Sofía Hernandez (Ilse Salas) has everything: three children she can ignore, servants and maids to take care of her every whim, and a husband (Flavio Medina’s Fernando) who inherited his wealth from his father and still has yet to really work for it thanks to Uncle Javier (Diego Jáuregui) managing things like he always had. Theirs is a charmed life of opulence and excess wherein they can afford to treat aristocratic etiquette and tradition as sacrosanct while “new money” commoners try to enter their social circle as though they are animals just arrived from the wild. Sofía and Fer are practically European by contrast, propping up their Mexican backyard with class and grace. All that could make life better is Julio Iglesias serenading some “Happy Birthday” magic.

Unfortunately for them, writer/director Alejandra Márquez Abella ensures their false sense of financial security crosses paths with Mexico’s 1982 economic crisis. So rather than Spain’s favorite son gracing her mansion with an impromptu concert, Sofía’s guest of honor is a black moth that flew into their living room uninvited to take root on the wall. It’s there when Javier gives Fer his resignation and a not so confident “good luck” staying the course while American investors back out of a lucrative deal because the value of the peso was decimated. It’s still there when Sofá’s staff sheepishly tells her they haven’t been paid in a week. And it remains until so much has happened that she refuses to let it linger, killing it with a pool skimmer instead.

Why is this happening to her? As the title states, she and her friends are The Good Girls. They dote on their husbands, host elaborate parties, and shop with infinite lines of credit all while basking in their superiority over everyone else in town. Sofía just wants to play tennis with Alejandra (Cassandra Ciangherotti), play nice with newcomer Ana Paula (Paulina Gaitan) and her husband Beto’s (Daniel Haddad) “quaint” fortune, and play queen in her home. This doesn’t mean she’s some trophy wife who doesn’t understand what’s happening, though. She listens to Javier’s warnings and fears what’s to come despite painstakingly pretending nothing’s amiss with the community. Only when others start dropping like flies does she realize appearances can no longer hide the truth.

Abella crafts this fall from Mt. Olympus with expert precision and nuanced detail. A morning shortly after the news arrives sees Sofía waking alone in bed before passing a window-washing maid who’s much shorter in temperament than usual upon explaining how Fer was asleep in his home office. We don’t think much of it at first. Who cares if a maid is grumpy? So what if Sofîa asks her what’s wrong with pointed intent? It’s their right and duty respectively. Only when Sofía finds Fer and chastises him about going to his actual office so as not to scare the help into thinking something’s wrong by staying home all day do we recognize just how delicate this ecosystem is. And the scrutiny gets even worse amongst her friends.

This is unavoidable since what’s happening to her is also happening to them. Some have it worse with rumors of suicide while others hope to get ahead of the inevitable. It’s almost an overnight switch when Alejandra distances herself from Sofía to orbit Ana Paula instead. Suddenly the ones who weren’t good enough are the center of focus while those who lorded over the rest can’t earn an invitation through the door. What’s even wilder, though, is how much of a death grip Sofía has on her image and status. The world is quite literally falling down around her and yet she’ll still be scheming until the bank changes the locks on her house. While the others evolve, she remains haughty — that identity proving all she’s ever had.

It’s an intriguing look behind the curtain as she deflects and distracts her employees, store clerks, and even her quizzical children wondering if they’re “poor.” Fer can be seen in the background disheveled and drunk, sleepwalking through the chaos without any power to rise again while Sofía is forever moving forward despite the cracks in her pristine façade growing larger by the day. And Abella isn’t averse to drawing this situation humorous in its absurdity. She wants us to pity Sofía as much as bask in her comeuppance. To go from earnestly telling her children not to make friends with any Mexicans at summer camp to being told by Alejandra that she isn’t obligated to go to anymore parties while not quite “looking herself” is quite the plummet.

So we laugh at the hubris, hypocrisy, and stunning reversals perpetually on display. Since Sofía guides us through the turmoil, we experience her entitlement and devastation upon discovering her social position irrevocably changed with extreme force. Salas is brilliant in the role moving from unbothered to anxiously scratching a rash onto her neck. The tenacity she shows when the deck is stacked against her and under hardened concrete would be commendable if it wasn’t already so tragic. But while she often confirms how ingrained in her ways she is by not being able to switch allegiances as a means of survival, there come a time for everyone when “if you can’t beat them, join them” sentiments take over. Sofía might even become human by the end.

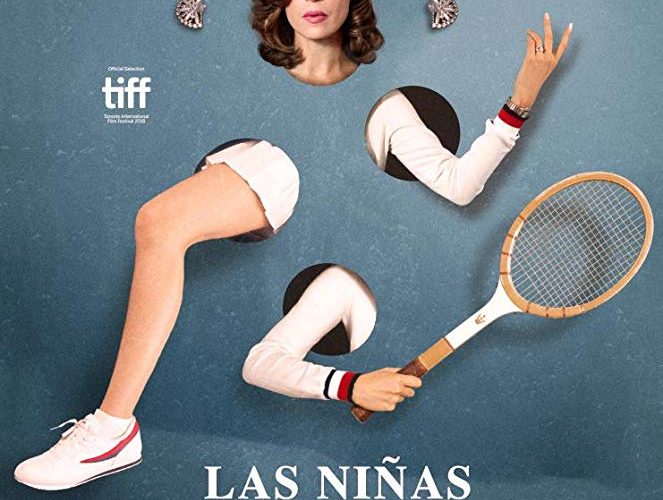

The Good Girls premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival.