Introducing a screening of I Love You, Daddy at TIFF, director/writer/producer/star Louis C.K. was asked about his motivation for making the film, and stated simply that he has an affinity for “pissing on electric fences.” Provocation for its own sake unquestionably propels the movie. It takes tangible glee in making the audience uncomfortable, asking them pointed questions, and arising their ire, and does so without offering any answers or definitive opinions on the issues in question. This is fantastic if one wants to drum up internet chatter for a few days (C.K. is good at this, being a darling of the “Peak TV” era), but ruinous if one wants a work that can stand on its own long after the social media outrage/defenses/backlash/backlash-to-the-backlash cycle dies down.

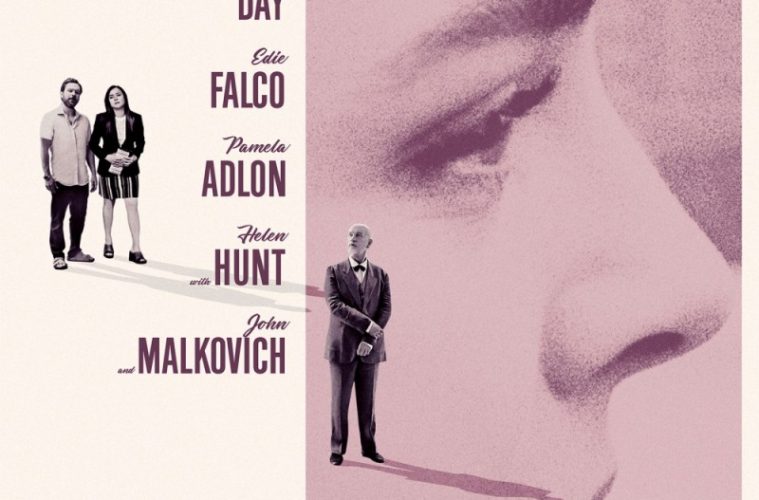

The strongest message or stance a viewer can glean from the film is that parents must be actively and consistently involved with their children’s lives, lest they find said children threatening to enter adulthood woefully unprepared. This is a tremendous “no duh” of an assertion, and while C.K. may get praise for delivering homilies about such obvious morality in his stand-up, it’s harder to pull off with a movie. In any case, the lack of such fortitude in lead character Glen Topher (C.K.) means that he abruptly finds that his teenage daughter China (Chloë Grace Moretz) is courting the affections of his artistic idol, movie director Leslie Goodwin (John Malkovich). A good deal of discussion amongst various characters ensues – the kind of extensive discussion which is fine in 20-minute blocks but limply stretches out at two hours.

Leslie is very, very obviously Woody Allen. Beyond the parallels in their respective reputations (when Leslie is first glimpsed, someone instantly blurts “Didn’t he molest that girl?”), the film is deliberately shot in black-and-white homage to Manhattan – which, remember, is about Allen’s self-insert character in a relationship with a 17-year-old. I Love You, Daddy is C.K.’s riff on the allegations against that director (and his onetime collaborator) specifically, as well as amorous liaisons between old men and young girls more generally. The parable is not subtle, to the point where the audience’s meta knowledge of the real events being referenced is likely part of C.K.’s extended troll of them.

In fact, the most interest that can be gleaned from the film is wondering about how much self-awareness is in play – so much so that a viewer might not just wonder how much it’s toying with them, but also how much it knows that we know that it knows, and even further complications of paratextual ponderings. For example, China is introduced slinking around Glen’s apartment in a bikini. The camera blithely ogles her, but the clear Lolita reference paired with the over-the-top thirst makes the wink to the viewer evident. But of course, even ironically leering at an underage girl is still leering. But the movie may be aware of that, too – and so could it then be said to also be commenting on ironic objectification? Maybe. Or maybe C.K. is just pissing on an electric fence, deliberately throwing out stuff he knows will get the clickbait flowing.

There’s no better example of this than an extended argument between Glen and his quasi-girlfriend Grace (Rose Byrne). There’s much discussion around the logic (or lack thereof) behind age of consent laws and the sexual agency of teenagers, all of which adds up to not much of anything. Of course real-life arguments rarely build to any coherent victory or agreement. But this is a film which otherwise pay stylistic lip service to Old Hollywood artifice, so this smacks of C.K. sneaking in some stand-up material he may feel he otherwise couldn’t get away with by putting arguments against age of consent laws in the mouth of a woman. It’s not as if a subject should be somehow off-limits to anyone to talk about, but any recipient of such talk is fully within both their own rights and senses to question why exactly someone may argue so vociferously about one particular subject.

And talk is all I Love You, Daddy offers. C.K. has proven to be one of TV’s best directors with Louie and Horace and Pete, but his adept camera work is absent here. Worse is the total absence of one of his greatest strengths: his willingness to use silence at length for both dramatic and comedic heft. Nothing here feels motivated; the movie uses a big orchestral score because the old movies did, it’s in black and white because Manhattan was, it was shot on 35mm because “it looks good” (C.K.’s words from the Q&A after the screening I attended). As a thinkpiece generator, it is absolutely spectacular – by every other metric, it’s a failure.

I Love You, Daddy premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival.