So much of our desire to exist is based in control. We have the ability to move our homes, restart careers, and work towards a future of our choosing. No matter how difficult things become, there’s always a hope for better or an avenue towards change. It’s only when we’re cornered without an exit that we start to let our fears rule us rather than the infinite possibilities in our grasp. We search for meaning and answers, struggling to reconcile that happiness may have always been an illusion to mask the pain. And it can disappear in an instant — one hiccup along a path of tenuous certainty throwing perfect plans into chaotic turmoil. Suddenly we can no longer take the reins of our circumstances. They begin governing us.

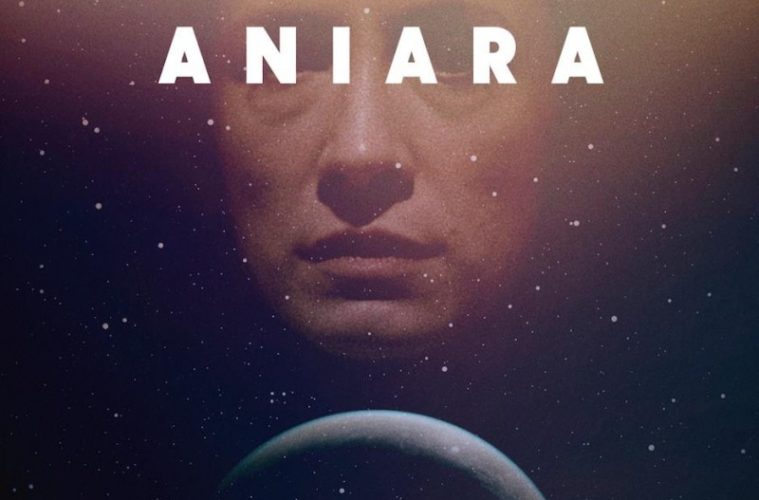

There’s no bigger example of this truth than our premonitions of apocalypse. Beyond religious scripture lies the science that we aren’t long for this universe — at least not in context with its breadth of time and space. We recognize previous extinction points and realize ours will arrive sooner or later whether from a dying star or our own steady dismantling of those intrinsic properties for which Earth seemed to have in abundance. Our art has attempted to give shape to what that desperation will look like either via our futility to prevent it or our technological advancement to cheat death and inevitably destroy another world too. One such example is Nobel laureate Harry Martinson’s 1956 epic poem Aniara, which Pella Kågerman and Hugo Lilja now bring to life.

The title shares its name with a city-size spacecraft ferrying humans from Earth to Mars in barely three weeks. It’s a routine trip that’s never run into problems with many passengers already having family on the red planet to greet them upon arrival. But there’s a first time for everything as a small field of debris forces Captain Chefone (Arvin Kananian) off course. Unfortunately a screw breaches their hull anyway, pushing their nuclear fuel supply to critical mass. Expelling it may save them for the moment, but without it they cannot steer. So despite having enough self-sustaining electricity and algae (for air and food), there’s no way to return onto their necessary trajectory. Either a celestial body interrupts their path to slingshot back or they simply drift forever.

How will everyone react? Chefone does his best to assuage fears by saying it’ll be two years tops before they can make their way back, but that’s enough of an increase from three weeks to throw people into hyperventilation regardless. Some find it impossible to cope while others realize living on Aniara with its many activities might actually be better than a dying Earth or a bleak Mars. The latter don’t have anyone or anything awaiting them and would have been continuing aboard the craft for the next ferry anyway, so why not make due and work towards calming those who can’t? MR (Emelie Jonsson) epitomizes this role as supervisor for MIMA — a spiritual, living tool used to mine consumer memories and recreate the serenity of their past.

Maybe a handful of people cared to experience what MIMA had to offer before the catastrophe. They didn’t need that sort of escape from the infinite blackness of space because they had the distractions of shopping mall boutiques, alcohol, and games. Once the reality that this vehicle was in fact a prison, however, passengers flocked to MIMA as though it was a drug to shroud their despair with manufactured euphoria. Acting as a transactional service of sorts, this machine can only handle that suffering for so long before it too acknowledges the fruitlessness of its mission. Eventually it will see how the pain it was being fed could never cease, questioning its own life in kind. And without its images those lost souls would know nothing but misery.

What follows is the devolution of mankind to its basest desires. Think High-Rise in space, the existential crises of being trapped in this cage feeding anxieties until sanity becomes hard-pressed to sustain. Chefone finds himself consumed by the power his position as captain affords — the trepidation and fear of mutiny at the start transforming into an entitled confidence as though a king lording over his court. Cults begin to rise — one built by a mother who was inconsolable at the news she wouldn’t be attending her son’s fourth birthday party (Jennie Silfverhjelm). And even those who appear too jaded to be affected (Bianca Cruzeiro’s logistics specialist Isagel and Anneli Martini’s unnamed astronomer) find themselves slowly losing their grip on life’s meaning against the vastness of space.

We therefore gravitate towards MR as the single inhabitant of this ship who hasn’t completely lost her head. But just as Martini speaks about how one can’t know why his/her relationship ended while still inside it, perhaps MR was losing her grip along with the others and we simply didn’t notice. Every chapter ticks off days, weeks, and years through an instantaneous cut to black and all we see is a new world vastly different from the old. So while appearances may not seem drastically changed, underneath smiles and laughter lies a river of dread hidden with varying success. Hope can still rear its head and breathe fresh life into those still remaining, but it often only leaves them more defeated once its promise is left unfulfilled.

Kågerman and Lilja bring Martinson’s poem to cinemas with a stark beauty both in its sci-fi production design and emotionally wrought performances. They present how life is meaningless without a destination — how we’d rather numb ourselves to the helplessness of our situation than embrace the little control we retain. It’s a fascinating character study since Earth is itself a complex self-contained ecosystem floating in space. What then makes Aniara so different? Or does the growing sense of defeatist malaise manifest precisely because it’s not? Perhaps this spacecraft is merely providing a glimpse at humanity’s unpreventable demise relative to size and population. This is centuries of mankind’s brightest dreams dissolving into dust. We’re such a miniscule part of the universe that survival will always prove just out of reach.

Aniara screened att the Toronto International Film Festival and opens on May 17.