Films about addiction can be tough to endure depending on how authentically harrowing the experience is drawn. They can only end in one of two ways: death or sobriety. The former can be literal or figurative depending on how deep the drug of choice has its claws fastened and the latter can often be shown as a victory rather than a small step in a series of steps that will go on forever. A character’s journey is therefore always repetitive since reaching bottom before the climax only tips his/her hand too soon. But we should get to know these people and learn to care about their plight instead. We need to conjure sympathy for them or else the impending danger is little more than means to an end.

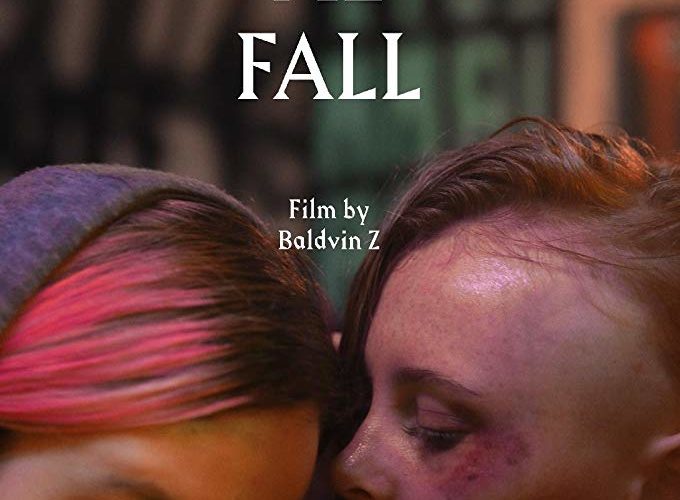

Suffice it to say, seeing that Baldvin Zophoníasson’s two-plus hour Let Me Fall was just such a film had me worried. That’s a lot of time to spend watching Magnea (Elín Sif Halldórsdóttir) and Stella (Eyrún Björk Jakobsdóttir) ruin their lives for the thrill of drug-fueled pleasure. It threatens a steady stream of unkept promises and even more betrayals as the two grow closer despite the need for their next hit always risking to come in-between them. But while this is how the film starts — fourteen year-old Magnea skipping school to run shakedown schemes for money with Stella and her boyfriend Toni (Sigurbjartur Atlason) — Zophoníasson and cowriter Birgir Örn Steinarsson decide to give things a welcome spin by fast-forwarding to these girls’ unfortunate future.

They show a not-so innocent youth falling deeper under the darkened water of an addiction not yet formed. Magnea was an A-student who performed gymnastics with best friend Helga (Álfrún Laufeyjardóttir) before walking into Stella’s orbit. And she had a normal teenage relationship with her Mom (Sólveig Arnarsdóttir’s Jórunn), Dad (Þorsteinn Bachmann’s Hannes), and their respective spouses that cultivated an air of trust both sides knew was flimsy but also necessary. The first change is a desire to party hard, the second a craving for the artificial high her older friends could readily supply. Magnea’s initial hit of an intravenous substance arrives out of false necessity as her hold on reality becomes shaken. She pretends her tired parents with newborns neglect her and Stella’s attention fills the void.

There’s a definite connection between the two that might blossom into love. But just as we wonder if they’ll grow to be each other’s rock, Zophoníasson moves us a couple decades later to see Magnea (Kristín Þóra Haraldsdóttir) as a shadow of a human being yet to hit bottom (if she has one) and Stella (Lára Jóhanna Jónsdóttir) as the poster woman for getting clean, sober, and strong. He provides this glimpse to invest us in what comes next since those results are hardly expected. How does the girl with a support system see this unfortunate “phase” evolve into junkie living? How does the girl with nothing but an abusive boyfriend and cutthroat nature to get what she wants no matter the cost turn over a new leaf?

That’s what we stay to discover. Let Me Fall may show the steady decline of two teens before their mutual reckoning like so many others, but the knowledge of their respective endgames makes it infinitely more captivating. Rather than struggle with tragedy upon tragedy as we’re bludgeoned to death with sorrow and despair, we realize the story onscreen is more than simply a cautionary tale. There’s real heart involved here with the filmmakers depicting love in all its forms never being enough and sometimes being the problem. We know Magnea will do anything to be with Stella and witness how her parents’ can’t compete with that powerful hold. This isn’t a girl who drops off the map either. She’s always there reminding them of their failure.

What could they have done differently? It’s something we ask ourselves often as Zophoníasson deftly hides certain truths to let us wonder about things that will soon be exposed as out of their control. What if Magnea’s parents didn’t get divorced? What if there weren’t any younger siblings hijacking their time? What if? What if? What if? The question is as relevant as it is a crutch to move responsibility away from the person herself. We pretend that she wants to change — that she can change — while watching evidence to the contrary in real-time. And then we’re transported ahead to see a grown-up Helga run into this aforementioned almost unrecognizable Magnea and feel the knowing pain of so many years of regret like a punch to the gut.

We hear the older Stella speak of jail and buckle-in to learn more, unprepared for the treachery behind it. We meet the older Magnea’s Catholic conundrum of a boyfriend/pimp/abuser (Víkingur Kristjánsson’s Gísli) and see a photograph of their younger selves on a shelf to reveal just how much of this story has yet to be told. The only two constants are therefore Hannes and Jórunn’s heart-wrenching love that’s never enough to bring their daughter back from the brink and Magnea and Stella’s volatile passion that’s never enough to make them forget how much better the drugs are. Each performance within these truths (Bachmann and Arnarsdóttir alongside the double pairings of Halldórsdóttir and Jakobsdóttir with Haraldsdóttir and Jónsdóttir) is magnificently honest, their mutual helplessness as real as it gets.

It’s no surprise to learn Zophoníasson and Steinarsson crafted their script from true stories told by the families of addicts via interviews. There’s no Hollywood manipulation to give us heroes and villains, just the reality that we can all do better. One of their most memorable scenes doesn’t even include Magnea or Stella. Instead it’s Hannes, Jórunn, and their significant others in a heated discussion about what to do. The parent Magnea isn’t talking to wants to enforce tough love while the one who still has her ear asks if space might actually keep her close. They’re spinning their wheels without a clue as to a legitimate answer and it’s unbelievably refreshing. This struggle will only continue, culminating in an impossible conclusion like all the rest.

The best praise I can bestow is to say that I was constantly reminded of how addiction was portrayed on “The Wire” courtesy of Andre Royo’s amazingly three-dimensional character Bubbles. I was invested to the point that there were many times I thought Magnea and Stella turned a corner. Even though I knew where they ended up later (But who’s to say there won’t be another flash-forward to twenty years after that?), I thought happier days were finally here. In the end this only makes the lowest lows that much more unbearable and the promises spoken that much emptier. Soon events can’t help but become cyclical once the truth about who Magnea and Stella have always been is laid bare. Love ultimately destroys as powerfully as it creates.

Let Me Fall screened at the Toronto International Film Festival.