A lot can change in five to ten years and even more can unfortunately remain the same. When we first meet the Joyce family little Frances’ age has yet to hit double digits, her younger brother Patrick still clinging to their mom’s side. Their band of traveling Irish sing their folk songs and drink their stout, enjoying the freedom they live to protect — the same freedom outsiders love to destroy by lobbing racist and classist bigotry onto them as though they were savages. Michael Joyce (Dara Devaney) puts Frances on his shoulders to give the ol’ Muhammad Ali one-two while declaring her the greatest ever when a local Sergeant (Aidan O’Hare) arrives to cause trouble. The dust settles to show Michael leaving in chains, his wife tragically dead.

Writer/director Carmel Winters then fast-forwards the aforementioned span of time to show Frances (Hazel Doupe) has only grown stronger and fiercer with her fists since. It’s therefore hardly surprising to find out the boy she’s beating is the Sergeant’s son (Jamie Kierans’ Eamann). Just like that familial-based animosity has yet to dissipate, however, so too has the officer’s refusal to uphold the law when it comes these itinerant “tinkers.” He uses her father’s freedom as a means to strong-arm his way into an apology for no other reason than to feel a sense of unearned superiority. Frances and Patrick’s (Johnny Collins) grandmother (Hilda Fay) has made sure they’ve kept their noses clean, but the teen will always be her father’s little fighter — whether he likes it or not.

It’s Michael’s long-awaited release from prison where Float Like a Butterfly reveals the internal systemic patriarchy within this community that no one is keen on giving up. Besides Frances’ granddad (Lalor Roddy) egging her on to flex her biceps and keep the dream of meeting Ali alive, the rest are trying to push her towards domesticity. They joke that she needs a baby of her own to “calm her down” and turn her into a woman, but we wonder if that’s what her late mother would have wanted considering what we’ve seen of her childhood. We assume Michael will be on her side, but years away with the bottle have haunted him. He wonders if marriage is the only way Frances can be saved from her mother’s fate.

Winters places this girl in limbo as a result, her desire to be the woman her father always seemed to want against the woman society has decided she must become. The situation is only exacerbated by Michael’s desire to toughen Patrick up into what Frances already is — denigrating the identity she’s clung to for so long and abusing his son with emasculating rhetoric meant to transform him into something he’ll never embrace. Michael is perpetually drunk when he’s awake, a chip on his shoulder as far as the old ways of pilfering, yelling, and leaving whenever suits him. This is no longer that world, though. There are consequences to his actions and taking their trio on the road only provides more opportunity to learn how different it is.

He puts his kids into situations driven by selfishness. Yes buying a carriage to leave their old home is appealing to Frances because it potentially means growing closer and returning to how things were, but the alcohol and temper prove setting isn’t the issue. Michael is a broken shell of a man now and he’s yet to fully face his loss. This is why he pushes Frances and Patrick to fit into ready-made boxes he hopes will protect them from the trouble he’s wrought. Until he acknowledges what he still has, this family will never find their way. And if he’s not careful he’ll lose the children too — something he may unintentionally be trying to achieve. The world is against him and he doesn’t know how to cope.

Frances is therefore the lynchpin attempting to hold the peace with patience and compromise. She yearns for those rare moments when a glimmer returns to Michael’s eyes, the sense of adventure and immortality that drove him before. And when the drunk threatens to shroud everything back under pessimistic nihilism, she seeks to throw her weight around only to be met with vitriol. We can imagine Michael would have done anything his wife asked of him when she was alive, but his masculine ego struggles to project dominance now. So he’ll hit Frances and Patrick, putting them in their gendered places as though he didn’t just return to their lives days earlier. It comes off like the cowardice it is and frustration gradually builds within Frances in response.

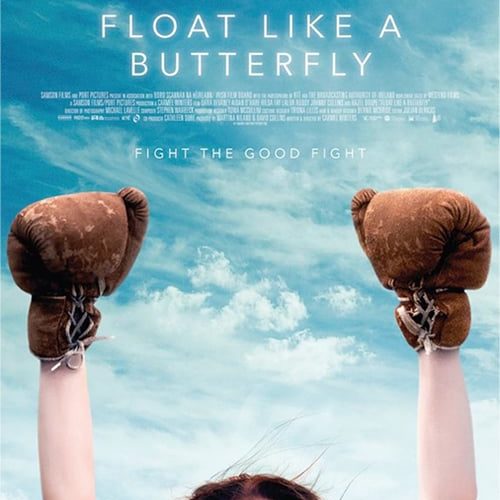

The film moves through their community’s customs to show their archaic conservatism and their need for revision. It pits Michael and Frances against one another until we see who truly has the other’s best interests at heart. Her fight proves internal against historical precedent rather than external in the ring — although we’ll eventually get that too. By then it’s rendered a symbolic representation of the struggle she’s already overcome. This is a girl clawing her way through the life she was given to grow into a woman for which her mother would be proud. Her last words to Frances were, “Never get knocked down.” Not by your enemies or the ones you love. To be the greatest is to fight for what matters and never, ever give up.

Float Like a Butterfly premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival.