It begins with the abduction of a girl. The scene is quiet and innocuous until it isn’t—a car rolling up to a young girl to ask for directions as children play in the background. The driver says, “Are you Anna?” before a man grabs her and shoves her in the car the instant she says, “Yes.” We watch as though a voyeur behind the trees, helpless to do anything but wait to see what happens while a boy on his bike (Dante Hoagland‘s Howie) rides into frame for the camera to follow home. These suburbs are small so his destination just happens to be next door to the house we’re about to spend the night within. That family’s new babysitter is also named Anna and suddenly we realize what’s gone wrong.

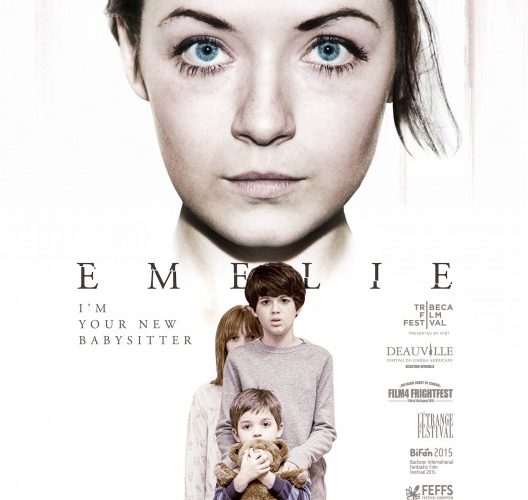

Richard Raymond Harry Herbeck‘s disturbing script and director Michael Thelin‘s willingness to render the dark corners of those pages are quick to position us for what’s to come. Tiny details like “Anna’s” (Sarah Bolger‘s titular Emelie) fear when Mr. Thompson (Chris Beetum) mentions her babysitting Facebook page put us on our toes while the easy lies throwing him off the scent of her ignorance towards the names of other children she watches that he knows are chased with a smile. The Thompsons (rounded out by Susan Pourfar) were in a bind and desperate for a night to celebrate their thirteenth wedding anniversary. When usual sitter Maggie (Elizabeth Jayne) canceled, the recommendation of her friend Anna worked. And without proper time or just cause to confirm her identity, they lead Emelie into their home.

She wastes no time systematically gaining the kids’ trust as soon as the parents leave by enticing them with exactly what she knows they want. She provides nine-year old Sally (Carly Adams) another female to counteract her two brothers. Four-year old Christopher (Thomas Bair) gets the laissez faire demeanor necessary to let his hyperactivity run amok in pure joyous fun. And it only takes a few thinly veiled hints of flirtation to coax eleven-year old Jacob (Joshua Rush) out of his room to join the wild party of property destruction, wall painting, and cookie gorging that follows. It all leads to a simple game of hide-and-seek that Emelie’s overt sexuality helps Jacob agree to play. While he counts to one hundred and the others hide, she strolls around looking for ammunition.

The film is definitely not for the faint of heart or cautious parents already too paranoid to let their kids grow up with the same childhood they probably had. Because while drawing on the walls or eating sweets are frowned upon and grounds to get the babysitter in charge fired, what Emelie does next should make parents’ skin crawl. I’m talking the discovery of Mr. Thompson’s gun left on the bed for the children to find, the recruitment of a Middle Schooler to help in the application of a tampon, and the introduction of a sex tape for “movie time” that brings all sense of decency to a new low—and a couple older audience members’ tolerance level to ground zero as effective horror thrillers should.

At the back of everything are two important components: one worth mentioning and one to discover on your own through the course of Emelie’s devolving state of innocence and responsibility. The latter entails the why of hers and her accomplice’s (Robert Bozek‘s “Skinny Man”) actions, the former foreshadowing Jacob’s position as man-of-the-house and his need to finally exit from behind teenage angst and electronic games to embrace it. What Emelie doesn’t anticipate when she clouds his mind with false attraction is that his siblings’ wellbeing possesses the power to break her spell. At some point the freedom allowing them to—as Sally says—”break the rules” their parents have instilled go too far. Then it’s a matter of what Jacob is capable of doing to save the day.

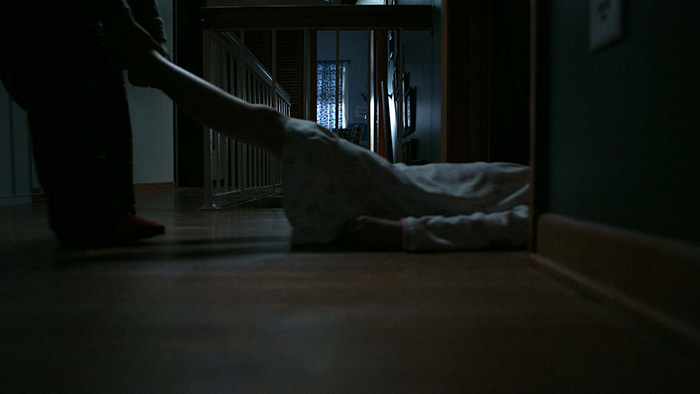

This results in a race against time. The “Skinny Man” watches the Thompsons at dinner to warn Emelie when they are about to leave and Jacob seeks new ways to find assistance in a house without cellphones (thanks to a family rule) and internet (thanks to the babysitter’s meticulous track covering). This brings Howie unwittingly into the fold and Maggie to arrive in confusion to the fact her friend Anna hasn’t been returning her texts. Each of these outside interferences starts pushing Emelie to the edge of restraint until blood is spilled and the timetable to do what she’s come to do accelerated. And the horrors aren’t simply courtesy of her pitting the kids against one another either. Some things are out of her hands like little Christopher finding that gun.

Filmed in and around Clarence, New York—a suburb of screenwriter Herbeck’s hometown Buffalo—Emelie isn’t shot like a low-budget indie in a small town by its own residents. There’s true visual intrigue in the shot selection from street views of the “Skinny Man” into the restaurant the Thompsons eat at to the carefully obstructed set-ups inside the home that keep reactions paramount to their cause. I loved the “movie time” scene because we’re behind the television watching Sally’s horror, Christopher’s naiveté, and Emelie’s relish while sex noises emanate to explain very succinctly what’s happening out of view. The violence is in turn rendered with a minimalistic flair to welcomingly keep things more psychological mood piece than torture porn.

That’s not to say there isn’t a fair share of blood when all is said and done, though. Thelin is hardly shy with moments of surprise brutality in the safety of an automobile ride or one’s own home. He and Herbeck throw the Thompson children into the fire and watch them burn before providing a slim chance for escape if Jacob proves up to the challenge. And through it all there are few if any instances that don’t feel authentic—either abject fear (Sally gets the shaft throughout) or glowing pride (Christopher surprising Emelie by going above and beyond his age’s ingenuity). Its best moments come from Bolger and Rush’s dynamic. What begins with inappropriate thoughts moves to a battle of wills and smarts. Only one can win.

Emelie is now in limited release and available on VOD.