If yours were one of only twelve Jewish families in all of Prague to survive World War II, you’d do your best to move forward despite the memories of death, fear, and oppression that marked you in a way no one who wasn’t there could ever understand. Some are better than others at pushing these aside to embrace the life that remained and future to come. Alfred Willer was one such survivor, a teenager at war’s end who eventually migrated to Brazil with his father Vilem for a fresh start. There he’d become a successful architect, marry, and have children: gifts that very nearly never were. And when those children took him to Europe to see his home, they couldn’t have been prepared for the horrors he’d share.

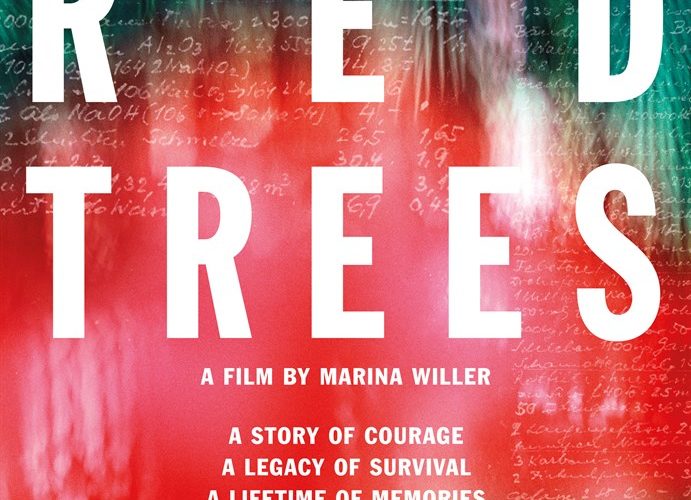

The stories were so vivid and important that his daughter Marina has crafted them (with the help of Brian Eley and Leena Telén) into her directorial debut Red Trees. Using his memoirs as a jumpstart (passages read in voiceover narration by Alfred and actor Tim Pigott-Smith), she’s decided to ignore convention by documenting his words through a lens of nostalgia rather than suffering. Willer doesn’t include archival footage of concentration camps or trains. There are no stock newsreels of bombings of even a single glimpse of Adolf Hitler if my memory serves. Instead we’re taken through the deserted buildings that remain, Alfred’s grandchildren running about, and the oft-photo portraying objects left behind. He tells us what he saw as a result of living rather than waiting to die.

It’s not surprising considering how young he was at the time. Because of his father (Vilem was a chemist who helped create the formula for citric acid), Alfred was afforded a larger sense of hope than most alongside a modicum of freedom to roam (they moved to Prague from Kaznějov, Czechoslovakia). He remembers the Jewish family that let them stay in their home—friends who’d inevitably die in the concentration camps while they remained. He talks of the large-scale bombing that hit Prague while he was out drawing the city’s mixture of architectural styles, the massacre at Lidice mere kilometers from home, and the mass deportation of everyone he knew, including his grandmother. His words fill the empty rooms Marina visits, speaking secrets that must never be forgotten.

She ultimately depicts her father as everything the Nazis weren’t. Born in a place and time with baseless rules, segregation, and finally genocide, he would settle in a land of pure acceptance. Willer takes pains to show Brazil’s melting pot—no matter how briefly—of race, religion, and language. Alfred was one of many bilingual Europeans choosing not to speak German post-war, the Czech learning a third language instead (Portuguese) to excel in his new land. He would raise his family in a world of equality and love, the ripples of what he endured isolated in the hopes his children would never have to go through anything of the sort themselves. And now in a new era of refugee crises, he and Brazil are role models for compassion.

Marina juxtaposes his memoirs with impressionistic visuals moving beyond literal representation into an abstract and emotionally charged context. She uses film from the present over words from the past; close-up footage of rain on windows, trees blowing in the wind, and puddles with blurred reflections capturing movement. What’s onscreen proves to be poetry—images full of promise, history, and love transitioning back and forth as we listen to the harrowing tales of a young boy up against the clock of war and see what he’s become as an older man engaged in his grandkids’ lives. It’s tragic to think of all the people lost and the good they never accomplished. Alfred didn’t take his survival for granted. He made good on the promise to give rather than take.

The title is a play on Alfred being color-blind—an ailment discovered early when drawing trees with a red pencil. He talks about the Nazis burning their land and how he saw “red trees engulfed in flames.” Marina uses his literal color-blindness as a way to also say her father sees the world through a lens of equality (his grandchildren ask whether the world would be better off with the same handicap turned blessing as a way to erase racism and prejudice altogether). It’s an admirable if forced theme that a montage of Brazil’s diversity does a much better job explaining later on. But those words “red trees” also conjure aesthetic feelings in this idea of beauty through destruction. Of surviving despite horrors and refusing to be broken.

Willer’s essay film is obviously a cathartic experience, her documenting a family history that transcends the personal towards the universal. She puts herself and relatives in to show the product of her father and grandfather’s strength—proof they’ve instilled a sense of pride and work ethic through the knowledge that nothing is guaranteed. The way Alfred recollects the nightmarish things he witnessed is so matter-of-fact because it must. He recounts facts and terror with a detached air, educating us both about the events and the ways one lives despite enduring them. Marina shoots the deserted factories and camps as the untouched installations of paused history they are. Stories told in present remain stuck in the past, each a somber lesson to take to heart and know life prevailed.

Red Trees is now in limited release.