We are the pale blue dot of Earth? No. We’re the intermittently blinking light on the end of an out-of-touch parent’s device for transparently spying on the electronic path of a daughter she should be proud of for being smart, compassionate, and unlike the messed up teens populating the local high school. Our world is different from what it was when Carl Sagan filled the Voyager spacecraft with records of music, different languages, and the call of whales. Now in a post-9/11 America we must fear strangers, friends, peers, and even family members from causing us the type of excruciating pain we used to reserve for the stuff of nightmare. We have begun to get scared of how small the landscape of life has become and in turn have forgotten just how inconsequential we are to the grand scheme. To your husband, wife, child, confidant: we are everything. That doesn’t mean we aren’t allowed to sometimes fall.

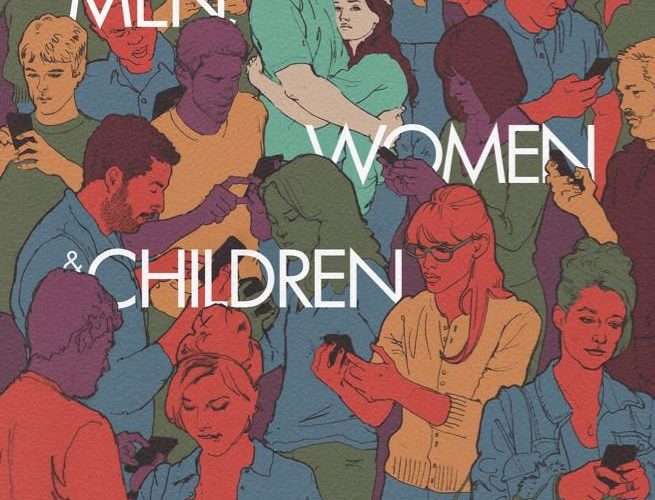

This is a good sentiment to have when walking into Jason Reitman‘s Men, Women & Children because it is a definite valley in a career I have effusively praised. It’s not as misguided as Young Adult–maybe not even as much as Labor Day, which I loved regardless–but it finds itself believing it has something profound to say when we already know it too well. Is that really his and co-screenwriter Erin Cressida Wilson’s fault or author Chad Kultgen‘s? Probably all three in equal measure for not realizing how ubiquitous their subject matter is. I’d have given Kultgen some slack if the book was written earlier than it was, but by 2011 we had already been entrenched in a cloud of paranoia and over-protectiveness driving today’s youth into needing thicker skin than ever before to simply make it out of adolescence alive. And as far as bored housewives and bored husbands go, an affair has been an easy proposition for awhile.

A greatest hits of millennial struggles, the real problem with the film is how it has been constructed. Using disembodied narration by Emma Thompson, one can’t not think about Stranger Than Fiction and let the comical nature of it taint your ability to buy into anything onscreen being authentic. A storybook feel is manufactured that makes everything seem more fabricated and cliched than it obviously is already. As it is the filmmakers must use extreme stereotypes to get their point across, but rather than use then to subvert they appear to believe these creatures actually exist in the same small town. Maybe the dark fairy tale quality is more self-aware then I’d like to believe, but I was always held at arm’s length because of it.

How could you not when Jennifer Garner‘s Patricia Beltmeyer is GPS-tracking and transcribing her daughter’s every move on the internet for daily consumption? Yes, her character is the most egregious, but the others don’t fall too far behind, despite retaining at least one foot in reality as well. I’ll admit that my parents are a little more on the pulse of new technology than most, but I still find it hard to believe Judy Greer’s Joan Clint doesn’t know she’s pimping her daughter or that Dean Norris‘ Kent Mooney thinks his son is better suited to having friends that would drop him the instant he quits football than faceless hoards of MMO trolls. Don’t get me wrong, the actors embrace these generalizations with more complexity than they may deserve. Reitman seems to wrongly think that’s enough and I then wonder what a guy like Todd Solondz could have done with the same material.

Just the title itself is pretentious in the aftermath of watching because it purports that this is what all men, women, and children are like as a rule, when in fact I’d say half of what’s onscreen is a minority experience. A better title would have been Individuality, Sex & Privacy, because they are the real issues at hand — they’re just using the contemporary family as their canvas. By focusing so much on the people doing the actions, the actions themselves come off as devices to wax on further about the fallibilities of man. Continuously going back to the narration of Sagan’s Voyager flying farther and farther into space to make us choke on how we aren’t the innocent explorers we once were is condescending. And utilizing such a sprawling cast to ensure every age type and gender within them are represented ensures none earn enough time to truly be real.

There are some exceptions. I thought Norris was great at portraying a tough guy father forced into being the caring parent he hoped his wife would always provide. Rosemarie DeWitt is stunning as the complacent wife seeking sexual adventure in a way that Adam Sandler’s insecurity shtick can’t quite match as her husband feeling the same. Elena Kampouris‘ Allison approaches getting the correct amount of time to be meaningful before being cast aside for less depressing subject matter–as if any parts weren’t depressing by their progression’s end–and Olivia Crocicchia‘s Hannah is much more complex than initial reactions may allow. The real stars shining above construction, tropes, and pretention, however, are Ansel Elgort’s Tim and Kaitlyn Dever‘s Brandy.

Tim actually embracing the film’s through-line of Sagan philosophy to really look outside himself and discover who exactly it was that he did things for is inspiring. Brandy meanwhile finds the love in what her mother was doing to her is as commendable. Her calculated rebellion never stretches too far towards transforming into something she’s not simply to hurt the jailer Mrs. Beltmeyer has become. It could be because they were the two characters I related to, but they handled the lackluster material so well that the rest seemed inconsequential. Thompson’s narration cast too comical of a hue and the subject matter of adultery, teenage miscarriage, and suicide was too dark and too much at once. It looks fantastic, does wonders visually integrating social media text boxes, and has effective performances despite inherent caricaturization, but it adds nothing to the discussion of a post-9/11 world — Men, Women & Children merely exploits it.

Men, Women & Children premiered at TIFF and opens on October 3rd. See our complete coverage below.