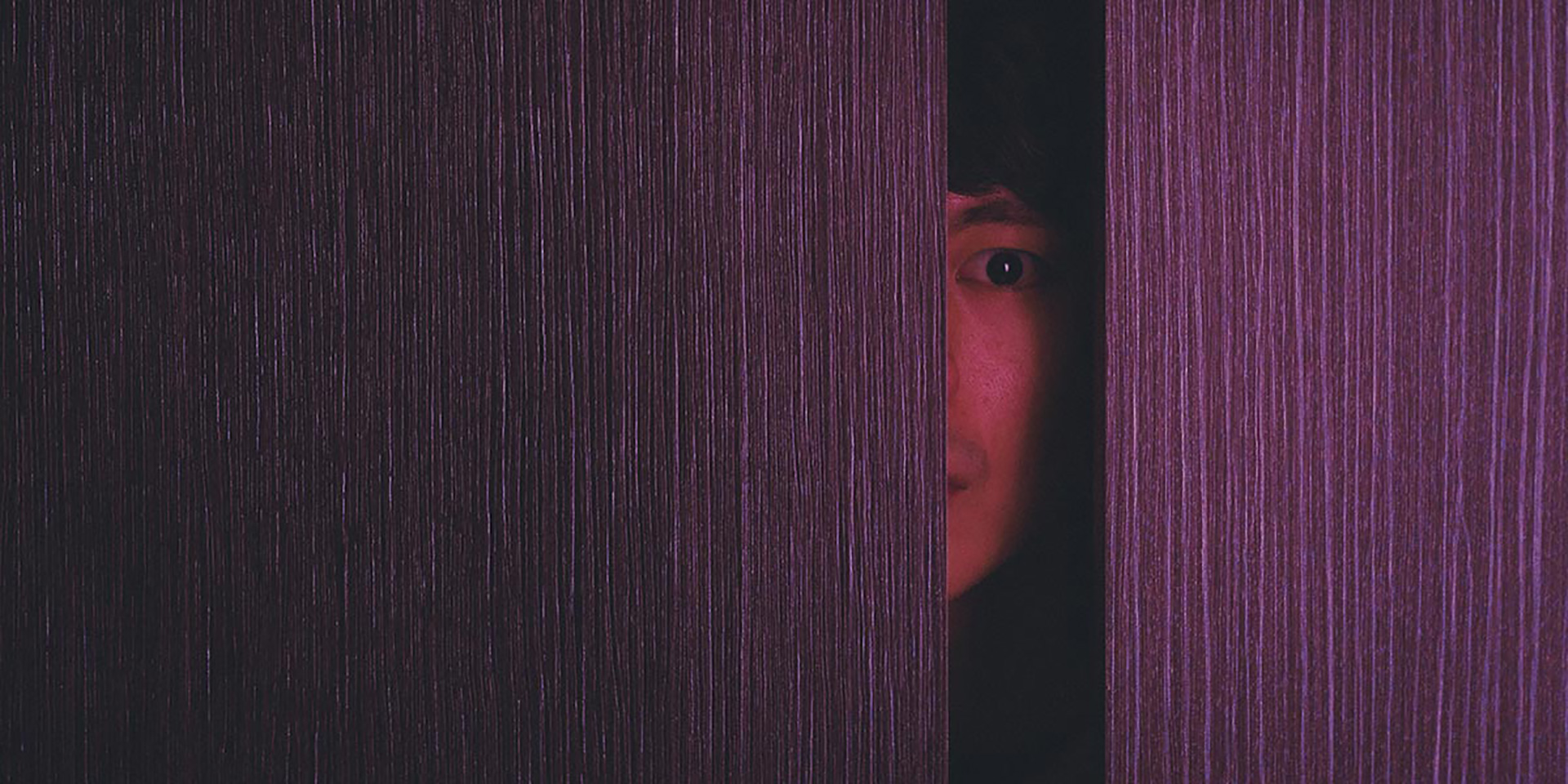

That’s not to say the romance isn’t real. Just because the progression of Yu and Xiao’s love was excised from the complexity of the world surrounding them doesn’t mean they didn’t fall for each other exactly how we’re shown. The difference lies in context. It lies in meeting Ming Liang: the son of Yu Fang’s father’s political benefactor and their roommate with whom she barely speaks. He’s under the sociopathic idea that she’s his girlfriend regardless. Living in a virtual world of videogames and a charmed life of getting what he wants (courtesy Dad’s money) has him losing grip on reality. And that’s before catching a glimpse of Monica while spying on Yu. The women share the same acting troupe, but he recognizes her from elsewhere.

Monica, focus of chapter two, was a viral sensation from a porn video her ex-boyfriend produced and can’t shake that past while trying to become a “real” actor. Ming falls for her even though they’ve never met. The stalking gets more intense, his brazenness growing darker with every new twist and turn in her tumultuous life. What he sees ultimately refocuses the timeline of Yu’s prior chapter before both receive more clarity through the next. While chapter three is Ming’s, it really exists to introduce Kiki as more than the waitress daughter of Xiao’s bosses: she’s a teenage cosplayer who likes Ming and knows how to use her looks and flirtations to influence men that adore her. The lust connections keep multiplying.

So do the horrors of what’s happening—just not as you might expect. For one: Ming Liang is a bad dude. He’s a creeper with violent tendencies who doesn’t appreciate privacy as a concept. And yet, through Kiki and a supporting player in Lady Hsiao’s masseuse, Ho and Sung appear to want us to sympathize with him. It’s a bit worrisome at first; knowing what we know about where his character is heading (per chapter one), supplying him any benefit of the doubt is impossible. If he does something nice it’s not seen as altruistic to us, even if it does to those he helps. We consider him a monster unworthy of trust and the filmmakers capitalize by turning perception into the real enemy.

They use Ming Liang both as a voyeur into Yu Fang and Monica’s private lives and irrefutable evidence of a failed system of accountability that spans legal and media fronts. More than the means to manipulate law enforcement with financial connections, he can also shape the press’ narrative by simply existing as a man in a patriarchal society. Just as the opening feels like a fairy-tale love story, his role within it plays like an archvillain no one could ever see as anything but a criminal who deserves to be locked up for the rest of his life. What he knows (and what he’s shown us), however, has the potential of swaying public opinion to his side.

Terrorizers uses the inherent misogyny of its circumstances to expose it. There’s a reason the camera lingers on Lee, Chen, and Yao’s devastating responses to being objectified and assaulted. Ho and Sung want us to acknowledge the human cost of rape culture, both in the moment and afterwards—when the damaging, knee-jerk perception that sadly creates victim-blaming becomes more important than actual facts. They take us to uncomfortable places by showing how easily we jump to conclusions when we’re without the full picture. And they force us to confront the reality that the full picture doesn’t always mean our conclusion was wrong. Monsters can sometimes stumble into heroics while remaining monsters. Love can sometimes be blind and yet hold true. Every story possesses an agenda.

Terrorizers premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival.