We don’t want to overwhelm you, but while you’re catching up with our top 50 films of 2024, more cinematic greatness awaits in 2025. Ahead of our 100 most-anticipated films (all of which have yet to premiere), we’re highlighting 30 titles from this year’s festival circuit that have either confirmed 2025 release dates or await a debut date from its distributor. There’s also a handful of films seeking distribution that we hope will arrive in the next 12 months, as can be seen here.

As an additional note: a number of 2024 films that had one-week qualifying runs will get expanded releases in 2025, including Hard Truths (Jan. 10), The Last Showgirl (Jan. 10), I’m Still Here (Jan. 17), Armand (Feb. 7), and Universal Language (Feb. 14).

Pepe (Nelson Carlo De Los Santos Arias; Jan. 10 on MUBI)

Nelson Carlo De Los Santos Arias’ 2017 fiction debut Cocote was the dazzling, textured arrival of a new voice; the director doesn’t disappoint with his invigoratingly peculiar follow-up. Pepe, which premiered at Berlinale and comes to MUBI at the start of the new year, takes us inside the mind of one of Pablo Escobar’s dying hippos. Anything close to The Lion King or Dr. Dolittle, this is not, thankfully, as the director uses his ambitious conceit to explore global political strife, ecological dangers, and animal cruelty. In what would make for a great double feature with another Berlinale highlight that gave sentience to the unexpected, Mati Diop’s Dahomey, Pepe is a formally radical odyssey that’s hard to shake. – Jordan R.

Presence (Steven Soderbergh; Jan. 24)

For a prolific artist, a surge of creativity can often be synonymous with a dip in quality. Though not if you are Steven Soderbergh. He’s only continued to reinvent himself and forge ahead with new technology, subjects, and structural gambles. His latest film, Presence, is a haunting ghost tale wrapped in a nuanced family drama, and one of his most formally ambitious attempts yet. What if the camera, operated by Peter Andrews (aka Soderbergh), was the ghost? And every single shot in the film was a single take from this perspective? And, to further add to the self-imposed constraints, the ghost never leaves the house? From the very first shot, as we see the presence rapidly move through every room in the yet-to-be-sold empty house, laying the foundation for the horrors to take place, one senses Soderbergh is having a total blast with this concept. Reuniting after Kimi, David Koepp’s rollercoaster of a script is also one that doesn’t forget to flesh out its characters, making for a funny, disturbing, and nimble genre exercise that further proves Soderbergh is one of the most inventive directors to play the game. – Jordan R. (full review)

Eephus (Carson Lund; March 7)

If the perfect sports movie illuminates the fundamentals that make one fall in love with the game, there may be no better movie about baseball than Carson Lund’s Eephus. Structured solely around a single round of America’s national pastime, Lund’s debut feature beautifully, humorously articulates the particular nuances, rhythms, and details of an amateur men’s league game. By subverting tropes of the standard sports movie––which often captures peak physical performance in front of legions of adoring fans––Lund has crafted something far more singularly compelling. Rather than grand slams and no-hitters, there are errors aplenty and no shortage of beer guts and weathered muscles amongst the motley crew. Lund is more interested in examining the peculiar set of social codes that only apply when one is on the field, unimpeded by life’s responsibilities and entirely focused on the rules of the game. – Jordan R. (full review)

On Becoming a Guinea Fowl (Rungano Nyoni; March 7)

With her second feature film, Zambian-Welsh director Rungano Nyoni looks at the pain, memory, and absurdity of familial Zambian tradition. On Becoming a Guinea Fowl follows Shula (Susan Chardy), who finds her uncle dead in the middle of the road one night. Shula and her cousin Nsansa (Elizabeth Chisela) spend the first minutes of Nyoni’s film in a car, waiting for the night to end and police to arrive. Her uncle is wearing a sumo suit and has been found near the town’s brothel, making him to be a neighborhood clown acting without restraint or limitation. – Michael F. (full review)

Who by Fire (Philippe Lesage; March 14)

You’d expect the pivotal music cue in Philippe Lesage’s Who by Fire to be its namesake by Leonard Cohen, a beautiful and plaintive prayer of a song. But instead it’s The B-52s’ infectious slice of bubblegum “Rock Lobster,” initially seeded through a dialogue reference, then heard fully in an eccentric sequence I won’t further detail. The funny, noteworthy quirk of “Rock Lobster,” though, is its structurally well-earned length of just under seven minutes. Who by Fire, running 161 minutes itself, also seems to be up to something, committing to that runtime as such a contained, semi-domestic drama: a provocation through duration. – David K. (full review)

An Unfinished Film (Lou Ye; March 14)

Five years since its outbreak, COVID has shifted from a symbol of “institutional superiority” to an inconvenient embarrassment for the Chinese government. In parallel films about the pandemic also changed from “main melody” propaganda film into outright censorship; that’s why Lou Ye’s An Unfinished Film is so important. In what’s termed a “making-of” documentary, Lou creatively explores filmmakers’ role confronting both a crisis and governmental suppression, grappling with the responsibility of preserving history through cinema. – Frank Y.

Misericordia (Alain Guiraudie; March 21)

In a career spanning four decades and eight features, Alain Guiraudie has cemented himself as one of our most astute chroniclers of desire. If there’s any leitmotif to his libidinous body of work, that’s not homosexuality (prevalent as same-sex encounters might be across his films) but a force that transcends all manner of labels and categories. His is a cinema of liberty: of vast, enchanted spaces and solitary wanderers who wrestle with their passions, and in acting them out, change the way they carry themselves into the world. Desire becomes an exercise in self-sovereignty, a way of reasserting one’s independence––a rebirth. It is often said that cinema is an inescapably scopophilic realm, where the act of looking is itself a source of pleasure, but Guiraudie has a way of making that dynamic feel egalitarian, as thrilling for those watching as it is for those being watched. – Leo G. (full review)

Grand Tour (Miguel Gomes; March 28)

If Chris Marker and Preston Sturges ever made a film together, it might have looked something like Grand Tour, a sweeping tale that moves from Rangoon to Manila, via Bangkok, Saigon and Osaka, as it weaves the stories of two disparate lovers towards a fateful reunion. The stowaways could scarcely be more Sturgian: he the urbane man on the run, she the intrepid woman trying to track him down. Their scenes are set in 1917 and shot in a classical studio style, yet they’re delivered within a contemporary travelogue––as if we are not only following their epic romance but a director’s own wanderings. – Rory O. (full review)

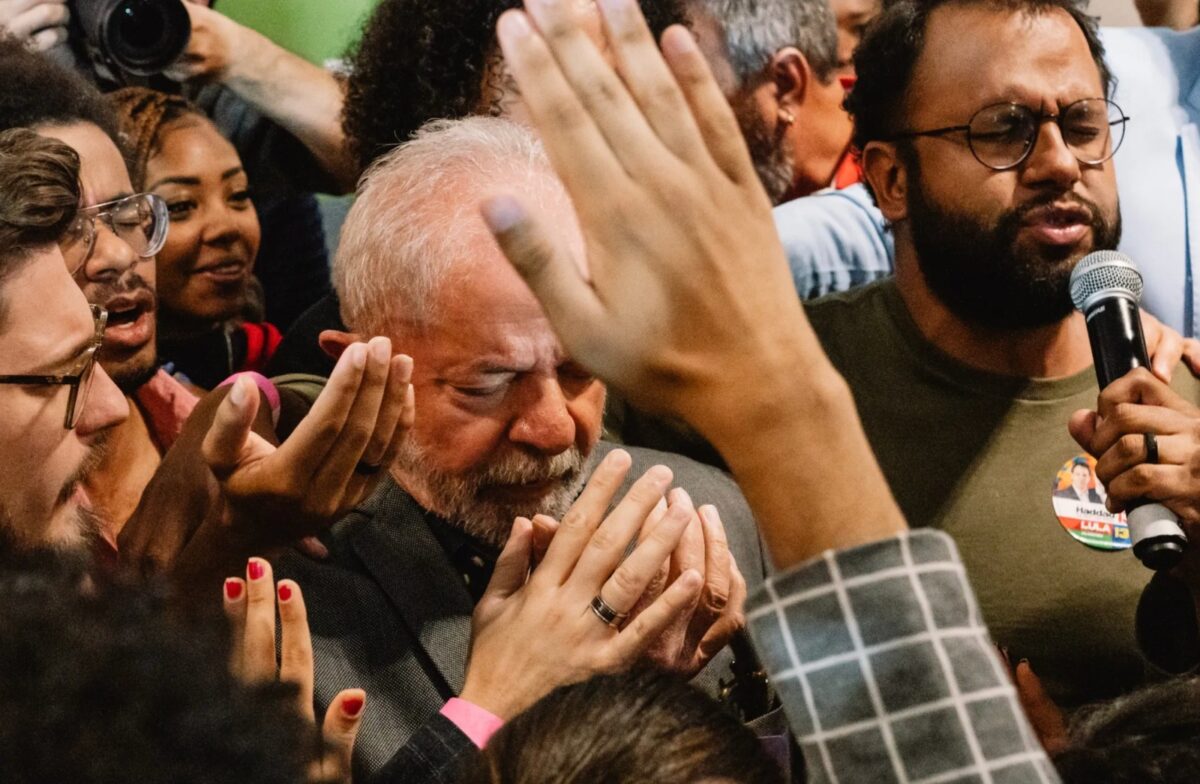

Apocalypse in the Tropics (Petra Costa)

Five years, the closest presidential election in Brazilian history, and one insurrection after her last examination of Brazil’s tumultuous socio-political sphere, Petra Costa––the brilliant documentarian behind Elena and The Edge of Democracy––hones in on Jair Bolsonaro, the radical evangelical right that won him the presidency in 2018, and the theocracy they collectively fight to instate. With Costa’s nearly unfettered access to the main characters of modern Brazilian politics, the events of Apocalypse in the Tropics practically unfold in real time––a thrilling, profound documentary horror. – Luke H. (full review)

April (Dea Kulumbegashvili)

Like Beginning, April also carries the mark of reality, mediated. The director is inspired by fictionalized stories gleaned from the real world––especially her hometown, a village at the foot of the Caucasus mountains in Georgia and its people. Beginning’s sparse dialogue, long takes, and atmosphere of violence closing in on the main character––a Jehovah Witnesses pastor’s wife played by the new film’s lead, Ia Sukhitashvili––made space thicken and swell, while April breathes. Arseni Khachaturan’s patient, somehow insistent camera uncovers a world that is both familiar and uncanny: a world split between rumbling storms, rainfall, a gorgeous sunset seen from angles almost as low as the grass itself, and a rotting patriarchal society that squashes female independence with its body politics. Nina (Sukhitashvili) is an OBGYN who, despite best efforts, has to report a newborn’s death as the result of a previously unregistered pregnancy. The local woman’s husband demands an investigation, well aware of rumors that Nina performs illegal abortions in the village––something the patriarchy cannot allow. – Savina P. (full review)

The Ballad of Suzanne Césaire (Madeleine Hunt-Ehrlich)

The Ballad of Suzanne Césaire, the feature debut from artist and filmmaker Madeleine Hunt-Ehrlich, aims to foreground its primary literary material and historical context, but instead directs more attention to its oneiric touches and environmental phenomena––the “wind in the trees,” so to speak. The title figure, together with her more widely known husband Aimé Césaire, were both at the forefront of the négritude movement, which sought to put Francophone literature by colonized peoples in greater dialogue with their African ancestry, and to depict this with a supple, surrealistic view of the world. Assembled from deep research, assistance from academic specialists, and consultations with the Césaire offspring, Hunt-Ehrlich’s bold formal schema still prevents us from fully absorbing these efforts: “feeling” does outpace our full understanding. The vibrant Caribbean music and torch songs on the soundtrack make plain it’s a ballad, not a pedagogic Lecture of Suzanne Césaire. – David K. (full review)

Bob Trevino Likes It (Tracie Laymon)

A crowd-pleasing film inspired by director Tracie Laymon’s experience talking with a stranger online at a low point in her life, Bob Trevino Likes It is a moving story that proves good people do exist in this world. With two wonderful performances by Barbie Ferreira and John Leguizamo––playing two strangers who share the same last name but are otherwise unrelated––the film progresses into a moving yet somewhat predictable affair. And that’s okay. It’s also not just a work of cinematic comfort food, with Ferreira expressing an incredible amount of emotional vulnerability, humor, and at times a youthful naivety in a performance that’s a little more complex than initially meets the eye. – John F. (full review)

Broken Rage (Takeshi Kitano)

Split into two chapters, the film kicks off as a crime thriller before switching tones altogether and revisiting the first part scene-by-scene in a more delirious light. Kitano stars in both as a gun-for-hire. Infallible in the first and hopelessly clumsy in the second, he’s “Mouse,” a hit man whose murderous routine is upended once cops recruit him to infiltrate a drug ring. Tonally distinct as they may be, humor permeates both parts. Even in the ostensibly more “serious” first, Kitano’s script moves with a childlike logic: it only takes Mouse a couple of punches in a staged brawl with another mole to ingratiate himself with the mobsters he’s been asked to spy on. His killing-machine loner is a comic riff on the other unbeatable assassins he played in the past (think of Otomo, the thug of his Outrage saga). But the commitment to poking fun at his onscreen personas is something I hadn’t seen him do since 2005’s Takeshis’, a comedy that nonetheless spiraled into self-indulgent flights of fancy. Nothing farther from Broken Rage’s spirit. This isn’t just a wildly funny film––the kind that sent people around me at the press premiere into convulsed laughter just a few scenes in––but a pointed rebuke to the discourse that saw the director’s two impulses (popular comedy and artful seriousness) as opposite poles in a magnetic field. – Leonardo G. (full review)

By the Stream (Hong Sangsoo)

If Hong’s self-repetition can cause doubt, there’s something equally reassuring seeing his two stars, Kim Minhee and Kwon Haehyo, take up space in a two-shot, their figures seen from the knee upwards. The former is Jeonim, a textiles artist and lecturer at a Seoul women’s college; the latter plays her uncle Sieon, an actor and director banished from his once-eminent career in the aftermath of a scandal (that’s only opaquely explained in the script) and now the proprietor of a bookshop in the Kangwon Province. Sieon has been called upon by her adoring, seldom-seen niece to, proverbially, recover his sea legs: he has to devise an informal skit for her Western Art class to perform at semester’s end, after the previous director (Ha Seongguk, incarnating youthful folly in recent Hongs) also exited the troupe in disgrace. And we know the “why” more starkly: he “separately” dated three members of the group, who all dropped out in solidarity. – David K. (full review)

Caught by the Tides (Jia Zhangke)‘

Jia Zhangke’s is often a cinema of déjà vu: “We’re again in the northern Chinese city of Datong,” Giovanni Marchini Camia wrote for Sight and Sound back in 2019, “it’s again the start of the new millennium, Qiao is again dating a mobster, yet no one else makes a reappearance and there are enough differences to signal that this isn’t a sequel or remake.” Camia was writing about Ash Is Purest White yet much of the same could be said for Caught by the Tides, the director’s latest experiment in plundering his archive––indeed his memories––and spinning what he finds into something new. The protagonist of Tides is again named Qiao and is again played by Zhao Tao, appearing here in more than 20 years of the director’s footage and allowing the viewer to watch that singular creative partnership evolve in real time––one of the great treasures of contemporary cinema. – Rory O. (full review)

Drowning Dry (Laurynas Bareiša)

Memories can be slippery things. Take what happens around the halfway point of Laurynas Bareiša’s beguiling second feature: two women––more specifically Ernesta (Gelminė Glemžaitė) and Juste (Agnė Kaktaitė), sisters on holiday with their respective families (a husband each, with one son and one daughter, respectively)––start dancing to Donna Lewis with what looks like an old routine, part half-remembered movements, part muscle memory. This entrancing sequence is cut short when their kids ask to go swimming, where one of the children appears to drown. The film then jumps forward in time, where Ernesta is visiting a man whose life was saved by one of her late husband’s organs. Before finding out how he died, we jump back again: same holiday, same sisters, same dance, only this time it’s Lighthouse Family. “When you’re close to tears, remember,“ Tunde Baiyewu sings, “someday it’ll all be over.“ – Rory O. (full review)

Familiar Touch (Sarah Friedland)

In a sunny kitchen in California, Ruth prepares a sandwich with the muscle memory that only a lifetime allows. Bread is toasted and left to cool; dill is picked and chopped efficiently; sour cream, radish, and salmon are arranged to resemble a blooming flower. After going to get ready, she serves it to a man named Steve (H. Jon Benjamin) who she doesn’t seem to recognize. When he tells her he’s an architect, she responds, “My father builds homes. Maybe you’ll meet him one day.” Caught off-guard, her son can only offer a loving smile and say “I’d like that.” This uncertain space––part clarity, part blur––is the subject of Sarah Friedland’s moving debut feature Familiar Touch. – Rory O. (full review)

Friendship (Andrew DeYoung)

The level of enjoyment audience members will have with Andrew DeYoung’s Friendship is tied directly to their tolerance for the humor of Tim Robinson. The star of the meme-inspiring Netflix series I Think You Should Leave has cultivated a devoted following by creating situations of embarrassment and characters who veer wildly from absurdist rage to complete self-delusion. (See the infamous “we’re all trying to find the guy who did this” meme.) In my mind, I Think You Should Leave is the funniest series of the last decade or so. While Robinson’s full-length feature as star does not reach his show’s highs, it’s still a hysterically funny, pitch-black comedy. – Christopher S. (full review)

Ghost Trail (Jonathan Millet)

The wars in Gaza and Ukraine have dominated headlines for the past several years, yet receiving relatively little coverage today is the Syrian civil war, sparked in the wake of 2011’s Arab Spring. It is yet ongoing and stands now at an uneasy stalemate. Over a decade of fighting, horrifying humanitarian and war-time crimes were committed; all the while 13 million Syrians were displaced from their homes. These refugees, lost in foreign countries offering asylum, are still looking for answers and perhaps a reckoning and retribution. Director Jonathan Millet’s debut narrative feature Ghost Trail dives deep into one survivor’s psyche and lays bare the cost of a conflict from which the world seems to have moved on. – Ankit J. (full review)

Happyend (Neo Sora)

“Something big is about to change,” is surely one ominous beginning for a debut fiction feature, but director Neo Sora knows how to calibrate the fine balance between anticipation and inevitability. A story set in the near future, Happyend makes Tokyo a vast playground to high-school seniors gathered around childhood pals Yuta (Hayato Kurihara) and Kou (Yukito Hidaka). Life is blooming and the future is ripe for those teenagers, even if the whole city is constantly preparing itself for a catastrophic earthquake. Daily drills and false alarms interrupt an otherwise-smooth rhythm where Yuta and Kou gather their classmates at their Music Research Club, an extracurricular that’s more enjoyable than practical in purpose. With a fully equipped school room at their disposal at all times, the gang can build a secure microcosm for the shared love of electronic avant-garde and a generally good time. – Savina P. (full review)

Horizon: An American Saga – Chapter 2 (Kevin Costner)

How blessed are we to have a whole six hours of Kevin Costner’s mythopoetic Horizon already make their way to (some) audiences, especially when this project has been on his wish list since 1988? I often try to demystify festival viewing experiences by supplying an honest, sometimes critical lens through which a reader can see the cracks in their glossy surfaces. Nevertheless, in the case of Horizon: An American Saga – Chapter 2, I’d own every bit of privilege that brought me to its Venice premiere––in a rather small venue, on the very last afternoon, with little fanfare––not least because Costner’s multi-chapter saga is so difficult to see on the big screen. It’s not just the scale of storytelling or the fact that the Hollywood legend sponsored a huge chunk of its production himself, not the runtime and two more planned installments to (hopefully) come––it’s the dedication to cinema as a place for genuine connection, both between the characters onscreen and between audience and film. – Savina P. (full review)

On Swift Horses (Daniel Minahan)

It’s been some time since we’ve had such a ridiculously attractive lineup of buzzworthy young actors as the quartet starring in Daniel Minahan’s On Swift Horses. Daisy Edgar-Jones, the tremendously talented star of Twisters and Normal People, is Muriel, a young woman in 1950s Kansas. Her soon-to-be husband, Lee, is played by Will Poulter, who has shined in everything from Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 3 to Kathryn Bigelow’s underrated Detroit. Returning from Korea––and making his introduction to Muriel shirtless, reclining on a car––is Lee’s brother, Julius. Yes, friends: the devil-may-care Julius is played by Jacob Elordi. I have not even gotten to the characters played by Babylon’s Diego Calva and Sasha Calle, a.k.a., the best thing about The Flash. – Christopher S. (full review)

Pavements (Alex Ross Perry)

If the Hollywood superhero-industrial complex is perishing, the Rolling Stone and Spin magazine extended universe is hastily being built. What better defines “pre-awareness” for the studios like the data logged by Spotify’s algorithm, where billions of track plays confirm what past popular music has stood the test of time, and also how––in the streaming era––you can gouge ancillary money from it? But unlike the still-brilliant Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story, which stood to excoriate the nostalgia sought by such films, recently reinvigorated by the success of Bohemian Rhapsody, Alex Ross Perry’s Pavements, on the eponymous ’90s slacker idols, justifies that every great band deserves a film portrait helping us to wistfully remember them, and also chuckle as pretty young actors attempt to nail the mannerisms of weathered, road-bitten musicians. So good luck, Timothée. – David K. (full review)

The Shrouds (David Cronenberg)

David Cronenberg’s films have often imagined a future where technology would find a way into our collective id. 55 years into the director’s incomparable career, might that future have finally caught up with him? In Cronenberg’s new film––the slick, scrambled The Shrouds––there are two barely speculative conceits: that an AI chatbot could be designed to look like a recently deceased love one; and primarily, that a company might have the bright idea to wrap a blanket of HD cameras around our nearest and dearest before they’re sent six-feet-under, allowing us to check in on their decaying corpse, all with the click of an app. – Rory O. (full review)

The Sparrow in the Chimney (Ramon Zürcher)

There’s something electrifying about watching a filmmaker break free from well-worn formulas and push themselves into new, uncharted territory. The Sparrow in the Chimney, Ramon Zürcher’s third feature, is the final installment in a trilogy of highly flammable chamber dramas. Anyone familiar with the previous two, 2013’s The Strange Little Cat and 2021’s The Girl and the Spider––the latter written and directed with twin brother Silvan, who’s produced all his sibling’s projects––will likely remember the clash between their austere mise-en-scène and the tempestuous conflicts that coursed through them. Captured in largely static shots among contained locales (an apartment, a house) and timeframes (Cat spanned a day, Spider two), the films suggest exercises in geometry whose immaculate compositions are always on the verge of collapsing. Pushing against their steely facades are family feuds, acts of wanton cruelty, and violence; watching them, the tension at times is so unbearable you’re left crouching in anticipation for the frame to burst. – Leo G. (full review)

Stranger Eyes (Yeo Siew Hua)

In a film so concerned with our current media regime––the way we produce and consume images of each other––Lee saunters into Stranger Eyes as a kind of anomaly. There is a stark contrast between the surgical eyes of CCTV cameras and the actor’s own, the way surveillance devices capture reality and how Lee’s Wu processes it. I do not mean to downplay Wu and Panna’s turns. The former in particular channels a feverish angst, and his transformation from object of Wu’s obsession into voyeur himself largely works. But Stranger Eyes belongs to Lee. Whether or not Yeo wrote it with him in mind, I can’t think of a better performer to flesh out the chasm that powers the film: between different ways of looking, between fears as old as time itself and the state-of-the-art technology used to bring them to light. – Leonardo G. (full review)

The Surfer (Lorcan Finnegan)

In The Surfer, an exploitation film set to pressure-cook, a mild-mannered man is pitted against a group who even Andrew Tate might find a touch extreme. It’s set in South Australia on fictional Luna Bay, the kind of place where if the heat doesn’t get you, something else probably will. The water shines turquoise-blue but the beaches look like scorched earth. Into this furnace arrives an unnamed man (Nicolas Cage) hoping for nothing more than to view a cliffside property and catch a wave, but the locals have other ideas: “Don’t live here, don’t surf here,” one says, offering about as much hospitality as a switchblade. – Rory O. (full review)

Tendaberry (Haley Elizabeth Anderson)

A soulful coming-of-age story with far more on its mind than the here and now, Haley Elizabeth Anderson’s Tendaberry is an ambitious directorial debut mixing various storytelling forms to achieve its poetic patchwork of ideas. Combining recollections of the past, a present way of life, and hopes for the future through the eyes of 23-year-old Dakota (Kota Johan), it follows her journey juggling romance, work, friendship, and family. The nature of its scattershot hybrid approach––incorporating narrative, documentary, and archival materials––results in certain passages feeling a bit stretched, but the cumulative effect is one of an impressive new voice. – Jordan R. (full review)

Vulcanizadora (Joel Potrykus)

Like the punk-rock cousin of Kelly Reichardt’s Old Joy, Joel Potrykus’ Vulcanizadora also concerns a voyage in the woods that pinpoints the exact moment an old friendship abruptly dies. The film also represents a maturing-of-sorts for the Michigan-based provocateur, revisiting characters first introduced in his 2014 film Buzzard and a few themes explored in his lesser-known 2016 feature The Alchemist Cookbook. Like many artists shifting from early to mid-career, Potrykus explores themes of having a family––or, in this case, abandoning it––while still retaining the edge present in his nascent works. It suggests a conundrum of sorts, but while other indie filmmakers start small and work towards scaling-up, this filmmaker refreshingly hasn’t. (His 2018 masterpiece Relaxer took place in the corner of an apartment, rather than expanding his slacker universe). – John F. (full review)

You Burn Me (Matías Piñeiro)

With his latest feature, Matías Piñeiro playfully, gorgeously adapts “Sea Foam,” a chapter in Cesare Pavese’s Dialogues with Leucò. Centered around fictional dialogue between the ancient Greek poet Sappho and the nymph Britomartis, played by Gabi Saidón and María Villar, respectively, Piñeiro’s latest is a feat of effervescent poetic beauty, melding poignant words with stunning images to a a dizzying, transcendent effect. – Jordan R.

Việt and Nam (Trương Minh Quý)

The opening shot of Việt and Nam, writer-director Trương Minh Quý’s sophomore film, is a feat of cinematic restraint. Nearly imperceivable white specs of dust begin to appear, few and far between, drifting from the top of a pitch-black screen to the bottom, where the faintest trace of something can be made out in the swallowing darkness. The sound design is cavernous and close, heaving with breath and trickling with the noise of running water. A boy incrementally appears, walking gradually from one corner of the screen to the other. He has another boy on his back. A dream is gently relayed in voiceover. Then, without the frame ever having truly revealed itself, it’s gone. – Luke H. (full review)

More to Recommend

- 7 Walks with Mark Brown

- All of You

- The Assessment

- The Damned

- Daniela Forever

- DIG! XX (Jan. 17)

- The Empire

- Every Little Thing (Jan. 10)

- Gazer (Feb. 7)

- Little, Big, and Far

- Paddington in Peru (Feb. 14)

- There’s Still Tomorrow

Continue reading: The 100 Most-Anticipated Films of 2025