With an awards season and year-end lists that tend to favor films that have been released in the last few months, there’s many films that can go overlooked. For our yearly feature highlighting the 50 best films you might have missed––arriving before our overall top 50 films––we’ve sought to dig deep to find the gems that deserved more attention upon their initial release and have mostly been left out of year-end conversations. Hopefully, with many widely available on a variety of streaming platforms, they will begin to find an expanded audience.

While many documentaries would qualify for this list, we stuck strictly to narrative efforts; one can instead read our rundown of the top docs here. We also haven’t included 2024 films that only got awards-qualifying runs this year, including Universal Language and Armand. And while there’s some films that deserved bigger audiences, such as Here, Juror #2, Horizon: An American Saga – Chapter 1, Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga, Drive-Away Dolls, and Sing Sing, we’ve focused on the smaller-scale gems that, for the most part, didn’t have the benefit of a full-scale theatrical roll-out.

Check out the list below of U.S. releases, as presented in alphabetical order.

Allen Sunshine (Harley Chamandy)

Directed with a sense of tranquil serenity and grounded maturity one might be accustomed to finding in the work of a seasoned director, Allen Sunshine is, quite remarkably, the debut feature of 25-year-old Harley Chamandy. The Montreal-born, New York-based filmmaker received the 2024 Werner Herzog Film Prize for his feature following its Munich Film Festival premiere earlier this year. Having participated in Herzog’s workshop as a 17-year-old, Chamandy’s shared affinity with the legendary German director for the natural world is quite apparent. Shot on 16mm by Kenny Suleimanagich, who brings a painterly touch in capturing the woodland landscape, Allen Sunshine is an affecting, understated look at picking up a life destroyed, and finding a connection with the people that can help put the pieces back together. – Jordan R. (full review)

Art College 1994 (Jian Liu)

The disquieting and foreboding feelings of Liu Jian’s Art College 1994 is refreshing in contrast with the college-set films that can’t wait to cake the experience with nostalgia. It’s a very matter-of-fact film that presents college life through the semi-embarrassing philosophizing and the arrogant naivete of not having any answers, but never shutting your mouth anyway. For many, it’s the way it actually was, but we’d rather not remember it as such. That may take the conventional idea of ‘fun’ out of a college film, but I can’t say that this honest and somber portrayal, in its muted color scheme and decidedly non-expressive animation, is not enjoyable in and of itself. It takes the snapshot of youth on the precipice of a breakthrough. While obnoxious and optimistic, it lends its characters and their lives the dream of possibility despite not providing any answers to their feeling of being lost. – Soham G.

Blackbird Blackbird Blackberry (Elene Naveriani)

Georgian cinema continues to show thriving signs of life in Blackbird Blackbird Blackberry, a film about a contently independent woman who is faced with the thrills and spills of companionship for the first time. A breakout at Directors’ Fortnight at Cannes earlier this year and a deserved winner, last week, of both best film and actress at the Sarajevo Film Festival, Blackbird is the latest from Elene Naveriani, a 38-year-old director who co-wrote the script with the writer and feminist activist Tamta Melashvili. From that collaboration springs an unlikely tale about the shock of attraction, about how bodies appear depending on how we see them and who’s looking, and about the joys of touch and solitude and whether or not they need be mutually exclusive. – Rory O. (full review)

Chicken for Linda! (Sébastien Laudenbach, Chiara Malta)

A charming animation with bite that went overlooked upon its premiere at the Cannes sidebar ACID last year, Sébastien Laudenbach and Chiara Malta’s French feature Chicken for Linda! is a vibrant, moving, and playful mother-daughter story, following a widowed mother’s mission to make a chicken with peppers dish (which her late husband perfected) at the request of her daughter. Hand-drawn with bursts of expressionistic fancy, the film is a testament of the power of animation, the only medium that can convey the true colors of a spectrum of emotions and movement. – Jordan R.

Chime (Kiyoshi Kurosawa)

Relegated to a mystifying worldwide NFT release, Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s first of three films this year (the other two still without U.S. distribution) is very much worth tracking down. As Rory O’Connor said in his review, “How do you even start to write about Chime, a film that keeps secrets guarded and lives off the shocks of its knife-edge turns? It’s safe to say the director is Kiyoshi Kurosawa. It’s also safe to say Chime is 45 minutes long, making it feel more like the pilot for a TV series we’ll never see––only adding to the intrigue. Like much of the director’s work, it’s the kind of thing you could have seen late night on television when you were much too young. It would have also left a mark.”

Chronicles of a Wandering Saint (Tomás Gómez Bustillo)

Tomás Gómez Bustillo’s charming, intelligent Chronicles of a Wandering Saint is a natural follow-up to the two short films for which he is known: Soy Buenos Aires (a strange, picaresque rags-to-riches tale) and Museum of Fleeting Wonders (a collection of dramatized paranormal happenings). In Chronicles, as in the two short films, he is primarily concerned with spiritual, ethical, and religious contrasts; scenarios in which miracles are mixed with coincidences, faith with rationality, and boredom with inspiration. But that is where the comparisons end; for Chronicles is in every way a more serious, controlled, and moving work of art, which stands with the very best of contemporary Argentine cinema. – Oliver W. (full review)

Close Your Eyes (Víctor Erice)

Curious, self-referential, and rich, Close Your Eyes has had a difficult passageway into the world, with its Cannes world premiere dogged by reports of conflicts over its runtime, its non-competition placement, and Erice’s own in-person boycott of the screening. Its final form also is a scarcely believable one, singular and self-possessed even amidst all the latter-day auteur work that’s screened in recent days: although it’s studded with other media, such as an unfinished film of Garay’s and trashy Spanish primetime TV, the main bulk is a pokily shot mystery “procedural,” told mainly in one-to-one dialogue scenes, shot in judicious singles with minimal coverage and muted lighting. But Erice is gradually able to accrete a rich character study of Garay and, yes, another meditation on the Grand Power of Cinema––not that we’re lacking in those at the moment––enriched by the fact that this theme, together with memory and longing, has long been the director’s modus operandi. – David K. (full review)

Club Zero (Jessica Hausner)

Across her five previous features, Austrian director Jessica Hausner (Amour Fou, Lourdes, Little Joe) has developed a distinctly unique tone––one which carries through her sixth outing Club Zero. Led by Mia Wasikowska, the dark satire follows a nutrition teacher at an elite school whose relationship with five students takes a dangerous turn. While Hausner is perhaps intentionally poking the bear as it relates to eating disorders, one could swap out the subject of her new film to another topic du jour and still retain a cogent, one-of-a-kind look at cult mentality. – Jordan R.

Coma (Bertrand Bonello)

A contemporary cliché that weakly attempts to diagnose what ails us in modern life is the idea of being addled by technology––of our minds and attention spans swamped by screens, content, scrolling. But as the pandemic hit this notion gained a new relevance: it’s not that the virtual realm of content and media was luring us away from our reality––faced with an indefinite lockdown, it had finally become our sole one. Even though this can be poorly rendered by some, it’s the more sensitive and aware artists, such as Bertrand Bonello with his new feature Coma, that remind of the urgency to confront it. – David K. (full review)

Daaaaaalí! (Quentin Dupieux)

At the time of year where every other film is a biopic chasing prestige respectability, we are lucky to have Quentin Dupieux, the prolific, serious-minded, silly filmmaker perfectly positioned to take a sledgehammer to the genre. His second 2023 feature has been described as a “real fake biopic” of Salvador Dalí but is best understood as a return to the heightened analysis of cinematic storytelling à la 2010 breakthrough Rubber––a movie which increasingly looks like the rare weak spot in a filmography equal-parts playful and thoughtful. – Alistair R. (full review)

Disco Boy (Giacomo Abbruzzese)

To Disco Boy’s credit, while its core themes and imagery are second-hand, it does attempt to build, expand on, perhaps modernize Beau Travail, not unlike Helena Wittmann’s recent Human Flowers of Flesh, which premiered last year at Locarno (and actually featured Lavant playing an incarnation of his Galoup character). It’s also perhaps the first leading role of his glittering career to date where Franz Rogowski is miscast, feeling inappropriate or perhaps too worldly for the naive military grunt at the center; either way, the film’s debuting director Giacomo Abbruzzese attempts drawing out a performance that hits predictable notes of machismo, despair, and anguish. – David K. (full review)

Dream Team (Lev Kalman and Whitney Horn)

Following their singular take on the Western genre with Two Plains and a Fancy, filmmakers Lev Kalman & Whitney Horn returned to the festival circuit earlier this year with Dream Team, an absurdist homage to ’90s basic-cable TV thrillers. Starring Esther Garrel and Alex Zhang Hungtai, with a producing team that includes I Saw the TV Glow director Jane Schoenbrun, Leonardo Goi said in his Rotterdam review, “Like its predecessors, Dream Team hangs in a hazy, oneiric region; what the film is about is a lot easier to discuss than the entrancing feeling it evokes. As corals the world over start killing humans with poisonous neon-colored gases, INTERPOL agents No St. Aubergine (Esther Garrel) and Chase National (Alex Zhang Hungtai) are dispatched not to figure out so much as to ‘learn about’ the mystery, per their own admission, in a journey that keeps shuttling us from Mexico to British Columbia. Split into seven episodes, each given a beautifully evocative title (e.g. ‘Asses to Ashes’ or ‘Doppelgängbang’) and introduced by slightly different, growingly trippy renditions of the credit sequence, Dream Team apes a serialized TV structure only to frustrate the gratifications one would normally associate with the format. There’s no sense of closure here, much less clarity. As No and Chase travel south of the border, their quest gets more evanescent, and the plot––such as it is––more ethereal: storylines are dropped, new characters bob up everywhere, all while the mystery turns hopelessly intricate.”

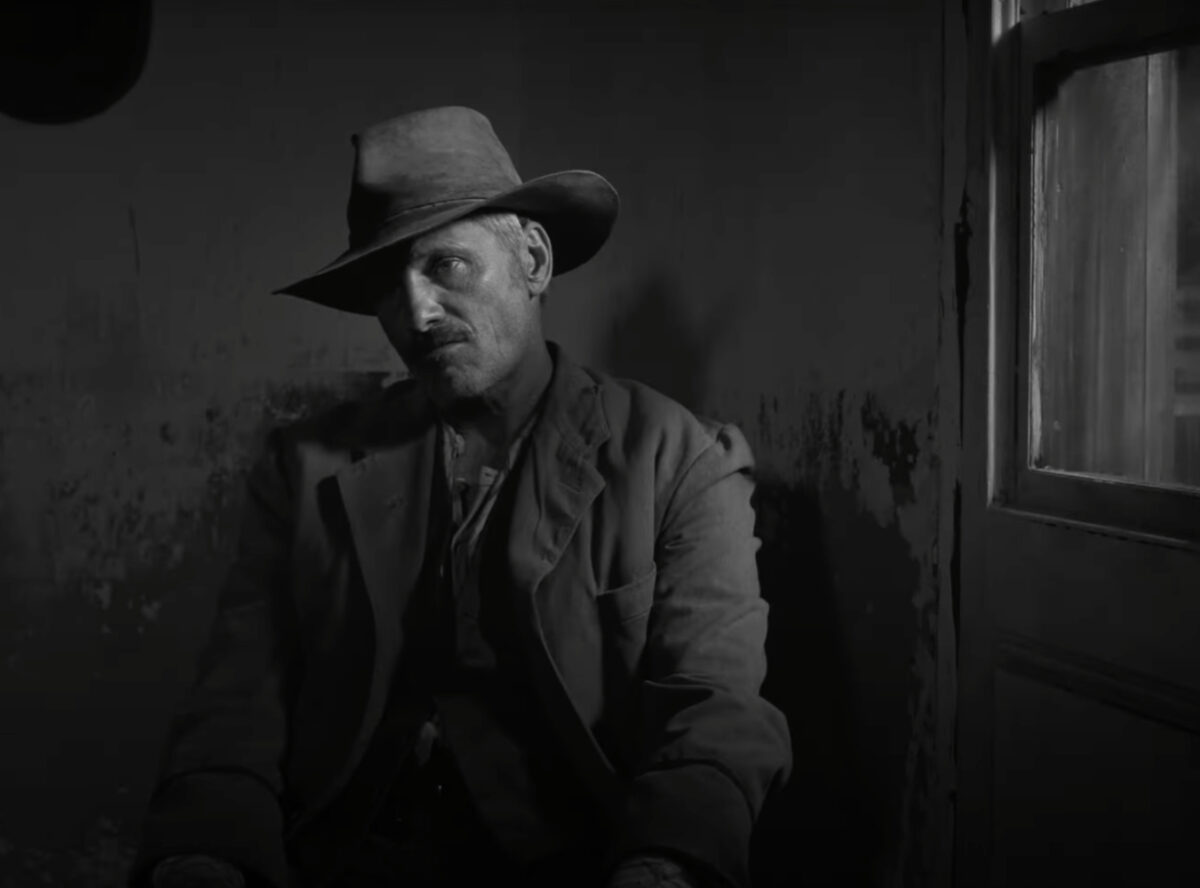

Eureka (Lisandro Alonso)

Nine years since that underground epiphany, along comes Eureka, a film that, for large chunks, seems to emerge from the same hallucinatory terrain Jauja opened up. Like all its predecessors, this unfurls as a literal journey dotted with solitary wanderers either searching for or mourning lost relatives. (“All families disappear eventually,” Gunnar was told down the cave, a line that might as well double as the director’s motto.) Old tropes and motifs notwithstanding, Alonso’s latest is his most ambitious: a tripartite film, Eureka sides not with the white strangers in strange lands that had long peopled Alonso’s oeuvre, but with the native communities facing these invaders. Its scope is ecumenical, its geography massive. In barest terms, Eureka’s designed to sponge something of, and locate parallels between, the experience of Indigenous communities stranded in three markedly different milieus: the Old West; South Dakota’s Pine Ridge Reservation in the present day; and finally the jungles of early-70s Brazil. – Leonardo G. (full review)

Family Portrait (Lucy Kerr)

One of our favorites from last year’s Locarno Film Festival, where it picked up the Boccalino d’Oro for Best Director, Lucy Kerr’s directorial debut Family Portrait finds Deragh Campbell searching for the family matriarch in an elusive portrait that has drawn comparisons to the films of Antonioni. Savina Petkova said in her review, “Family Portrait deals with inexplicable loss, but one that is contained, repressed, inarticulate. If Katy has not literally lost her mother, the absence is strong enough to become the film’s driving force. But what keeps creeping up in conversation is the actual loss of a relative to an unknown virus. Without exposing too much of the COVID reality that gripped the whole world not so long ago, Kerr alludes to the fact that we still haven’t learned how to talk about such traumatic passings. What’s omitted is also left offscreen, sharing is a whisper, mutuality is hard to reach. If the photographic medium fascinates us by giving reality its own image––one that’s separate from reality––cinema re-animates its stasis and shows us life in flux.”

The Feeling That the Time for Doing Something Has Passed (Joanna Arnow)

In The Feeling That the Time for Doing Something Has Passed, Ann, a lugubrious New Yorker, sleepwalks through her daily life––colorless job, perennially disappointed parents––while maintaining a long-term sub/dom relationship with an older man. She visits her Jewish family, goes to yoga, and attempts some Internet dating. Invariably she winds up in her boyfriend’s lifeless brownstone. Executive produced by Sean Baker, this is the feature debut of writer-director Joanna Arnow, a Brooklyn-based actor and filmmaker who made a name for herself as a wry observer of millennial sex lives and stasis with a couple of award-winning shorts: Bad at Dancing (2015) and Laying Out (2019). In Dancing, Arnow sat naked on the floor, casually asking for advice from a friend having sex right in front of her. The sense that everyone around you is getting their shit together (and maybe getting laid) is present again here; yet eight years hence, it arrives with the added humility of lived experience. – Rory O. (full review)

Free Time (Ryan Martin Brown)

Free Time opens on an office meeting between Drew (Colin Burgess) and his boss. Drew is dissatisfied with his data-analysis position because it’s too much data entry and too little analysis. “The computers do all of the analysis for you now. It’s really just… data,” he laments. The meeting ends unexpectedly with Drew surprising himself (and his boss) by putting in his two weeks notice. It’s a savvy cold open that clues us into Drew’s lack of self-awareness being a source of amusement in the narrative to follow. – Caleb H. (full review)

Girls Will Be Girls (Shuchi Talati)

In a voicemail to a crush two years her senior, Mira (Preeti Panigrahi) wonders if her feelings are “puppy love [or] maybe it’s big dog love.” Directed by Shuchi Talati, Girls Will Be Girls has an unfortunate title that makes it sound like a sugary teen comedy. It’s a far more nuanced, interesting portrait of a 16-year-old girl coming to terms with a sexual awakening and her young mother, who never quite had the chance to experience one either. – John F. (full review)

Good One (India Donaldson)

It’s been nearly two decades since Kelly Reichardt’s Old Joy showed how the wilderness can be an open canvas to explore the breaking points of male friendship and reckoning with a midlife crisis. While those emotional quandaries are evergreen, it’s appropriate timing to bring an entirely new element to this conceit. India Donaldson’s carefully observed, refreshingly patient, beautifully rendered debut feature Good One shifts the perspective, concerning a 17-year-old girl who embarks on a camping trip in the Catskills with her father and his best friend. Through an accumulation of minute details and uneasy glances, the drama becomes a portrait of increasingly crossed boundaries leading to an ultimate breaking point. – Jordan R. (full review)

Here (Bas Devos)

For anyone keeping tabs on Bas Devos’ career, it’s notable that the drama of his latest film Here is set in motion by something as benign as a pot of soup. A charming portrait with a flânuerial spirit, the film follows a Brussels-based Romanian construction worker who, having decided to move home, cooks what’s left in his fridge, packages it up, then gifts it to family, friends and––much later––a Belgian-Chinese woman doing a PhD in moss. She is played by Liyo Gang and he is played by Stefan Gota. It’s 81 minutes long, has relatively little dialogue, and tugs the heartstrings in all the best ways. It might be the most benevolent film of this year. – Rory O. (full review)

The Human Surge 3 (Eduardo Williams)

The Human Surge 3, Williams’ second feature and follow-up to his 2016 The Human Surge (the first installment of a trilogy with no second chapter), is another stupefying project designed to push the medium toward new, uncharted paths. Like the first Surge, this too unfurls in its barest terms as a hangout movie, cartwheeling across three different countries (Sri Lanka, Peru, and Taiwan) to dog a few low-income twenty-somethings as they fritter away time with friends in-between odd jobs. But where the saga’s first episode played like three shorts stitched together, traveling across distinct settings in standalone segments, The Human Surge 3 trades that for something far more elliptical and confounding. The youngsters at its center––Meera and Sharika, Livia and Abel, and Ri Ri and “BK”––aren’t confined to their respective countries but keep showing up in each other’s locales, and the film itself seems to exist in a multiverse that collapses time and space; one minute we’re roaming the rain-soaked slums of Iquitos, the next we’re strolling past Sri Lanka’s igloo-shaped, anti-tsunami houses. – Leo G. (full review)

Humanist Vampire Seeking Consenting Suicidal Person (Ariane Louis-Seize)

It’s such a wonderfully simple yet utterly unique premise. Ever since Sasha (Sara Montpetit) was a young vampire, she’s been unable to bare her fangs. Maybe it’s the product of PTSD (after a hilarious “clown incident”). Or maybe it’s a result of her body chemistry triggering her compassion center at the sight of human duress rather than hunger like the rest of her species. Thus sustenance comes only from the blood bags others provide her. – Jared M. (full review)

Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell (Phạm Thiên Ân)

Early into Pham Thien An’s sprawling, stupefying Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell, there’s a shot that manifests Caravaggio inside a shack in rural Vietnam. Having traveled from Saigon to his home village to attend the funeral of his sister-in-law, Thien (Le Phong Vu) is visiting a local elder who sowed a shroud for the departed. The twenty-something wants to pay for the service; the old man doesn’t take money from neighbors. He does accept the company, though, and very generously spills a whole cascade of memories from the Vietnam War, laying bare an old bullet scar on his ribcage. And as Thien bends to graze the bruised skin under the warm, caliginous light, Pham frames the moment as one of reverential awe, an image modeled off of Caravaggio’s “The Incredulity of Saint Thomas.” It’s a beautiful shot in a film full of them. That it comes near the end of a particularly intricate 24-minute take is a testament to Pham’s mastery of craft; that this three-hour odyssey is only his first feature only adds to the wonder. – Leonardo G. (full review)

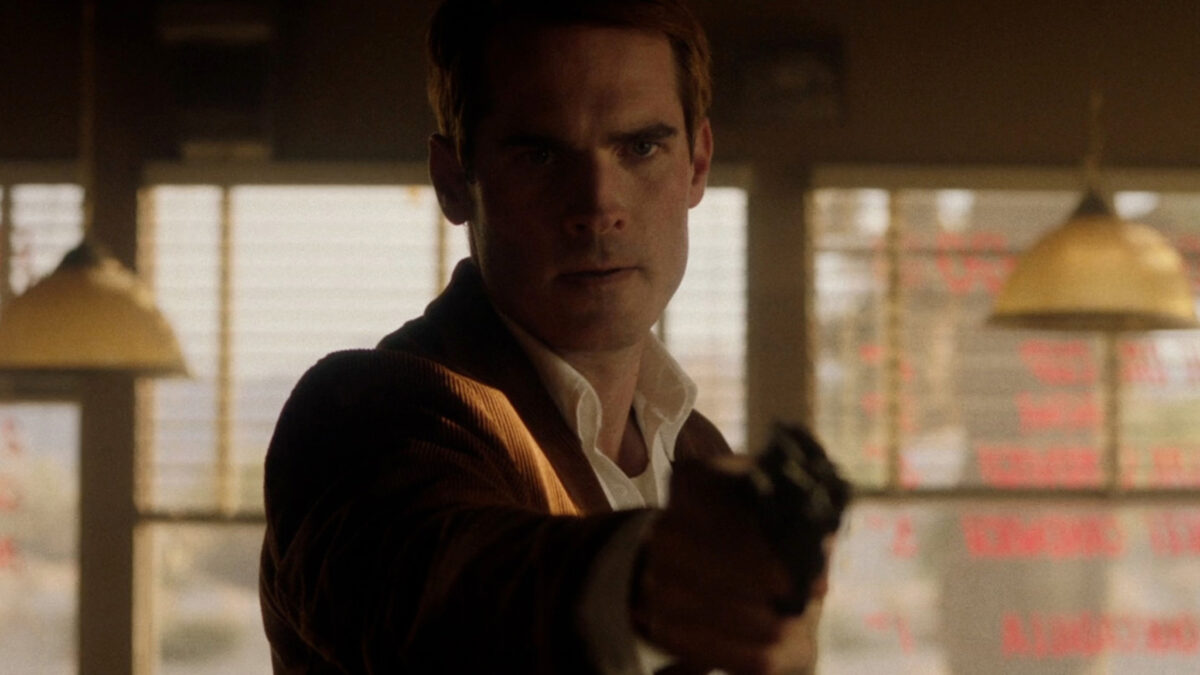

The Last Stop in Yuma County (Francis Galluppi)

After watching Francis Galluppi’s deliciously entertaining, bloody one-location noir thriller The Last Stop in Yuma County, it’s easy to see how Sam Raimi warmed to his pitch for a new Evil Dead movie and hired him for the next installment. Galluppi’s highly accomplished debut feature follows a traveling knife salesman (a pitch-perfect Jim Cummings) who gets stuck at an Arizona diner in the middle of nowhere when some nefarious criminals stop in. With dialogue and turns that would make even the Coens smile, this is an homage that has an identity all its own. – Jordan R.

Lousy Carter (Bob Byington)

What a year it’s been for David Krumholtz. In 2023, the actor has added a Tony-winning play (Tom Stoppard’s Leopoldstadt) and a box-office sensation (you know which one) to his resumé. In both cases that affable face, so often in the margins, nudged toward center stage. Krumholtz goes one further with deadbeat comedy Lousy Carter, a premiere in competition at the Locarno Film Festival wherein the actor plays a graduate lecturer who learns he has six months to live and decides to try seducing a student. It’s less creepy than it sounds and, at its best, it’s all his. – Rory O. (full review)

Mambar Pierrette (Rosine Mbakam)

Cameroonian filmmaker Rosine Mbakam uses familiar spaces as microcosms of society. After capturing her subjects in one setting, such as a mall in Chez Jolie Coiffure (2018) and the protagonist’s home in Delphine’s Prayers (2021), her narrative-feature debut Mambar Pierrette foregrounds the eponymous tailor (portrayed elegantly by Mbakam’s cousin, Pierrette Aboheu) and love for her complex family while attempting to make ends meet in Douala. She asserts a determined work ethic in her sewing, attracting a breadth of customers just large enough for Pierrette and co. to get by. – Edward F. (full review)

Matt and Mara (Kazik Radwanski)

The films of Canadian director Kazik Radwanski are freedom in its purest form, or the purest this particular medium can contain. Being the opposite of prescriptive, they sculpt themselves according to interpersonal dynamics that can otherwise be invisible, and by doing so, give shape to parallel emotional worlds, extensions of a protagonist’s psyche. That goes for Derek (Derek Bogart), the impulsive lead in Tower (2012), sleep-deprived gamer dad Erwin (Erwin van Cotthem) from How Heavy This Hammer (2015), and for the chaotic Anne (Deragh Campbell) whose quarter-life crisis makes a delightful whirlpool out of Anne at 13,000 ft (2019). The second collaboration between Radwanski, Campbell, and Matt Johnson following Anne premieres at the Encounters section of this year’s Berlinale and it is humbly named Matt and Mara. – Savina P. (full review)

Memoir of a Snail (Adam Elliot)

Grace Pudel (the voice of Succession’s Sarah Snook) is wishing goodbye to her elderly friend Pinky (Jacki Weaver), who’s currently prone on her deathbed. Once she finally perishes, Grace––who’s somewhere in her 20s, yet wears a black beanie customized with the pop-out eyelids of a snail––parks herself on a nearby bench and begins narrating her life story (in a manner that’s a tad Forrest Gump-ian) to her own pet snail Sylvie, who slowly slithers away as she’s setting herself free. Such events being in early Aardman-style claymation certainly enhances their kookiness. But regarding this animated medium, Memoir of a Snail’s director Adam Elliot (following-up his enduringly popular 2009 feature Mary and Max) prefers the term “clayography”––his own portmanteau of claymation and biography––which does someway capture the uniqueness of what he’s doing. – David K. (full review)

Molli and Max in the Future (Michael Lukk Litwak)

A feat of small-scale, inventive sci-fi with a large imagination, Molli and Max in the Future subverts the oft-repeated idea that any peek deep into the future is one with a little less humanity. Taking the mold of a rather charming rom-com, the film follows the reunions of a man and woman over 12 years and various planets and dimensions. While some of its more eccentric touches don’t fully register, Zosia Mamet and Aristotle Athari find a grounded heart to their characters and evolving relationship that ensure the journey is one worth taking. – Jordan R.

Mountains (Monica Sorelle)

A low-key, poetic exploration of life’s ironies, Monica Sorelle’s feature debut Mountains frames the disappearance of Miami’s Little Haiti with a warm, compassionate gaze recalling the masters of social realism––akin to Roberto Rossellini with the touch of Ousmane Sembène’s lighter films. With a title drawn from a Haitian proverb “behind mountains there are mountains,” the film retains a light touch, somewhat more sad than mad as Little Haiti disappears in the city’s building boom. A modest dream home is unobtainable once the real estate vultures circle the neighborhood and Xavier Sr. (Atibon Nazaire), a demolition worker, plays a role in changing his neighborhood permanently, making way for young Whole Foods-shopping professionals to displace families and small businesses. – John F. (full review)

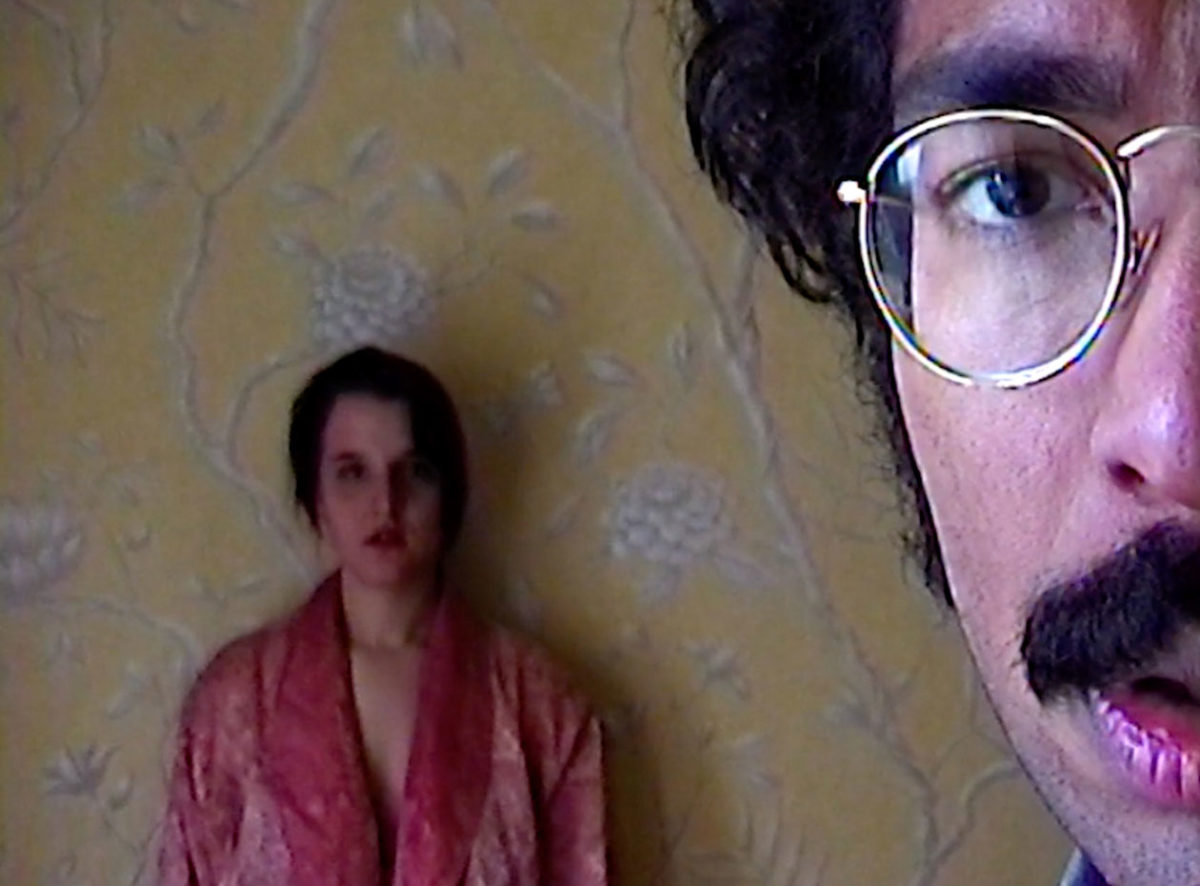

My First Film (Zia Anger)

Zia Anger’s name has been a kind of totem for underground film artistry, to whatever extent that seems to exist anymore. Her presentation-based My First Film made waves in recent years as the ultimate vision / confession of artistic failure and regret, making somewhat peculiar the existence of, let’s see what it’s called, My First Film, a feature debut-of-sorts that tells of her younger self’s failure to launch a filmmaking career. Or someone like her: the lead character is Vita, a shortsighted and temperamental young director failing to control cast, crew, ideas, or impulses; but present in the film is Zia, who reflects on this difficult time in the character’s (her?) life. Fear not any risk of complication: My First Film makes legible––dare I say universal?––thwarted dreams and personal embarrassment vis-a-vis the interplay of Anger’s actual work and Vita’s imagined endeavors. – Nick N.

National Anthem (Luke Gilford)

At the beginning of National Anthem, writer-director Luke Gilford’s exquisite-looking and subversive debut feature, 21-year-old Dylan (Charlie Plummer) lives a particularly burdensome and monotonous life. Within his small, rural, isolated New Mexico community he supports his family by shoveling gravel at temporary construction gigs and returns to his one-bedroom home to feed and take care of Cassidy (Joey DeLeon), his younger brother. Most nights his alcoholic hairdresser mother goes out late and returns home with drunken flings, forcing her two sons to sleep on the couch. It’s a difficult, lonely existence, and throughout his primary caretaking Dylan sees no opportunity to escape. – Jake K. (full review)

New Strains (Prashanth Kamalakanthan and Artemis Shaw)

While most films about the pandemic have either tried to find a genre bent to reflect our universal anxieties or provide a more anodyne look at everyday struggles in navigating our new way of life, Prashanth Kamalakanthan and Artemis Shaw’s New Strains is a refreshingly lo-fi, emotionally naked, dryly humorous look at forced confinement. From releasing sexual tension to crafting the least-appetizing meals possible to journeys venturing out in our strange new world, there is both a familiarity and a freshness in its droll view of quarantine life. Winner of a Special Jury Award at International Film Festival Rotterdam and shot on Hi8 video, the film has a threadbare aesthetic that only adds to its relatability factor, stripping down mandatory monotony to bare essentials. – Jordan R.

Only the River Flows (Wei Shujun)

Wei Shujun’s detective noir Only the River Flows (based on a story of the same name by Chinese author Yu Hua) is set in a small town along a river in China’s Jiangdong province where it seems the sun never shines. The atmosphere is unrelentingly melancholy: the town’s infrastructure is crumbling, the police have turned the local cinema into their headquarters (no one sees films there anymore), Beethoven’s “Moonlight Sonata” plays frequently, and––yes––there is a murder. – Gabrielle M. (full review)

Pamfir (Dmytro Sukholytkyy-Sobchuk)

A riveting father-son story set in the criminal world of smuggling on the edge of the Ukrainian border, Dmytro Sukholytkyy-Sobchuk’s debut Pamfir has a remarkable sense of location. Astonishing tracking shots center on our foreboding lead Leonid (Oleksandr Yatsentyuk) as he picks up the pieces of his life to make ends meet for his family. There’s a lived-in sensibility to its world, giving space for raw, unfiltered emotions to play out in regard to regrettable decisions our characters make in a bid both for survival and a familial connection. – Jordan R.

The Paragon (Michael Duignan)

For a film about saving the universe from cosmic evil, stakes couldn’t be lower in The Paragon. What begins as a man’s quest for revenge takes a hard left into the occult and psychedelic, but its scope never expands outside of a small-town setting and smaller-minded protagonist. If anything, the film can’t get any bigger if it wanted to; writer-director-editor-cinematographer Michael Duignan shot it in less than two weeks on a budget of $25,000 New Zealand dollars (that’s around $15K in US currency). In other words: the film couldn’t afford corners let alone cut them. But The Paragon gives its all, embracing its DIY nature to deliver a light and breezy sci-fi comedy, and what it lacks in budget it more than compensates for in low-key charm. – C.J. P. (full review)

La Práctica (Martín Rejtman)

The near-decade since Two Shots Fired hasn’t found Martín Rejtman losing a step. La Práctica continues his reign as Argentina’s purveyor of mirthful chuckles, a patient and absurdity-spotted lens now trained on the lives of recently divorced yoga practitioners navigating dating, business, and the indignities of getting old. Not the most thrilling synopsis, I know, but it’s a concept of which Rejtman takes every advantage: running gags, sharp images lit with a kind of soft opulence, and above all a great study in what happens when you put three different types of guy in the same room. American distribution’s never been so easy for Rejtman to snag, and thus there’s good chance you’ve not yet slipped into his world. But I can ensure La Práctica is a proper first look at an unsung master. – Nick N. (full review)

Red Rooms (Pascal Plante)

Arriving more than a year after its Karlovy Vary premiere, Canadian thriller Red Rooms feels most like a dark companion piece to Saint Omer in its perspective-shifting analysis of a courtroom observer, although that’s where the similarities end. Director Pascal Plante’s tale of true-crime obsession pushed to one of its most uncomfortable logical extremes doesn’t attempt to rip up the rulebook of how courtroom dramas operate so much as it tries grappling with the sensationalized allure of murder cases, and the disastrous consequences of third-party observers feeding off the personal trauma of others. That it manages to be so critical whilst succeeding as a nihilistic thriller at face value––albeit one closer in tone to Olivier Assayas’ Demonlover than David Fincher, to whom it has been regularly compared––is its greatest achievement, a stealth satire of which Paul Verhoeven would be proud. – Alistair R. (full review)

Riddle of Fire (Weston Razooli)

Films with child protagonists present a unique tonal challenge. If overly saccharine whimsy can alienate an adult audience, having precocious kids delivering mannered performances can seem too stylized and divorced from reality––what, say, Wes Anderson has a skill for, many others do not possess. With his debut feature Riddle of Fire, director Weston Razooli tries locating the balance between extremes to uneven results. On paper, this is a kids’ fantasy, action-adventure film, yet it’s difficult to discern the precise audience to whom it may appeal. – Ankit J. (full review)

Rumours (Guy Maddin, Evan Johnson, and Galen Johnson)

While Guy Maddin and Evan & Galen Johnson’s latest endeavor brings the most star power they’ve had in a film thus far (Cate Blanchett and Alicia Vikander among them), Rumours loses none of the trio’s singular sense of humor. Following political leaders who become stranded as the apocalypse may be underway, it’s a wacky yet grounded look at the crumbling veneer of power and influence when there’s no one left to lead. Luke Hicks said in his review, “If you do know the longtime Canadian experimentalist’s filmography, then you know nothing seems less likely than Rumours, his grand, Cannes competition-grade entrance into (supposedly) normcore feature filmmaking which, when discussing Maddin, encompasses everything inside and most things outside Schrader’s Tarkovsky Ring. Even less likely is the idea that Maddin would take on modern, real-world events, the film opening on the press podium of the G7 summit, albeit one led by slightly fictionalized, more blatantly vapid versions of the leaders they represent.”

Seagrass (Meredith Hama-Brown)

Everything you need to know about Judith (Ally Maki) and Steve’s (Luke Roberts) marriage arrives during their first “share” at the summer retreat where they’ve brought their daughters (Nyha Huang Breitkreuz’s Stephanie and Remy Marthaller’s Emmy) to play while repairing whatever has broken between them. After Steve passes the buck by saying she wanted them to come, Judith attempts to honestly organize her thoughts around her mother’s recent passing. Before she can finish, however, he forcefully interjects: “Five months ago. – Jared M. (full review)

The Settlers (Felipe Gálvez)

The barbaric, bloody sins of the past come to define what entities govern certain land today, carried out by conquistadors and colonizers who hide behind righteous religious falsities to denigrate an indigenous population. With his directorial debut, a hauntingly conceived Chilean western The Settlers (Los Colonos), Felipe Gálvez localizes an origin story of this horror vis-a-vis the brutal genocide of the now-extinct Selk’nam people, who were native to the Patagonian region of southern Argentina and Chile. While spare early passages are narratively opaque and formally ornate to a distancing fault, the riveting second half––including a chilling reckoning with others occupying the desolate land and a well-executed structural gamble––brings profound expansion to this chilling story of atrocity. – Jordan R. (full review)

The Shadowless Tower (Zhang Lu)

Watching over Beijing’s Xicheng district is an enormous white pagoda, a relic of the Kublai Khan rule, so majestic and otherworldly in looks and stature it might as well have been dropped on Earth from a far-flung planet. Legend has it the monument casts no shadow––not in its immediate vicinity, at least––though its silhouette is said to stretch as far as Tibet. No other corner of the megalopolis features as prominently as this one in Zhang Lu’s The Shadowless Tower, a film to which the 13th-century wonder lends its title as well as a metaphor for the kind of permanence its drifters fumble after. And no one among them is as drawn to it as Gu Wentong (Xin Baiqing). – Leonardo G. (full review)

Small Things Like These (Tim Mielants)

Anyone looking to debate the limits of progress should cast an eye on 1980s Ireland. As a generation born in revolution and civil war moved from farms to towns, a middle class emerged. Some people had televisions; if they were good, some of their kids had Levi’s jeans. As certain things loosened, the Catholic church’s grip on most aspects of Irish life seemed to only grow tighter. Between 1922 and 1996, and aided by a callow state, the church was responsible for imprisoning tens of thousands of women (mostly young single mothers who couldn’t afford the child) into what was essentially indentured servitude. In these “laundries,” women worked seven days a week and weren’t allowed to leave. Their babies were taken from them and sold for adoption, or worse. Around 1,600 women died. The number of babies is estimated to be in the thousands. – Rory O. (full review)

Snack Shack (Adam Rehmeier)

Evolving the zippy, punk aesthetic in his previous feature Dinner in America (which also got renewed attention his year), director Adam Rehmeier’s Snack Shack is an entertaining Dazed and Confused-esque summer comedy, bolstered by the spirited performances of its leads, Conor Sherry and The Fabelmans‘ Gabriel LaBelle. Following the always-scheming best friends’ journey as they attempt to strike rich when they take over the snack shack of the local pool, the narrative ends up hitting some expected beats, but there’s a comfort in its familiar nature––conveying a throwback nostalgia that doesn’t overshadow its characters. – Jordan R.

Sometimes I Think About Dying (Rachel Lambert)

While she says her banal, nondescript, spreadsheet-crafting office job is the only thing she loves in life––besides cottage cheese––one wouldn’t guess it from the way Fran Larsen (Daisy Ridley) carries out her dreary 9-to-5 routine. Spending the labored minutes staring at leakage in the ceiling tiles, gazing at her computer screen, and barely speaking a word to her overenthusiastic colleagues, Larsen has something more existential eating away at her soul: she’s preoccupied with dying. Whether it’s being washed up on a beach, hanging from a crane outside her window, being consumed by the forest, or a violent car crash, she has recurring visions of what could be an escape from her lonely life of isolation. Although not feeling fully formed with its emotionally rushed finale, Rachel Lambert’s Sometimes I Think About Dying is a humorously droll, narratively restrained look at the feigned personalities of workplace office culture and the social anxieties of being forced into such spaces. – Jordan R. (full review)

Sujo (Astrid Rondero and Fernanda Valadez)

A film about growing up in your father’s shadow that mostly (and unexpectedly) examines the role of women as community pillars and violence interrupters, Sujo is the compelling new Sundance award-winning feature from Identifying Features team Astrid Rondero and Fernanda Valadez. The father in question Josue (Juan Jesús Varela Hernández) is a sicario, a brutal gang enforcer killed early in the film by his cartel. The first chapter unfolds as young Sujo (Kevin Uriel Aguilar Luna) watches his father conduct business at a distance, purposefully disorienting passages wherein we overhear conversations. Compounding the confusion, when his father doesn’t return home, we witness a chilling scene in which he’s hidden by his aunt Nemesia (Yadira Perez Esteban) when a member of the cartel comes to exact revenge after Sujo’s father killed his son. – John F. (full review)

Summer Solstice (Noah Schamus)

Summer Solstice took me by surprise when I first saw it at BFI Flare LGBTIQ+ Film Festival back in March. Fresh and funny, simple, but never slight, this meditative indie summer film explores the coming-into-oneself of Leo, a trans man navigating post-transition and the early stages of an acting career, and his relationship with old friend Eleanor, who knew him pre-transition and hasn’t seen him in some time. The film speaks with a voice that feels wise beyond its years, whilst openly admitting that it doesn’t have all the answers and doesn’t always know what direction to take. That voice belongs to Brookyln-based trans-nonbinary artist Noah Schamus, a first-time feature filmmaker with a background in docufiction hybrid shorts. That filmography is evident in the warm metatext that Schamus weaves through this arrestingly sensitive tale of finding where you fit and where you perhaps no longer fit. – Blake S. (full interview)

Terrestrial Verses (Ali Asgari and Alireza Khatami)

Iranian filmmaking’s reliance on formal restrictions and secrecy are given new variations in Terrestrial Verses, co-directed by Ali Asgari and Alireza Khatami, who’ve both enjoyed previous festival success with their solo features. Chiming indirectly with the “Woman, Life, Freedom” protests last year––the largest civil unrest in Iran for a generation––Asgari and Khatami take a panoramic view of its urban citizenry through nine vignettes, observing confrontations with state brass behaving at their most paranoid and arbitrary. – David K. (full review)

This Closeness (Kit Zauhar)

It’s true that This Closeness, by rising writer-director-star Kit Zauhar, may be too small in scale for some. But a recent trip to New York where this writer stayed alone in a West Village studio apartment oddly went about helping understand the particulars of the film a little bit better, even if it may be technically set in Philadelphia. Compressed urban living is universal, one supposes. – Ethan V. (full review)

Twittering Soul (Deimantas Narkevičius)

Not many people have mourned 3D cinema’s second waning. Yet, every now and then, the old parlor trick threatens to capture the imagination. I can think of two films in the last few years that have done such: the first cost around $400M, made about six times that at the box office, and took place on Pandora; the second is titled Twittering Soul and is the first 3D film ever made in Lithuania. It’s set in a misty rural landscape in the late 1800s, a pre-Soviet time in northeastern Europe that cinema rarely depicts. Amongst its tapestry of folklorish characters is a feudal lord with an interest in photography, which he views by holding a candle behind the image, bringing into focus this film’s visual layers. While watching, I was reminded of the doubled-image technique of stereoscopic photography that went out-of-fashion sometime in the middle of the 20th century––images that viewed today, whether in a museum or through a viewfinder, retain their transportive powers. Soul was shot by DP Eitvydas Doškus with a 3D camera, natural light sources, and mostly static shots to give that same ethereal experience: something strange and ineffable, painterly yet tactile. For a moment, it still feels like you’re really there. – Rory O. (full review)