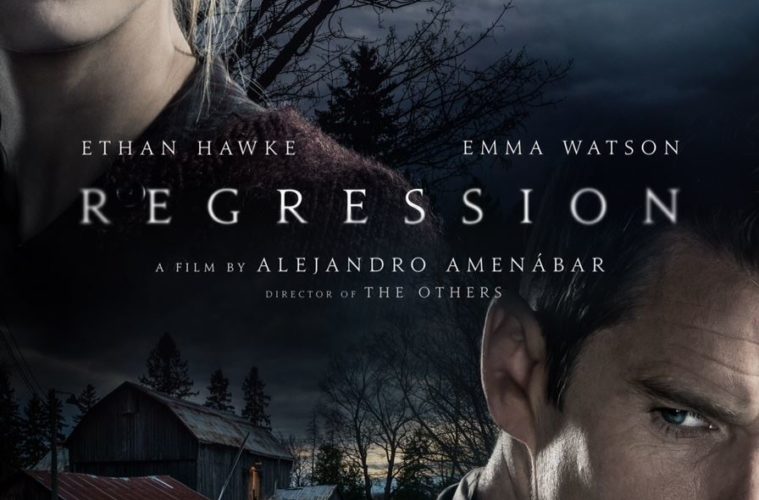

Absurdity turns quickly to boredom in Alejandro Amenábar’s Regression, the latest picture unceremoniously dumped by The Weinstein Company to your local multiplex with excess capacity. Set in a 1990 rural Minnesota, the story follows the adventures of Detective Bruce Kenner (Ethan Hawke) as he investigates a local “outbreak” of demonic possession that comes across his desk. Enlisting Professor David Rains (David Thewlis), they go on a wild adventure that eventually finds them briefly in Pittsburgh chasing a cult and a dark family secret that, at first glance, is less than what it might have been. Who would have thought a small town police department had those kinds of resources?

Amenábar gets the atmosphere right even if there’s not much lurking in the shadows, all while Hawke does his best to keep a straight face. At the heart of the film is a strong performance by Emma Watson as Angela, a teenager molested by her father John (David Dencik) – of course, the devil made him do it. Devon Bostick, no stranger to films about demonic possession (both as the sometimes evil brother at the heart of the Diary of a Wimpy Kid movies, and more chillingly as a teenager triggering haunting memories of terrorism and genocide online in Atom Egoyan’s Adoration), plays the son of John, banished to Pittsburgh for being a “sodomite.”

Perpetrating the cover story is town priest Reverend Murray (Lothaire Blueteau), that is until Bruce sees through what is a carefully constructed plot to cover up the abuse. The film along the way throws in a few jump scenes, scares, old ladies falling out of windows, and darkly lit confessions (both in church and in the police station) to add texture. Intended as a blockbuster chiller, the film tries to have it both ways, unsuccessfully combining horror/thriller notes with some very heavy material as John eventually confesses to his crime.

Giving the film the benefit of the doubt, the material is simply too thin to support a 106-minute-long version of this story without veering into boredom as the path to the confession is a tediously predictable one. The technical specs are competent, but the story never quite captures us because we remain ahead of it. The film’s central thesis, the MacGuffin that moves the plot forward, is even hammered home by its closing title card. I suspect storytelling like this — unless we’re diving much deeper beneath the surface — could only be sustained in short films. A 30-minute cut of Regression might have had me on the edge of my seat, but in its current form, it works better as a sleeping pill.

Regression is now in wide release.