What if it was an established fact that free will as a concept was dictated by our body’s chemistry? Every decision we think we’re making is really made implicitly by our organs — more correctly, they are dictating to our brains what it is we want. That shopping spree for things you don’t need? That affair with someone you don’t even like? You can’t control either impulse if you truly wanted to because your hormones and biological imperatives in those specific moments have forced your hand. Just think about the sheer chaos that would ensue from such a revelation. You could connect every horrible act you’ve ever committed to some bit of undigested beef (as Ebenezer Scrooge would say). And while under such duress, your body couldn’t stop itself.

It’s a perfect science fiction premise that sprawls to include memories and vision — both incomplete extrapolations wherein our body’s chemistry fills the blanks as it sees fit rather than as reality dictates. The problem Peter Schønau Fog runs into while using it for his film You Disappear is that it’s not science fiction. His film — based on the novel by Christian Jungersen — is conversely a straightforward reality-based drama with non-linear cuts cobbling past and present together in order to play with our preconceptions of what’s seen. And the idea of chemistry controlling free will isn’t some futuristic concept either. It’s a product of Frederik Halling’s (Nikolaj Lie Kaas) predicament, a principal who’s embezzled his private school into bankruptcy while under the influence of an orbitofrontal tumor.

As his lawyer (Michael Nyqvist’s Bernard Berman) argues in court — the trial takes up about a third of the runtime despite being interspersed throughout a collage of scenes pre-diagnosis and post-diagnosis — Frederick was cognizant of his actions, but acted without criminal intent. He tells the judge alongside psychological corroboration that the tumor stopped Frederick from seeing why investing the school’s money without telling anyone was wrong. His impulse was born from the excitement of doubling their budget, building a new wing, and surprising his friend and boss Laust Saxtorph (Lars Knutzon) in the process. This man who was a workaholic with barely enough time to say goodnight to his wife (Trine Dyrholm’s Mia) and son (Sofus Rønnov’s Nicklas) was now suddenly smiling with his foot on the gas.

I say this literally as the film opens with the trio driving on a winding mountain road while on vacation abroad. Nicklas eggs his father on to drive faster and Frederick complies despite Mia’s abject horror. They almost mow down cyclists and do sideswipe the rocky façade before Nicklas joins his mother in screaming for him to stop. It’s the adrenaline rush high that he cannot control, his frustration in not doing anything right in Mia’s eyes, and the tumor in his head that causes a seizure and a tumble down the cliff. The ensuing MRI finds the blockage, his doctors back home explain how it could affect his mood and psychology, and he’s arrested shortly after getting it removed. The question is when the tumor changed him.

Better yet: did the tumor change him? You can’t help wondering if his whole defense is a ruse to avoid jail time much like the prosecutor (Mikkel Boe Følsgaard) believes. And since the film isn’t from Frederick’s perspective, it’s nearly impossible to know. We receive Mia’s account of everything instead, accompanied by psychobabble narration I must admit wasn’t easy to blindly digest. While Fog moves back and forth through time without any captions to concretely situate us — eventually splicing Bernard’s own tragic ordeal with his wife Lærke (Meike Bahnsen) to the mix too — Mia starts regurgitating everything she’s read about what it is that makes a person. You Disappear quickly spirals out of control from one victim of brain trauma to a support group to the entire world.

Not only does Mia begin reevaluating her marriage and the crazy things Frederick did before the tumor, with the tumor, and after the tumor — everyone else wonders if they’re responsible for their own misdeeds too. It starts small with Nicklas misinterpreting handouts left around the house, believing that he’s allowed to act like a jerk because he’s only fifteen and not yet emotionally mature enough to wield his adult intelligence. Then it grows larger with a potential affair brewing between Mia and Bernard despite the main takeaway from the latter’s car crash that crippled his wife being a rigid sense of fidelity. Nonsense is laughed off as chemical reaction and the chaos Mia warned her son a world without consequences breeds arrives. And it almost works.

I say “almost” because Fog decides to change reality as though another truth was always there. But it wasn’t. He doesn’t merely rewind to show us events from a different angle — he shows them from a completely different reality. I like the idea that we shouldn’t trust anything we see or hear because our brain is fooling us ever so slightly, but that’s not the case when the filmmaker is the one purposefully doing the fooling. The most unfortunate result of this too-easy shift is that the person we rooted for as the victim is made into the predator. All this time we have begun to despise one character for mind games and lack of remorse when it should have been the other? Sorry. I don’t buy it.

I could deal with the disjointed narrative and non-linear delivery because I actually started enjoying the game of figuring out where we were on the timeline before events proved it. I embraced the conceit of Frederick not being of sound body and mind, especially with the unique twist of having him become more pleasant and compassionate with the tumor rather than less. But turning the entire film into a red herring for a revelation that doesn’t land due to an unearned pivot that’s only logical if you void everything you thought you knew is where I draw the line. It’s not smart or inventive as much as lazily deciding to flip everything (one character’s innocence to malice, another’s sanity to delusion) because your plot wasn’t packing enough punch.

The acting’s great and perhaps exacerbates my dislike of where things go. Kaas expertly makes us hate and sympathize with him simultaneously as Dyrholm’s portrayal of the dutiful wife moves from repressive pushover to strong-willed woman standing her ground so as not to be dismissed as hysterical — her emotions and memories things that should never be discounted. Fog’s (and assumedly Jungersen’s) desire to “shock” with his conclusion, however, forgets to acknowledge how it also minimizes both these characters as damaging stereotypes. This could have been an intriguing look at cause and effect with an ill man’s intent on trial, but it ultimately becomes another demeaning representation of women as hyperbolic and untrustworthy. Frederick is the lover and Mia the self-centered materialist? How the heck did we get there?

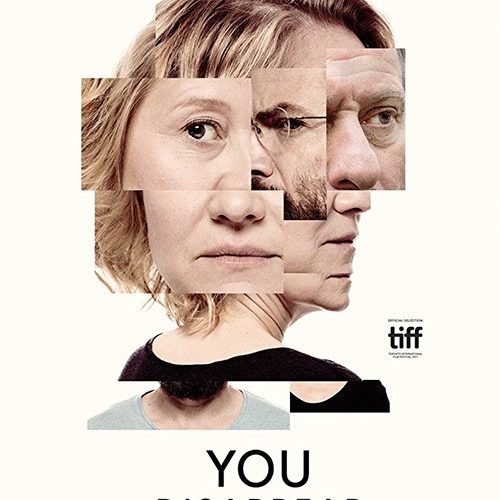

You Disappear premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival.