A text against a black screen informs us of the Ta’ang ethnicity belonging to Myanmar, a nation engulfed in an endless civil war, which happens to be driving its citizens, chiefly this group, out. Crossing the border between their home and China, the Ta’ang refugees are in a constant state of displacement, if still unity. Though if deceived by this simple, prosaic way of dosing out information to the audience, which will likely consist 95% of bourgeois festival attendees, a counter is swiftly served. Its first real image is one of violence, both in form and content; what appears a father striking a child, like a camera suddenly, and ungraciously, emerging out of thin air, as if birthed into this dire situation as an uneasy necessity for what seems an emergency.

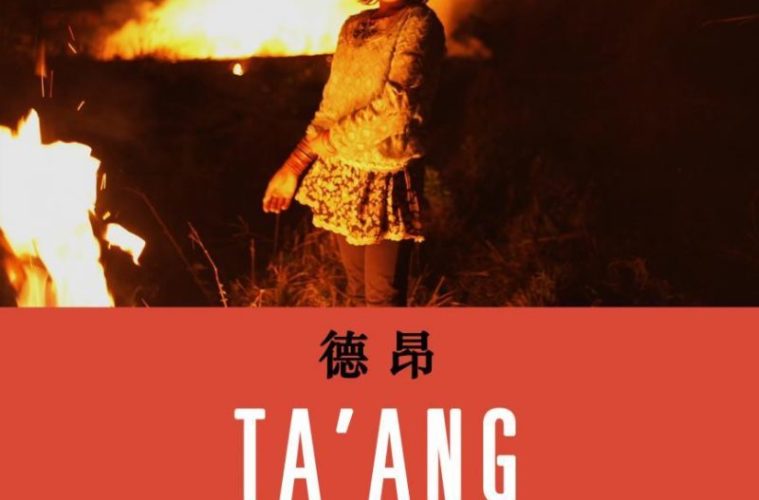

That being said, there’s a lack of didacticism from Ta’ang, it almost initially seemingly like an excuse to capture the texture of their environment, beyond just the makeshift lives in tents; be it the mud they trudge through, the bamboo they chop or the fire they gather around at night. (A glare into the camera from one of subjects as she’s lit by the dint of flames is immortalized by the film’s chief publicity still.) With director Wang Bing‘s penchant for capturing the human relationship to nature, one could only imagine what he would do with a fictional film, perhaps a western. But his continuing dedication to subjects so underrepresented feels genuinely important, even within a niche of art cinema that so favors depictions of poverty.

The film doesn’t necessarily go about identifying characters amongst the on-the-move groups we see — even when one arrives in an urban environment like the Chinese city of Nansan with little opportunity, we don’t see them further. What soon follows is somewhat of a rupture with which we can still discern as a different set of people, at this point articulating the war they’re fleeing from far more explicitly. They’re essentially the ones in the shadows, standing around as they hear the sound of jets and bombs. The difference comes in the lack of portraying dead bodies; there’s no exploitation on hand. There’s a sequence in which the camera trails to a little girl trying to make her younger sister laugh while the sound of dropping bombs blare in the distance. This seems like the entire point of the film: not distracting us from the situation, but articulating the spontaneous humanity within it.

This writer strangely thought of a motif of Brian De Palma while watching the film: the masochistic relationship we hold with cinema, in our failure to seemingly save someone, to reach through the screen and divert them from the doomed path they’re on. Though that’s to ascribe a kind of pity, or even distance, to Wang Bing’s intentions, which seems the anthesis. Yes, as said before, an emergency is on had, but not necessarily a tragedy. The motivation isn’t the supposed good left-wing values of acknowledging suffering or informing the privileged, but to create its own, living, breathing, cinematic world of people marching through.

Ta’ang screened at the Toronto International Film Festival.