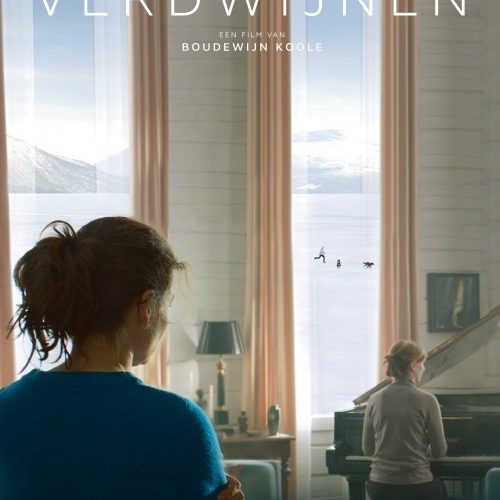

Vignettes depicting a young girl playing the piano on a darkened concert stage come and go throughout Boudewijn Koole’s Disappearance. They provide bookends to the whole, his film seemingly a visual representation of the melody—both as this single chapter in Roos’ (Rifka Lodeizen) life and its entire duration from birth to death. It’s only during the end credits that we’re finally told who this girl is: Young Louise (Eva Garet). The mystery lay in the fact that Roos played piano as a child too, giving it up at the same age (eight) her mother (Elsie de Brauw’s elder Louise) continued onto an illustrious, decades-spanning career. And while Louise beautifully breathed life into so many concertos, the composition that proved most difficult was always her daughter.

As Koole’s director’s statement reveals, he and screenwriter Jolein Laarman chose death as the inspiration of a story more attuned to life than the absence of it. That’s not to say we’re given jubilation or unwavering love throughout—life isn’t that simple or without struggle. But it also doesn’t mean those things are completely out of the question either. Sometimes it’s only when you know the end is nigh that you can allow yourself to open up to the possibility of forgiveness and understanding. Grudges as a human construct are only effective if both parties are alive to bask in their petty vindictiveness and endure it respectively. Such resentment almost has to transform into regret upon discovering one half of the equation will soon be leaving this world.

Even so, death isn’t on our minds until halfway through. Disappearance instead deals with the aforementioned struggle of life first. The players in this not-so perfect family are Louise, Roos, and her thirteen-year old half brother Bengt (Marcus Hanssen). He’s their mother’s pride and joy, an unorthodox musician keen on aural juxtapositions mixed on the computer with a project playing meticulously developed (and tuned) icicles in their backyard under way. Bengt is Roos’ joy too, though. You could say he’s the only reason she comes home every year (on his birthday) during the down time her job as an international photojournalist provides. She tries to approach her mother with kindness and promise, but the two have simply never truly gotten along for reasons yet to be elaborated.

The tension underlying every encounter between the two makes it seem this year is more difficult than others. Louise can barely feign interest, always engaged in another activity whether teaching piano or tending her giant acreage of land and multiple sled dogs. And when Roos falls on her sword to forgive her for last year’s unnamed argument, it can’t help but come across as more self-serving than apologetic. But it’s not like Louise meets her halfway, laughing at the notion that it is she who needs to be forgiven and not the other way around. As such, Roos sticks to young Bengt for fun and laughter while also calling upon an old flame (Jakob Oftebro) who’s since married with child. She hopes to cultivate better memories than before.

And it all stems from the truth of the filmmakers’ inspiration: death. It’s Roos’ mortality that has her trying harder than probably ever before to really connect with her mother. It’s why she takes an interest in what her brother is up to beyond mere surface platitudes. But the conversation she needs to have with them all isn’t one to simply dump on them if the circumstances aren’t conducive. She can’t talk to Bengt about it until Louise knows and every potential chance to do the latter is often met with the same abrasiveness that’s kept them apart for so long. As anyone knows, sometimes the only way to breakthrough these invisible barriers bolstered by familiarity is to scream rather than whisper. Playing nice supplies opportunities for escape.

Roos can’t afford another false start. If she leaves without confronting past, present, and future all at once, there might not be another chance. So things must escalate to violence. Until emotions force them to their breaking points, the ease of walking away is too great. It can’t be another case of Roos storming off and Louise saying “good riddance”. Either Roos needs to weather the inevitable chaos or Louise must ensure she cannot run away. It’s in these ebbs and flows of truth bombs and discomfort that we realize how different these two women are—and how different Roos and Bengt are too, regardless of their age gap. Underneath those disparate traits and ambitions, though, is the same blood. They may have forgotten, but love still remains.

Herein lies the beauty to what Koole and Laarman have put onscreen with this somber drama of life’s last gasp at reconciliation and understanding. Too often we find ourselves remembering the good times after it’s too late to share the memories. In these circumstances they become tainted by regret and the notion that you could have tried harder or could have called. And for much of the film it appears as though this will be just such an example if not for those words left too long unspoken arriving to challenge each other and provoke a fight rather than flight. Only together can those memories be more than bittersweet despite the knowledge that death awaits. Only when a dialogue is had can thoughts be comprehended rather than interpreted.

And the experiences had along this road are forever complicated. No relationship presented here is simple. Whether it’s the love shared between Roos and Johnny despite a future together being impossible or the rather modern European dynamic between Roos and Bengt that would make a Puritan pass out let alone blush, we aren’t watching melodrama for the sake of melodrama. Koole and Laarman have instead drawn an authentic look at broken families and their ability to simultaneously be separated by a huge chasm and closer than ever before. Both Lodeizen and de Brauw shine in roles augmented by a depth of character dialogue can never deliver as effectively as expression. We recognize them in the pregnant pauses of pursed lips wanting to say more yet remaining silent nonetheless.

Topping it off is a gorgeous locale and beautiful cinematography capturing every frozen waterfall and mysteriously welcoming mountain in the distance. The wide expanses of pristine snow soon-to-be trodden by Louise’s dogs ensure we realize how small we are compared to nature. To see Roos and her mother miles from any other living soul therefore instills the hope necessary to believe they may be able to put their egos aside and repair those years of abandonment felt by both. Without saying that knowing when your time’s up is a blessing, such knowledge can produce the incentive assumptions of infinite time yet to come never could. So while death is its driving force, I agree with Koole that it’s not Disappearance‘s subject. That’s actually our heart’s strength to mend.

Disappearance premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival.