Godfrey Reggio––New Mexico’s irascible, irrepressible, eternally eccentric monk-turned-academic-turned-filmmaker whose wordless Philip Glass-scored 1982 masterpiece Koyaanisqatsi transformed American avant-garde cinema––has finally debuted his new 50-minute film, Once Within a Time. As always without conventional plot or dialogue, Once is an eclectic, nearly indescribable feast of visual and aural ideas, at once an expansion on and radical departure from Reggio’s Qatsi trilogy, which combines the aesthetics of early-20th-century cinema with modern digital techniques for a thundering parable about the society of the smartphone and its uncertain future. Ridiculous and provocative, garish and sublime, didactic and obscure, the headtrip of a film Reggio dubs his “Kittyqatsi” is a theatrical fairytale “for children of all ages” as liable as any movie in recent memory to trigger a wildly different response in each person who sees it.

On the eve of its release, we sat with Reggio for an unfiltered, free-for-all conversation on everything from his filmmaking past to his cinematic, philosophical, and literary inspirations to his technology-driven crusade against technology to revisiting his 2002 film Naqoyqatsi, and plenty more in between. How do the tools we use affect our consciousness? What truths can music and poetry contain that facts and data cannot? Is environmental catastrophe inevitable? Has Reggio met the late Cormac McCarthy? Who are his favorite artists of the former Soviet Union? Would he describe his politics as anarchist? What does he think of his work inspiring viral spoofs made in Grand Theft Auto? Why do Jews and Catholics make good friends? Who wins between cats and dogs? Read on for the answers, and then some.

The Film Stage: Many might not know that your early work for the New Mexico Civil Liberties Union was to raise awareness of technology––phones, cameras, computers, satellite communications, etc.––being used to compromise privacy and manipulate behavior. Almost fifty years later, there’s practically no one in the world who doesn’t take this for granted. Even within my lifetime, the degree to which ordinary people now routinely volunteer information once considered private has accelerated to a point that I couldn’t have imagined as of, say, 2002. What first tipped you off to the fact that this was where things were heading?

Godfrey Reggio: Well, we tried to study the data. In studying the data 50 years ago, we found that AI was already in play, that everything was done through statistics. What Snowden talks about now, on steroids, was already in the trenches of the foundations of the federal government. And corporations––they have a conjugation that takes place. They’re a part of the government, as it were. So we saw that and we did a project on it. Not only did that occur, but the form of the films I use occurred, because all of those little spots were done with only music and image. Only one had the spoken word, and it was whispered. And those had an enormous effect, in addition to the billboards we did: no explanation, just a big eye or a social-security number. The adverts had people calling into the stations to find out when the next advert would be on. So it was a primal experience, for the point of view and for the form that I use.

[With this latest film], Steven [Soderbergh] was going to help me raise $6.5-7 million to do what’s now Once Within a Time. He got back to me and he said I can only give you $2.5 mil. I said no, forget it, go back and get some more. [But then] I thought about what we had done in the ACLU campaign, and an hour-and-a-half later said I’ll take the money. I felt less was more. So that film became a 52-minute film, which I’m very happy about, because in a way––if this doesn’t sound pretentious––films may be timeless. It’s not the hand of the clock, but the intensity of the time. You can have an intense experience in [just] a moment and it’ll stay with you for the rest of your life. So that’s how Once Within a Time got started.

The ACLU shorts are still startling, even today.

I don’t know if you’ve seen the [preliminary] stuff we did for Koyaanisqatsi, all the sets we did. They’re absolutely hilarious. But I couldn’t use them then, because it would have been too didactic. Now it’s comedic. Harvard has all of those.

[Laughs] I’ve seen some of the pictures. [Note: They are viewable in the Harvard archive, as well as on the Koyaanisqatsi Criterion Collection disc release.] Some of the images look like they might have found a second life in Once Within a Time, in a way.

[The images of] Once Within a Time, except for a few shots, were all from the other films I’ve done––most of which have never been seen! [Laughs] Or when they came out they were put down. Everything in that film we reused because if you recontextualize it, like a picture, everyone sees a different picture. So it all fit right in. That’s why I call Once Within a Time a “Kittyqatsi.”

[Laughs] You introduced the film at the MoMA premiere that way, and I was going to ask about that.

Well, here’s the thing: there’s a relationship between Koyaanisqatsi, Naqoyqatsi, and Once Within a Time. Naqoyqatsi is the contemporary version––done years ago––of what’s happening exactly now. Once Within a Time is the same story––in a different form, but all about the same subject. It’s with kids, for kids of all ages.

I noticed that there are a lot of direct connections [with Naqoyqatsi] and even some specific images reused.

A lot of the images are the same, especially at the ends of the pieces.

You’ve said that your films are not strictly anti-technology, even though they depict the negative impacts––

No, I didn’t say that. I said that technology is the most important change of the last 5,000 years, and no one knows it. Technology is the price we pay in the pursuit of our technological happiness––that pursuit is the destruction of the planet. We’d need three or four or seven other planets to [satiate our] infinite appetite on a very small plate. So I said, when in Rome, do as the Romans. We speak that language. If we were firefighters, we’d make fire to fight fire. I adopt, paradoxically, the tools that I’m questioning [in order] to question the tools. Now, some people don’t like that; they think I’m a hypocrite. They can think whatever they want. It doesn’t bother me because it’s free.

Do you get what I’m saying? I’ve used the medium. All of the films, from the beginning through the media campaign to now, were all about technology. Every one of them. Because it is the main event and it’s not seen. Those who read the New York Times and the Washington Post and watch CNN and Fox News––all the bright people––are the people that know the least because that’s all propaganda, from my point of view. The real news is never in the papers––what’s going on behind the scenes. So I try to spend my time not reading the paper but investigating what’s going on behind the scenes, which started with the ACLU. We had Barry Goldwater Jr., the son of the right-wing heavy, come in and speak for it. Because he was a Republican it was strategic, but he was the first guy who saw the danger [to] privacy being abated through technology. The Church Commission, they used all of our research to put into the Congressional record way back then. All of what we did is in the record.

What are your preferred sources of news or intellectual stimulation, then, in the current environment?

Merle Haggard! I listen to music all the time. [His work is] autobiographical. He’s a criminal, you know. He’s like Mike Tyson: famous, but can’t get famous because he went to jail for involuntary manslaughter. So I like that. I love Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring––it changed music forever for me. I listen to Philip Glass constantly, because I think he’s a one of a one, like a Mozart––there’ll never be another Mozart, and there’ll never be another Philip Glass. And he’s the most ripped-off composer on the planet today! So I listen to a lot of music. I listen to Russian music, I listen to Gregorian chants, I listen to Indian drumming with the high women voices––I listen to music all day long. It goes directly to my soul. It doesn’t go through metaphor. That’s why it can be so powerful in film: it doesn’t illustrate. It has its own road that conjugates with the image. The image is made up of the aural and the visual: one without the other is like “a dawn without a day.” And that’s what art cinema could be.

Once Within a Time is a very elaborate tribute to Georges Méliès. Are there any other filmmakers you feel loom large over your body of work?

Yes, I have a filmmaker. Look him up: Artavazd Peleyshan. He’s world-famous in the Russian world. He’s from Gyumri, the oldest city on the planet. He’s an Armenian. If fire or electricity is the metaphor: I make sparks, he makes lightning bolts. He’s a devout communist––not of the Putin ilk, but of socialism. He was never allowed to make a feature film because he was more brilliant than the rest of them. So he [mostly] did some special effects. His longest film, Our Century, is 50 minutes. But he’s a great, great, great filmmaker.

There are other filmmakers I like: I like Alfred Hitchcock a lot. I like the guy that made The Shining. What’s his name?

Kubrick?

Yes. He uses the “Dies irae” all over. So does Alfred Hitchcock. They understood the power of those five notes. I learned them as a young monk at fourteen; I could sing it to you. Philip’s first assignment with [Nadia] Boulanger after he left Julliard, in Paris, was to learn the five magic notes of the “Dies irae.” They’re everywhere! [The Liberty Mutual jingle] “Liberty, Liberty, Liberty!” They’ve been ripped off everywhere. Advertising sells more through sound than it does through visual.

I noticed, in Once Within a Time, “Dies irae” is used to introduce what looks sort of like a Japanese toy robot…

[Laughs] There you go! Well, that’s the second version of it: the first version appears as you see the ruins of modernity, and the little monkey chimpanzee. The second one is done with the same music, but with a different tempo [and] with foghorns.

Hmm. I guess I registered it most consciously during the robot-reveal scene.

Yeah, because it’s so slow. And so deep. It hits the ground floor.

I’ve always wondered, or maybe assumed, that Koyaanisqatsi in particular is a film in dialogue with Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera.

Yeah, but that’s a didactic movie, as brilliant as it is. Like Leni Riefenstahl’s movie, as brilliant as it is, is didactic. [Vertov] even writes a book about how the camera can be the gun. It was all strategy; he does everything in a strategic way. Artavazd Peleyshan is not didactic. I do everything I can to be autodidactic. So [Vertov] is a brilliant filmmaker, for sure, but he’s not one of my filmmakers. The making of Once Within a Time is a strategy, but the object is Once Within a Time.

I guess my reading had always been that Koyaanisqatsi is kind of a rebuke or a rejoinder to Vertov’s approach.

Well, [the comparison] was used a lot when it came out. Some serious critics brought that up.

So Once Within a Time, the “Kittyqatsi,” is very much its own work with its own style. But it also has this concrete relationship with the Qatsi trilogy. How, specifically, would you describe their relationship in your mind?

Well, Once is theatrical, dramatic, with actors; a plot that has no plot, but many plots at the same time, that is linear and nonlinear at the same time; that is clear and ambiguous at the same time; that leaves you with a question that only you can answer: “Which age is this: the sunset or the dawn?” So in other words, the audience completes the subject. If we were at the museum, everybody goes in and sees a different picture. That’s the modality I take.

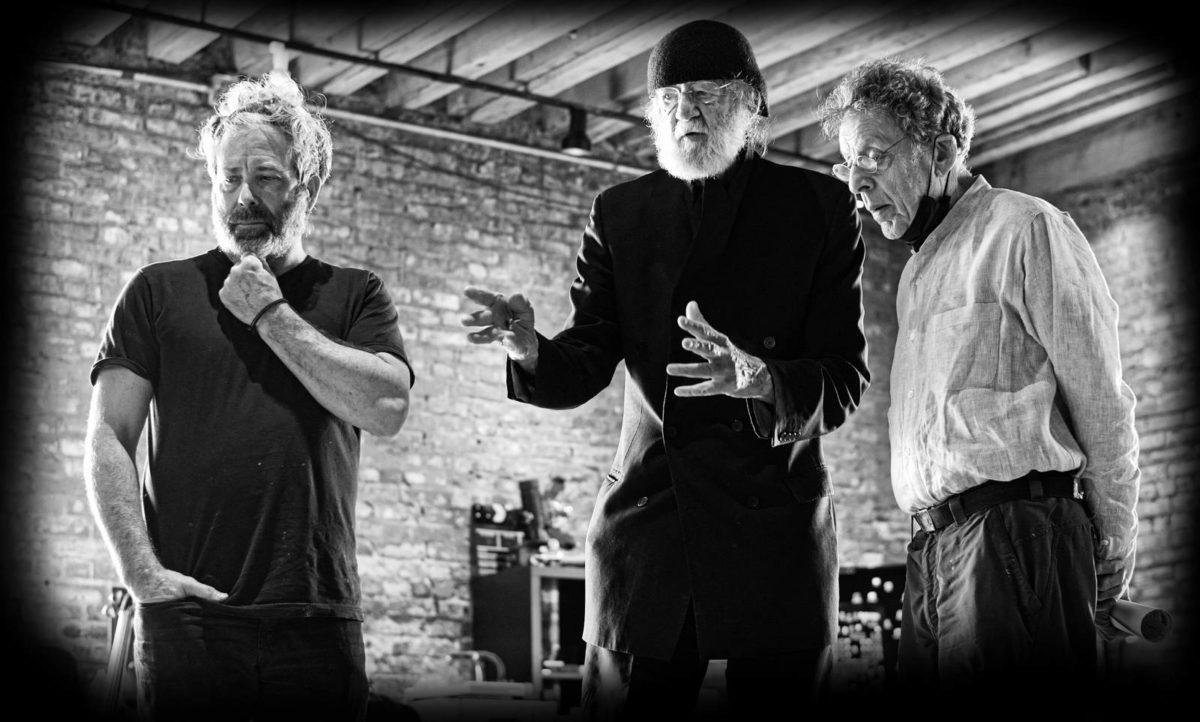

Now, that film, if we transliterate months into years: nine years is the pregnancy. I spent eight years here in Santa Fe writing this. I’ve never written a score––I’ve always written talking papers, but I wrote this out in such a deliberate way that we followed it almost to the T, for 16 months in Red Hook producing it. So it became a different experience for me, something I’ve wanted to do since I first saw Luis Buñuel’s film, Los olvidados––that’s another guy––and it led me into film. I had been working with street gangs for years and wanted to make that same kind of movie about street gangs. But I didn’t know how to do so without words. Now I’ve learned how to make a film without words. [Laughs] It’s all connected.

Did the street gang project ever get off the ground, or was it only conceptual?

Now it’s getting off the ground. It’s using ranchero music. PBS is already starting to shoot it; we started a year ago. And it’ll be in the manner that we shot [Once]. It’ll be hilarious and tragic at the same time: burning down police stations, going into fights with police, going into prisons. Big demonstrations. All of that we did years ago, here in Santa Fe. It was like our Vietnam here.

So during what period of time did you assemble the footage for this?

Well, some of that footage was being shot last year, and some of it is still to be shot. What that schedule is, is going to be up to PBS.

Okay. So, given that all of your films are about technology and about humankind’s relationship with it, do you ever feel that your work is akin to science fiction?

No! The fiction of science––just the opposite! Its truth has become the truth: if you can’t measure it, touch it, taste it, smell it, feel it, it ain’t real. Descartes says, “I think, therefore I am.” I disagree. I speak, therefore I think, therefore I am! Speaking is the first language; it’s not the handmaiden of thought. Thought occurs by speaking it. That’s our first language, our lingua franca: body language, facial expression, eye behavior, song. The stars, the alphabet, the wind. The four elements, five if you include ether; now six, with money. So it’s all connected that way. I’m a––what would I call it?––a “primitive radical conservative.”

Like, a primitivist?

A primitivist! Yes. When we first arrived here, two-to-300,000 years ago, our brain was as big then as it is now. Our best name is homo faber, not homo sapiens. Homo faber means we become the tools we use. Now our tools are taking us off-planet. Before, the first tools were the net and the spear. We’re predators, you know. Of course you know that. Humans are human animals. So Human an Animal, a beautiful book by René Dubos. I recommend everyone that and A God Within; he’s a Nobel laureate for chemistry. Was.

So are you friends with any scientists?

Oh yes, I am, yeah! For the ACLU campaign I had a whole group of scientists from Los Alamos as my committee, so I’d know what I was talking about. I give regular lectures at the Santa Fe Institute. I gave the keynote address three years ago, on the nature of time. Now, it’s only my point of view… they learn more about me than the subject, probably, when I speak. But yes: I have connections to the people that create the madness.

So this was not in my questions, but now that you’ve mentioned the Santa Fe Institute, I have to ask… did you ever meet Cormac McCarthy? He was one of my favorite writers.

No. Well, he attended some of my lectures and he wanted to come over and see the film, but he got deathly ill and he died a few months later. He was 90 or something like that. So I never got to meet him that way, only at social occasions. He was one of [my favorite writers] too.

Once Within a Time stands out for the heavy presence of children, and I imagine in some ways being intended for children. My day job involves a lot of face time with children, and seeing the film I felt children might enjoy it and I would have enjoyed it as a child.

Well, it’s a family movie. Kids are not of the future: they are the future, now. It’s they who are in play. They make up more than half the demographics now. So today, you know, a kid will have seen and heard more in one day than a kid in the Middle Ages in their whole life. So they know what’s going on. [Once] is made with children, but for the children in all of us: you, me, old people––we all have a child within. It never disappears. Baudelaire says, “Genius is childhood recovered.” That’s why Greta Thunberg plays a part in the film: she’s like the Joan of Arc. Everybody knows her. It’s why Mike Tyson is there; he’s a felon. It’s precisely because he’s a felon that I wanted him. He knows on the street he’s famous, but the agency doesn’t want to touch him because he’s a rapist. [He’s the] smartest guy I’ve ever met.

What is the presence of children in your personal and professional life?

Well, again: I’ve worked with street gangs forever. I have families of kids that still come see me, some of them as old as the fifth generation now. Over a hundred. Kids are in all my movies. I made a movie, Anima Mundi, for children, and it was one of the most successful videos of that day, and that got me really thinking about kids––because I didn’t intend it for kids, but it came out as something that kids ate up. It’s 72 animals… someone once said, “We’ve not seen ourselves until we’ve been seen through the eyes of another animal.” When I was a monk I took a vow to teach the poor gratuitously, to live with the poor. Took a vow to do that because that’s what the order of monks I was in was about. Their monastery was in the city, not outside. Kids are in all my movies. As you and I are talking, they’re being bought and sold by Apple, Google, and everybody else.

The ways in which children experience video and media are wildly different today than they were even at the time Naqoyqatsi came out.

Wildly different. If we count it in old-language time, then it doesn’t seem far away; if we count it in technological time, we’re a thousand years from there. If not more. Time depends on spacetime. The world has homogenized: there’s no more sunset, no more sunrise; it’s all together, all at once, on the web. Everywhere, all together at once. And we’ve become blind. There are two things you can’t look at: the sun and death. Now we can look at both and we’re sunblind.

As I said earlier: its truth has become our truth. Scratch our surface, and there’s an “-ism” within us all. Technology is the “-ism.” We don’t even know it. Heraclitus, the pre-Socratic philosopher who spoke in aphoristic, contradictory, paradoxical terms, said: “That which is most present is least seen.” And he said: “You can’t walk in the same river twice.” Because everything’s in flux, and the road is up and down, and all, and all, and all. They’re like Hopis: they speak through orality. They were at the period at the end of the Iron Age and into the Copper Age, like us now; the whole world was falling apart. That’s why Homer could say, “Fire: our brilliance, our flaw.” Fire is technology. We’re in Homeric times: this is not a fairytale which has a happy ending. It’s a Homeric tale that has a resolute beginning.

Do you feel that there are any clear positive qualities to technology, or things that could be harnessed usefully in isolation?

I believe in burning [it] and having a big dance around the fire. Now, I’m not ridiculous. The problems we have were created by the technology we have, so we’re probably going to need technology to fix it, or we can’t be here. But that’s a slippery slope. Because all people want to do is get back to “normal”, which is itself insane… so I’d rather be outsane. You know, with a blast from the sun we could lose everything. All our gizmos, period. And the sun is in its most active period right now in millions of years, and our valences are breaking down. The blue sky above, a mere 67 miles, is now breaking apart in parts of South America and New Mexico. Big holes. That’s why we have the “skyquake” in the film.

We’re going to experience things in your lifetime––we already have in mine, and yours––that the eye has never seen before because our tools are so big. I mean, the United States has been at war for 90% of its history. The history of history is the history of war; the twins of civilization, religion, and war. The difference now, for homo faber, is that we have instruments that can instantly annihilate the planet, or all life upon it. And we’ve already started, [it’s] already been felt––we’ve been testing [the bomb] in the atmosphere and under the ground! When you do things under the ground, the center core responds to a different motion than the outer core, so we’re confusing the rotational patterns.

Nature is alive! What does Plato say? “Nature is indeed possessed of soul and intelligence.” Soul: anima is the word. It means the breath in, hold the breath: anything that breathes has a life. Our planet has life, but we’re killing it. Literally. Now that’s not being an alarmist; that’s real. We could appear completely healthy and have sudden collapse in a moment. That happens to people; it can happen to the earth. Sudden collapse.

[This sounds] heavy, I know, [but] I’m a dark person that’s hopeful. Unless you can be hopeless about putting Humpty-Dumpty back together again––which I am, I think it would be ridiculous––then you can be hopeful, bold, to recreate your own world. That’s the greatest opportunity we have. The greatest prayer is the prayer of creativity. We’re here to be like the unknown Creator; creation is all about creativity. Production. We all come from the same Big Bang. So the great prayer for me, as a monk, is creativity. That’s how I can be most like the unknown God, and everybody else.

So you think, then––as I understand it––that the future which avoids apocalypse is the one that synthesizes a new way of living which has not been tried.

Right. Right. Let me see how I would put it… at the end of Koyaanisqatsi, [the title card] says, “a way of living that calls for another way of life”. So [given that] we’re in Homeric times, truly, the same world coming apart as then when the Greeks put the logo into everything and made it clear, which was the worst thing… the Jews, of course, in the Old Testament [in Hebrew], there were no magic vowels. It was all by commentary: everybody had a different point of view. It was autodidactic. The Greeks came in and made it not subjective, but [introduced] objectivity through the word. The logo.

So it’s a slippery slope we’re in. Wittgenstein says, “The limit of my language is the limit of my world.” We see the world through language. When our language no longer describes the world, then it’s time for what’s called a “reboost,” and the etymology of “reboost” is not by word but by object. By deed, by action do we survive. In other words, we’re not [in] Lord of the Flies waiting to get back to normality, which happens at the end of that powerful film. We’re running away from normality. That’s what’s insane. If that sounds extreme, we’re in extreme times.

Are there any trends in the modern world that give you hope for the future?

Young people! They can see through [and] pierce the veil of commercialization, the Los Angelization of the planet. They see it. We all have to be part of it, myself included––we don’t have a choice. It’s the environment, technology. When I say “technology,” I’m not talking about this gizmo or that––I’m talking about [everything]. It makes 1984 look like a sideshow. It’s the whole organization of life. It’s as ubiquitous as the air we breathe. Being sensate, we become the environment that we touch, smell, taste. It’s not by accident that they’re called “iPhone.” It could be “iTechnology.” We are technology. We’re living the fiction of science as we speak, me included. All my films are autobiographical, I only wanna please myself. That’s the only person I have a chance at maybe knowing.

You’ve said before, as recently as the MoMA Q&A and as far back as some of the promotional materials for Naqoyqatsi, that we’re all already cyborgs.

Absolutely. Everything I’m telling you I’ve said 10,000 times, but I’m trying to give it to you in [such] a manner that I hear it for the first time through my speech to you. There’s no inconsistency. If you go on the web, go to Facebook or YouTube, I have a thousand lectures and masterclasses all over that. I didn’t even know it ‘cause I don’t use it––until I came back here and had to use it. And I’m saying the same thing every time, all over the world.

So you feel that your outlook on the world has pretty much not changed in the last 50 years? Or has it evolved in some ways?

It’s not changed; it’s only gotten more intense. You know Dylan, the poet: it’s “blowing in the wind.” The future is in the present. There’s only one other tense, and it’s in the Bible; I can’t remember which book. But the future-present reads this: that the tragedy must be, but it need not be! In other words, that you can enter into history and change. So I do all my films, grammatically, [in] a syntax for the eye. The time is the future-present. The location is the genius loci: every location has a memory that never goes away. The subject is unspeakable, eating the earth. The verb may be hopeful––children!––and the clarion call is the object, the call to action. [A] Chinese proverb says: “In times of social crisis, the single most important thing to do is to rename the world you live in.” It’s like calling out your demons. They don’t like that; it’s an exorcism.

[Chuckles] I’m getting way out there.

That’s okay––I like it! One of the things that I find most compelling and unique about your entire body of work, cinematically, is the way in which you strive to poetically illustrate philosophical theories and concepts without using language. Among the thinkers you’ve most frequently cited as informing your work is Guy Debord.

Yeah, well he’s just one of them. Jacques Ellul, Ivan Illich, Leopold Kohr more so. I like Guy Debord as well. He was really a fluxist. [That’s] from Heraclitus. If you look [at France] 1968’s unbelievable connection between the workers and the students, it was the fluxists from Eastern Europe that organized with Guy Debord. I met him once but he’s a mysterious guy; he was in the room but he wouldn’t see me. But I saw him. I didn’t like his movie either, Society of the Spectacle. I hated it. But I loved his writing.

[Laughs] So you liked the book, Society of the Spectacle?

Yeah. I didn’t like his movie at all.

Correct me if I’m wrong, but I believe the image you’ve said you wanted to use as the title of Koyaanisqatsi originally [was from Society of the Spectacle].

Oh, yeah. Yeah. Nobody bought that. But now you’ll see with all the corporations, the tennis-shoe company has a big check, everybody uses a symbol now because that’s the language. I wanna say that Koyaanisqatsi’s language got picked up everywhere, from Madonna to traffic to news. It’s all over the place! Coppola used it first, when he left Zoetrope, with the clouds. It’s a language. It’s not an exclamation point!

Some of the visual concepts in Naqoyqatsi specifically reminded me of Baudrillard’s Simulacra and Simulation.

Right, and I’m a big fan of his. His book has this great “highway into nowhere.” You’ll see the highway all over Once Within a Time, especially in “Act III: Time Will Tell,” when you’re seeing the ruins of modernity; everything’s got that big highway leading right to the hourglass.

In addition to those you’ve credited in your films, who are some contemporary philosophers or thinkers who––

Joseph Brodsky! Look him up. He was in the gulag; he was a poet. He got the Nobel Prize for poetry. He’s a Russian who had to escape from Petersburg and the gulag. W.H. Auden hosted him in Austria, then he moved here. He knew more about English than we did: he had to learn it [as a second language]. Whenever I read his books––not his poetry, but his essays [like] “A Room and a Half” [or] “Less Than One”––they bring me to my knees. I need a dictionary to read them. He knows English better than anybody I’ve ever read. So I like him a lot.

I like Octavio Paz a lot: “All meaning in the form. What you thought you put into it, there’s much more there that communicates.” I’m a big fan of his and––as I mentioned––Plato and Heraclitus, the pre-Socratic philosophers.

Ivan Illich, I call him a brother. As a monk I did all my retreats once a year in Cuernavaca [and] got permission from my superiors to go with him. I didn’t wanna join his group of “de-professionalized professionals” because I don’t like to join groups, but he and I had a close, close personal relationship. I’m so lucky to have had his interest and friendship throughout his life––I saw him a month before he died in Florence. Jacques Ellul I was also a good friend, the most-plagiarized writer on technology in the 21st [and] 20th century both.

A lot of these thinkers you’ve cited are often thought of as being aligned with anarchism.

Yes, they are––the most misunderstood subject in the world! Anarchism is against the homogenization of life, how boring it would be: one weather, one bird, one language, all the stuff with the Tower of Babel, which is a precursor to the world we live in now. We all speak the language of technology. So yes: these people were anarchists. They were not bomb-throwers, they were idea-throwers––which explode bigger than any bomb may explode. And I follow them because I believe in the veracity of that. We live in an homogenized world now. There’s no sunset, there’s no dawn. There’s data, not language; there’s memory, not the genius loci; I could go on and on and on. We live in two different worlds. But anarchism has––by design, by the Americans and the Russians––[a reputation of] crazy bomb-throwers, lunatics, [and] madmen. It’s quite the opposite: they’re the poets and the writers!

I recently discovered that Tolstoy considered himself an anarchist.

Yes, he did. And there’s no question that Dostoevsky considered himself an anarchist. None!

So would you say their brand of pacifist anarchism is closest to your own outlook?

Well, in a way. But, you know, those words have big fruit hanging on ‘em already. So I’d rather be able to define my own path, as I’ve done with you.

[Laughs] I like that! I like not accepting labels.

They limit you, and that’s usually done by people [who] have a preconceived notion of what you’re doing. That’s happened with all my films––[they call me] “prophet of doom” and all this shit. They’re very hopeful films! They’re comedic as well! So I made one that’s really comedic, at the end.

Tragedy’s twin is [comedy]! Aristotle wrote about it, but that book disappeared. Umberto Eco wrote a book called The Name of the Rose, [about how a] book is deep somewhere in the Vatican archives about humor. Humor questions authority: that’s who we are. Baudelaire says, “The smile of the Mona Lisa is the stigmata of original sin.” Put that one in your pipe!

[Laughs] I was going to mention: speaking from my own experience discussing your work with other film enthusiasts, I think some people may have an idea in their heads of Godfrey Reggio as this very serious guy. At the MoMA premiere Q&A [for Once], though, you had the audience laughing out loud about every other minute!

‘Cause I’m a child! I never grew up! I flunked kindergarten! So I’m lucky! I don’t think Soderbergh ever grew up, or [Once co-director] Jon Kane either. I’m just a little more expressive. And the whole film is based in play. Play, play! Literally––play! That’s what kids do, they think through the imagination. This film is aimed at your reptilian brain, at the right hemisphere, the hemisphere of dream which controls the subconscious––”as above, so below”––and to question your left brain. Done deliberately, so that there is a lot of nonsense being [spoken]. There’s no words in the film.

Would you say you’ve made a conscious attempt to be funnier over time, or has the world only gotten more absurd?

I would say: I think Koyaanisqatsi was a comedy! But I’m in a rare position there. Naqoyqatsi especially, with all the adverts and the madness and Icarus, at the end, spinning out…

“Writers are the engineers of the soul.” You know who said that? Joseph Stalin! Writers are the engineers––not the architects, the engineers––of the soul. The madman himself, his whole interest in life was to live in movies, to create scripts.

I will say, I laughed at the Madam Tussaud’s wax museum scene in Naqoyqatsi.

Oh yeah, that was great! And Donald Trump was in there, before he was [news]!

Yeah! I watched it earlier this week and I was not prepared for that!

[Laughs]

That’s a good piece of evidence for the claim that your films foresee the future!

Well, in Naqoyqatsi we also saw the World Trade Center with a big flash behind it.

Yeah. It feels very much, watching it today, like simultaneously a film of precisely 2002 and also of the 21st century in general.

Well, we were in the ring’s eye of 9/11. War-life, “life is war” beyond the battlefield. Civilized violence. That was [not only the meaning of “naqoyqatsi”], that was happening as we were making Naqoyqatsi.

Right! And watching it… I was a child back then, but it brought me vividly back to the emotional state and general awareness of the currents that were going through American society at that time. I think it captures the experience of living in that moment quite well.

Oh, good. Good.

I also noticed that in both Naqoyqatsi and Koyaanisqatsi, you use video games as––at least by my reading––metaphors for the programmatic nature of postindustrial society. Naqoyqatsi contains a montage of footage from shooting and combat games

Well, [Naqoyqatsi] also happened to coincide with the first big mass shootings in Colorado. And the [Los Angeles] riots, with the police going nuts and the [Korean] community coming out shooting guns, and that shit.

Have you ever played any games yourself?

No. I don’t have a computer. I’d get addicted! My “computer” is 72 boxes on a wall that I can see. I don’t want to use a computer. [I mean], everything comes to me by way of computer, but other people help me… I just don’t wanna get involved. I can’t, now, though I have to know all the nomenclature and all of that. But everything comes through Laura [Sok, my assistant] or our distributor, Oscilloscope.

I ask because I feel like in some ways the semiotic vocabulary of games can be somewhat similar to your own work. They can convey ideas to the person experiencing them without using language––

Hey, let me stop you: Grand Theft Auto used Koyaanisqatsi’s images and music!! [People remember it] til this fuckin’ day!

[Laughing] Yeah To advertise, right?

Yes! The images are all over! There’s a guy in Dublin [video artist Alan Butler] who did a comparison and he shows it in museums all across Europe! [Note: actually a full-length recreation he made himself, separate from the original advertisement.]

Did he consult you about that?

Oh, yeah. I met with him before, when I could travel.

I think, in particular, the digital and game images in Naqoyqatsi were striking to me in terms of speaking to how people in a society of digital overload process or experience reality through simulation. And that looms large in the minds of children who are growing up in this world.

Oh, boy. They’re addicted. Way beyond the gizmo, as I said; it’s the very breath of life.

Are you interested in any digital art?

Well, I’m going to have a conversation with AI. I’m taking Dostoevsky’s The Grand Inquisitor as my point of view. And we’re gonna interrogate each other; someone’s setting that up for me. AI’s also been using my stuff and stealing things and making me look like a man from 3,000 years ago, and all kind of weirdness…

[Laughs] I meant more likeL artists crafting images using digital mediums.

Well, we used some of that in [Once]. We made our own programs. I was with young kids from all over the world––average age 27––they could rip off anything that was born into their mind at birth, and they could create anything with it. So we used all of that, fire to fight fire. But most of it was not [CGI], just a few little things. Like the wolves howling at the moon, with the [smartphone] gizmo in the moon. It was all done digitally, but made to look like film. Every frame is hand-painted digitally to make it look like it was made in [the early 20th century].

Right. It looks like sort of an anachronistic Méliès film.

Indeed.

On the topic of digital vs. AI: some of the themes in your work recall, of all people, James Cameron…

A digital monster.

[Laughs] …but on the other hand, we’re clearly on the verge of Hollywood films that are literally directed by an AI with no human at the controls.

Well, like [George] RR Martin, who wrote all these beautiful books… AI has taken over all his stuff. He’s trying to sue them! They just changed the names; they took the whole plot, the characters, changed the names and rearranged things a bit and they completely ripped him off. That’s part of the [strikes]: AI taking over the business!

They can bring Marlon Brando back to the screen, they can do anything… “If it can be done, it will be done,” says Andy Grove, the founder of Intel. If it can be done, it will be done. That’s true in war, it’s true in cinema, it’s true everywhere. There’s no limit. [We have] infinite appetite. And everything is on speed at rush hour, outrunning our future, getting quicker and quicker and quicker. So that’s why we could have a sudden collapse. We don’t know what we’re playing with. When you listen to all the discussions on AI, they all say how wonderful it is, but “we need control.” And then they all have to say “Well, you know, AI is perhaps smarter than us!”

If it can be done, it will be done. It’s already running the world. It’s called “A-regular-I.” “ARI.” That’s what they call it.

Once Within a Time closes, unexpectedly, on a Homer Simpson quote.

[Luaghs] Yeah!

I was wondering, based on that and on your films––especially Naqoyqatsi, using images of popular culture––are there any pop culture works that you find especially valuable or illuminating?

I’m sure there are, but the truth is I don’t look at many films or anything like that. It takes me so much energy to do these films. I don’t want to sound ridiculous, but it does; it takes all my energy to focus on it. So I don’t watch a lot of other films. I have people around me [who] see things. I like some filmmakers a lot. I like Coppola’s use of sound a lot in Apocalypse Now. The instrument of war that changed [the Vietnam] war was the helicopter, which is the first thing you hear. We made a monster machine that could shoot people, rescue people, bomb people, napalm people, in all kinds of versions of the helicopter. So I like that. Who did the Kennedy assassination movie, [and the Vietnam one] and all of that, what’s his name?

Oliver Stone?

Yeah, I like his films because they’re all real. They’re based in his own experience. So I like that.

And, I assume, The Simpsons.

Oh, I know George Meyer! Principal writer for 25 years, he’s retired now. I wanted him to work with me on [Once] because I admire him so much––he’s the funniest guy I know and very shy. A Catholic like me! I asked him and he said, “You know, Godfrey, you’re asking to do the Holy Grail of humor. I wouldn’t have a clue, but I wish you well.” And that actually helped get me even more determined to do it, because the master told me he didn’t know what to do.

So I tried to do the Holy Grail of humor, the silent film by gesture and by body language––where [they’re] the storyteller, not the story. There’s only seven or eight stories, anyway, forever. They’re all involved with love and deceit and war and jealousy and lust and all those things. It’s the storyteller; it’s how you tell the story.

This question is a little more personal, but it’s something I was curious about: I saw an older interview where you made a reference to mental-health difficulties impacting your outlook and your work process…

Oh, yes, I have mental illnesses. I have obsessive-compulsive states; I still do. I have automaticities, which I have learned to control. I used to stutter badly, which I have learned to control. I have psychosomatic illnesses and I have mania. That’s where the word “maniac” comes from, but I have a rare form called scriptomania; I have to write everything down. I write it on my body, on paper, on the walls, on everything. I have three-and-a-half––next month it’ll be four––tons of writing at Houghton Library at Harvard, most of which has been digitized now.

So yes: I have a lot of “problems,” let’s say. As a young brother I used to wash my hands ’til they bled, so they wouldn’t send germs around the room. I couldn’t lick a letter to my family; I’d send them all my microbes and germs. It’s a horrible thing, but it’s done me real good.

I found it very topical since, as I’m sure you’re aware, one of the notable issues of the first world––especially in the last 20 years or so––is this massive, multi-generational mental-health crisis.

I’m right in there with ‘em! We’re not mentally ill––we’re out-sane. The world is mentally ill, and the world gives us all unspeakable trauma.

So do you feel that there’s a relationship between mental illness and creativity?

Absolutely. Look at Nietzsche; he ended up in a loony farm. Look at Artaud: the same thing. Yes, there’s a relationship! Consciousness originated in the split of the bicameral mind. Read Julian Jaynes’s book, [The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind]. We used to hear the words spoken, like schizophrenics hear words; they’re real! That’s who we are! But all that got divided into right and left brain. They used to conjugate. We would hear the truth. All mystics would rather hear the truth than know it. Thomas à Kempis, the mystic writer of the late middle ages, said in The Imitation of Christ: “Would you rather know love or feel it?” Well, of course you’d rather feel it. And mystics are usually loonies! [Laughs]

I think Once Within a Time sort of gets at this: that the cyborg consciousness of younger generations seems to be contributing to this particular generational crisis. That it’s sort of tearing their minds from their bodies.

Right. It’s terrible. New Mexico has the highest suicide rate of kids––I’ve known some of them myself––of any place in North America. I don’t blame them for that. It’s just part of their journey. They can’t handle it anymore. It’s too phony; it’s too full of stress. The image is more important than reality. There’s a lot of pain out there. Pain becomes the only truth for a lot of people, and it’s depression and you’re gone.

Right. I feel like––based in part on firsthand experience––one of the isolating factors for people in that wheelhouse can be that participation in society is predicated on this kind of performance that they feel like they just can’t keep up.

The adverts don’t leave you alone. They’re picking at you like animals all day long.

Yeah. So for my last question, turning to a much lighter subject…

What kind of food do I like––is that what you’re gonna ask? [Laughs]

No. [Laughs] It’s in that general wheelhouse, but I think a little more thematically on-topic.

[Laughs] Okay, go for it.

Do you have any pets?

Oh, yes! I’m a big fan of felines! Dogs live, normally, seven years or so––there are exceptions, because they have wealthy patrons who can give ‘em every operation on the planet––but cats have nine lives. Dogs treat you like gods; cats treat you like equals. I have a cat, now 18 years with me, a feral cat who’s probably 165 years old. Nobody knows the age of cats. Many people say when they’re born, they’re born 30 years old. My cats love me! Cats have no facial muscles, but they close their eyes for love. Their tongues come out. There may be a little “meow.” So I live with cats all over the place. Feral cats, cats at home. And raccoons and skunks, they’re the sweetest. They all get together, you know, it’s only we that say they don’t get along.

I’ve heard my cats having arguments with foxes in the neighborhood where we live.

[Laughs] Cats can be heavy, boy. They’ve got these big claws that they can stretch out. A dog’s no match for a cat.

Heavy physically, or heavy emotionally?

Well, they’ll hurt you physically with their claws! The dog has fixed claws; he’s got the big teeth, but [the claws will] never get there. With cats, the claws can come out and they’re like needles! If a dog gets hit on the nose, they’ll go running away!

I noticed this! I live with a cat and a dog, about the same size and the same color…

They get on great, as kids! And they will as adults, too, but we make them enemies… none of them are enemies. I saw a film the other day, 24-hour footage in the bush, and there’s a baby elephant with two baby lions, just [truckin’] all around.

They’re very emotionally complex animals, cats.

Yes, and they suffer! Think of what Perdue Chicken does to the turkey and the chicken… oh my god. They suffer! They have real feelings! They’re animals like we are! We fuckin’ suffer! Like having their nails pulled out!

Yeah.

It’s monstrous. The industrialization of the animal, all of them. The fish, the beef, the pig.

Are you a vegetarian?

No, because I’m a predator. I do eat, but I don’t have teeth anymore, so I just munch rice and oatmeal. But yeah, I think it’s okay. Like, when the animals first got together––this is not just me, this is real––there was huge respect between those that ate and those that were eaten. That was the rule of the day. I know that sounds strange, but that’s what it was. It wasn’t Perdue Chicken.

I’ve seen similar ideas expressed in works about Buddhism. Of the understanding and acceptance of an inevitable, cyclical nature of consumption.

Many Buddhists cut the body up and leave the bones out for the birds to take. That’s how they do it. Hindus burn the bodies; Christians bury the bodies; etc. Now you can take a little cocktail and kill yourself, you can do whatever you want.

[Laughs] I would share more chicken bones with my animals if they weren’t a choking hazard.

[Laughs]

Anyway, thank you so much for your time!

Thank you. Tell me your first name again?

Eli.

Eli what?

Friedberg!

Friedberg. So you’re Irish?

No, Jewish. [Beat] [Bursts out laughing]

[Laughs]

[Laughs] I’ve gotten weird questions before.

I’m a crypto-Jew myself.

[Laughs harder] Many of my favorite artists are! Jews and Catholics, I think.

I work mainly with Jews. I never tried to do that; it just so happened.

[Laughs] You know, I noticed this was true of Cormac McCarthy as well. A Catholic who got on very well with Jews.

Yes. Well, we’re very close.

A lot of artists and intellectuals in those two groups. I think it’s the angst. Anyway! Koyaanisqatsi is one of my favorite movies of all-time. I rewatched it last night; I think it’s still beautiful, sublime. So it was a privilege to be able to have this conversation.

Thank you. So let me just say this in ending: the [making-of featurette] for Once Within a Time is a pedagogy of how to make a movie with fun. Even though it’s about Once Within a Time, it applies to every movie I’ve made. The methodology is the same. So please check that out.

Once Within a Time is now playing at NYC’s IFC Center and opens on October 20 at LA’s Braindead Studios. See more playdates here.