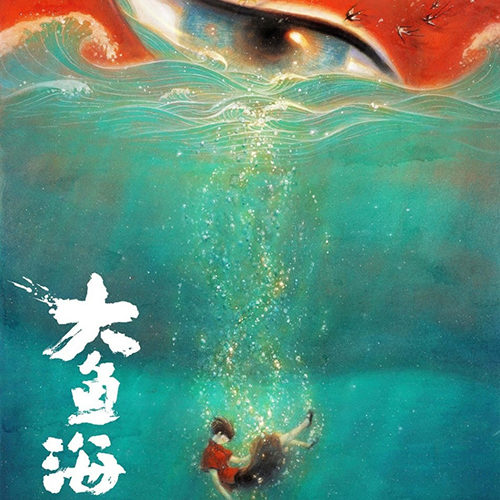

In 2004, directors Xuan Liang and Chun Zhang created a Flash animation for an online contest. From there they expanded it into a feature length film steeped in Chinese supernatural legend. And despite some funding snags over its twelve-year production schedule, Big Fish & Begonia turned its approximately five million-dollar budget (in today’s US dollars) into just shy of one hundred million at the Chinese box office. Now it makes its way to America two years later for a limited release, another stellar example of the nation’s growing animation industry. With its beautiful aesthetic and distinctive tale of life, death, and love, the film should find a welcome audience.

The story takes place in a magical world that exists beneath the human world in an alternate, spiritual reality. Its inhabitants are mostly humanoid in appearance, their supernatural powers attuned to the natural forces of the world. Known as “Others,” these God-like beings embark on a seven-day journey on the human plane on their sixteenth birthday, marking their evolution from adolescence to adulthood. This weeklong exercise sees them transforming into red dolphins that swim through a portal from sky to what human beings know as the ocean. After the seven days, the “Others” are given the choice to stay in the human world or return to their own.

This decision is almost taken out of young Chun’s (Guanlin Ji) hands when her curious dolphin form stumbles upon and gets entangled in a fisherman’s net. Luckily, Kun, a teenage boy (Timmy Xu’s) and his little sister, Jiu’er, see what happened. Kun jumps into the water to free her, getting caught in the same net that traps Chun and drowning in the process. Kun gives his life to save Chun — something she doesn’t forget when she takes his ocarina back to her plane. While searching for a way to resurrect him she hears a voice proclaiming the ability to help. Soon she’s sailing the clouds toward the home of the Soul Keeper, a creature who’s always willing to make deals.

From there we watch Chun keep her secret. Kun’s soul is acquired as a tiny dolphin inextricably connected to her own. It will grow larger until the time is ready to ride that magical column of water into the sky and therefore back to his world, but it will do so under the threat of danger as its creation has altered the delicate balance built. Omens occur portending disaster with heavy rains; another being like the Soul Keeper — his opposite in a bucktoothed witch watching over the souls of sinners who’ve taken the form of rats — arrives with an obviously duplicitous nature; and those in Chun’s town divide into one faction willing to help her repay her debt to Kun and another seeking to destroy him.

The result is a fairy tale weighing the cost of sacrifice against itself. It asks us to look past the selfless desire to save someone at the ramifications of what doing so may create. What does Kun’s death leave behind? Is the resulting pain worth Chun’s salvation? What does her protecting his impossible existence risk despite it being sanctioned by her people’s devious and opportunistic divinity? Is letting him reunite with his distraught sister more important than the sorrow of another sister left alone in the aftermath of uncertain tragic circumstances to come? And where does this cycle of gifting life end? Can it? If Kun can save Chun and Chun can save Kun, when does life’s value diminish to zero? Without death, life proves meaningless.

And it’s not just atonement in the sense of paying someone back. There’s also the sacrifice we’re willing to make for love. When Chun and Kun meet as dolphin and boy respectively, there isn’t the sense of togetherness they find once their forms are reversed. They save each other as an impulse and moral imperative. This is why Liang and Zhang’s story also includes love whether it’s from family (Chun’s grandparents) or friends (Shangqing Su’s Qiu). These characters take stock in what Chun means to them and what her well-being means in contrast to anyone else’s — including their own. They know what she’s done is wrong in a bigger picture sense. They know their entire world could be destroyed as a result and yet they help her anyway.

The result is a fantasy adventure with high stakes despite death seeming impermanent throughout. Rather than be about finding eternal life like many tales of its kind are, Big Fish & Begonia is about giving it. So it’s only a matter of time before the sky opens up with apocalyptic force, the erasure of mortality tearing a hole into the fabric of existence because it must. There will come a moment when no one can blindly ignore the cost of their decisions. Chun and the others will face a choice pitting one against many. They will watch others steal their chance at altering fate and even more refusing to let anyone cheat their destiny to the point of giving their own lives to ensure the loop is closed.

Mortality meets immortality. Reincarnation meets eternal imprisonment. And no one concept is better than the next. Liang and Zhang prove they’re all equal and quite possibly interchangeable if we’re willing to embrace them with full hearts. What is life without someone to share it? It can be a lover, family member, friend, or pet. It can be a memory that lives on forever in the form of some inanimate object imbued with the power of someone no longer here. These totems become our keys between worlds even if they only exist in our heads because a feeling can be just as poignant as the real thing. Value is a construct. One life or many isn’t a choice because losing one is as unforgivable as losing all.

I think it’s important for kids to experience this type of eastern culture as a means to break free of the often-debilitating rigidity of monotheism. This film delivers it in the form of cutely inventive characters (that had me thinking about Spirited Away) that must reconcile what they know against what is possible. It’s a dream world of magic — of fire and flowers sprouting out of thin air as dolphins sleep in death and swim in life. There are nefarious creatures with ulterior motives that use kindness for personal gain and others that use deception for secretive communal betterment. Sometimes we must risk everything because it’s the only way to show others they can too. And who knows? Maybe your sacrifice is noble enough to earn a second chance.

Big Fish & Begonia opens in limited release on Friday, April 6.