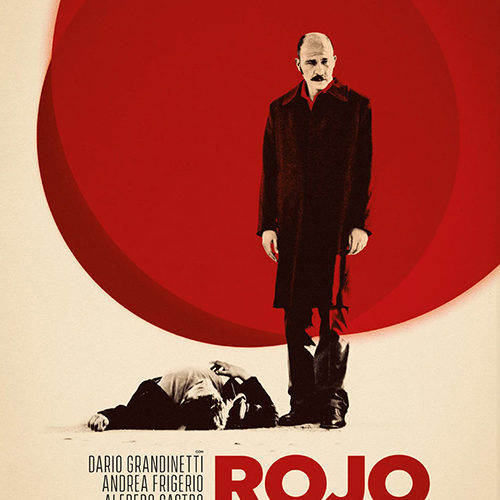

Rojo opens as people leave a house with objects in-hand, the assumption being that they were bought in an estate sale or pilfered before one could begin. A man (Diego Cremonesi) looks in the front door as clueless as we are to what’s happening before a jump cut finds him entering a packed restaurant. Impatient by the bar, he gruffly asks a gentleman seated alone (Dario Grandinetti’s Claudio) if he’s done eating. An argument colored by entitlement and false manners respectively breaks out until chaos reigns supreme. It’s a wild, disorienting scene culminating with the credits above silent scenes of calm in the aftermath once Claudio’s wife (Andrea Frigerio) arrives. Two gunshots and a trip to the desert later ready the real drama to commence.

Or do they? With a quick restart three months later, Benjamín Naishtat’s Rojo acts as though nothing occurred. We watch Claudio engage with clients (he’s the lawyer within this Argentinian community), his family, and friends. We take a glimpse into his daughter’s life with her dance team practicing their routine and her horny boyfriend’s jealousy. There’s even get a black and white commercial cutting in for extra levity out of nowhere. Eventually the husband of Claudio’s wife’s best friend enters with a proposal to acquire the now abandoned house from the start and an art show breakdown sparks the arrival of a famous television detective (Alfredo Castro) asking invasive and linguistically convoluted questions. Suddenly it’s difficult to tell what’s important, if anything, besides Claudio’s dangerous secret.

In the background of everything is a potential government coup with a federal “interventor” assigned to their Provence. Some politics are spoken in passing, but they seem more of an implicit detail that I as an American unversed in Argentinean history couldn’t begin to fully comprehend. As more and more vignettes start and stop with seemingly little bearing on the central suspense circling Claudio and the fate of the angry man from the first scene, it’s easy to guess crucial metaphor we’re being missed. This reality allowed some confused laughter to enter the theater. Is this town a hotbed for murder with bodies dumped in the sand? Or is the nation’s uncertain turmoil simply letting tempers rise and immorality flourish?

I honestly haven’t a clue. All I can say is that Castro’s private investigator enters as an adversary to Claudio — the two perpetually stuck in a stalemate of stoic glances and measured words that feel intentionally comedic by delivery. This dynamic comes to an underwhelming head — not because it’s unsatisfactory, but because the numerous plot threads surrounding it are rendered more interesting in their seeming randomness. The fact they’re more or less left hanging only amplifies that intrigue until we’re anticipating a nonexistent payoff. It’s impressive that Naishtat would let everything else exist in apparent complexity for insiders, but insanely frustrating insofar as leaving international audiences in the lurch. By the end the only certainty is that Naishtat is showing us a veritable lawless South American Wild West.

This will be enough for some. Despite feeling as though I was treading water throughout, my investment was never in question. The odd slow-motion sequence during the opening credits and the many unprompted conversations like that between Claudio’s friend and an older woman sunbathing in the backyard of the ownerless house around the mid-way point or his daughter’s boyfriend and a mutual acquaintance getting heated towards the end all possess the tension-fueled trappings of the type of film Rojo wants to be even if they never gel together into a cohesive whole. The summary itself is unsure of the rest too considering it describes Castro’s arrival as putting a wrench in Claudio’s “perfect life.” He doesn’t enter until act three. To simplify so thoroughly conjures even more mystery.

I find myself asking so many questions. What does the empty house and its legal red tape say about Argentina and the coup? Does the eclipse Claudio’s family experiences on vacation represent takeover? Blood? Do we watch his daughter’s boyfriend try to take advantage of her because his entitlement says something about the time or simply because it infers upon his later jealousy — itself the impetus for an event that’s implied but never confirmed soon after? Here I was ready to watch a man’s life unravel as a detective pokes around and I received so much more for better or worse. And while the ramifications and connections that spring from the opening prologue’s cliffhanger feel conveniently drawn, they still got me inching to the edge of my seat.

So I have to label Rojo a success even if on a purely reactive basis. I was entertained and perplexed in a way that seemed intentional — my confusion a result of Naishtat giving his audience the credit to read into things with their own historical and political interpretations. Not being that audience means I can admit the film didn’t work for me personally while also lauding its craft. The acting is strong, the visuals steeped in 70s thriller aesthetic solid (that opening credit sequence reminding me of Carrie and the constant use of split diopter points to an obvious Brian De Palma influence), and the secrets increasing in number without any truly being revealed beyond those involved a bold maneuver to ratchet up suspense without allowing any release.

Rojo premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival and opens July 12.