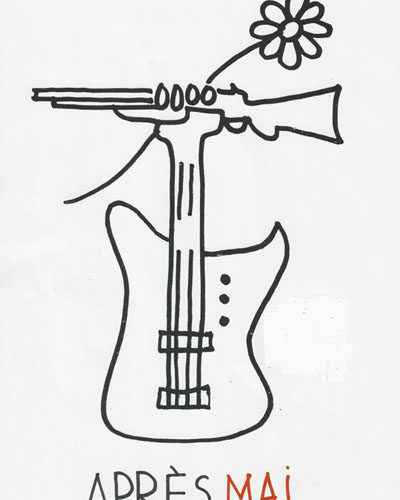

Sex, drugs, art, and revolution — such was the life of a young European in 1971. Or at least it was the life of a young director at 17 trying to reconcile the state of his country and his ambitions for the future. Taking us along for the rapid ascent into adulthood of a group of school-aged French radicals, Olivier Assayas‘ semi-autobiographical film Something in the Air (Après mai) is a slice of life at a time of wholesale liberation. These Trotskyites look to dissolve the government’s ‘Special Brigades’ and win student rights through pamphlets and graffiti, their actions’ consequences escalating while their political bent begins to wane. There’s nothing like growing up to put an end to youthful idealism.

Gilles (Clement Metayer) is the epitome of boutique rebel, carving an ‘A’ for anarchy on his desk and listening to Syd Barrett while painting. A prospective artist, his dreams are easily pushed to the side when the needs of the ‘party’ are brought his way. So dedicated to the cause are he, Christine (Lola Créton) and Alain (Felix Armand) that they need to escape to Italy while charges for assault are brought down upon an innocent cohort in Paris. It’s here where enlightenment strikes, philosophical changes are made and life takes them onto a new journey into the unknown. Lovers are met and lost as careers replace dreams and compromise becomes the force driving them forward.

Bohemian and hippie lifestyle is on full display as love is made into an easily malleable concept transferrable when convenient and strangely devoid of its usual crippling sorrow when lost. Infused into the sexual revolution, their intimate partners become treated the same as business and ideological ones. There are no hard feelings because each is writing their own futures — no one selfish enough to tie another down when life calls them elsewhere. Their paths will intersect again down the line, but until that time they are free to learn, experience and enjoy autonomously. Not every choice will be an ideal one, but each will teach them something new.

An international revolt, one of the film’s best aspects is its ability to show how universal the era’s upheaval was. Alain falls for an American flower child as Christine aligns with an Italian documentarian crew. Only Gilles finds himself stuck needing to return home for some semblance of balance. Between revisiting an old girlfriend (Carole Combes’ Laure), applying to art school, honing his drawing skills, and arguing taste with his father, this young man is lost in an ideal he is unsure of how to attain. Is commercial work against his ethical code? Should he only be working to shed the light on worldly travesty?

Possessed by an abundance of questions and choices that will alter their trajectories, Assayas seems content to simply show life evolving without caring for any specific end game. Plot therefore has little bearing while progress means everything. These kids find joy a tenuous concept and grow into their earlier lofty politics through experiences that show what matters and what were simply the idealistic fantasies of naïve children rebelling purely for the sake of the fight. Adolescence hasn’t changed much in the past four decades, only its circumstances. We still face oppression, war, and divergent policies; we still protest, vandalize, and do whatever is necessary to make our voices heard.

The film’s form takes a naturalistic approach, sweeping through scenery to linger on characters as they evolve. Gilles is the main focal point, but that doesn’t mean we don’t have a chance to see Alain’s tumultuous love or Christine’s existential crises. Updates on Laure and even the aforementioned innocent cohort—who remains fighting on the political frontlines—come through to tie loose ends and give Gilles more to chew on. In fact, the glorious return of Laure inside a life of depravity and heroin-idled artists might be the finest piece of the whole. Watching the mighty fall into the abyss of pleasure is a nice change of pace from the otherwise optimistic look portrayed and her story line’s conclusion amidst licking flames of possible rebirth against blaring rock music is quite unforgettable.

But besides some fantastic interludes and the stellar performances from a youthful yet poignant cast, I felt distanced from the message and therefore shut out from the film. I’m positive it will speak to those like the director who grew up in this world and sure it represents the climate and attitudes born and molded in the chaos. For myself, however, its lack of a narrative besides the general culture itself made me continuously ask myself when the point would arrive. I know I missed it and I know that’s my own ignorance’s fault, but I guess that’s the crux of subjectivity. I really hope the majority of viewers can find more to love because what does work deserves it.

Something in the Air is screening at TIFF.