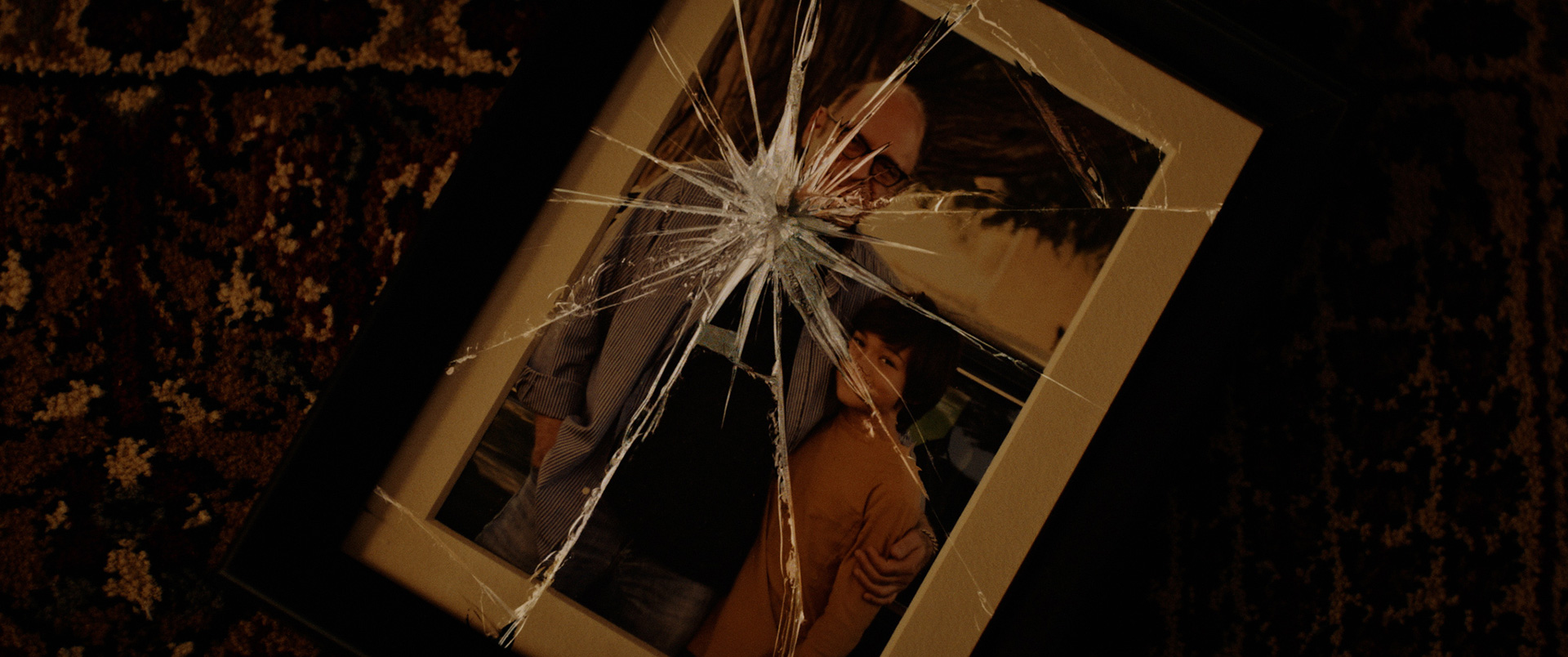

There’s a reason young, mute Dylan Jacobs (Ezra Dewey) longs for a voice and it’s not simply an ableist fantasy striving for some misguided ideal of “normalcy.” A bit of that is present (he’s a child seeking friendship and community, after all), but the reality is that he sees his silence as the reason why his mother (Tevy Poe) left. He’s starting over in a new apartment with his radio DJ father (Rob Brownstein’s Michael) and yet he still can’t forget the night he awoke to find her crying in their kitchen. His dreams are haunted by her depression and his waking hours are spent wondering about his contribution to its formation. The discovery of an occult book promising him a wish is therefore too intriguing to ignore.

In familiar “Monkey’s Paw” fashion, however, writers/directors David Charbonier and Justin Powell aren’t seeking to grant it without a price. So rather than a genie, they’ve conjured The Djinn. With some blood and a candle, Dylan is given the tools to awaken this dark force and set in motion the gauntlet necessary to win his wish. Survive one claustrophobic hour in his two-bedroom apartment with this spirit as it takes human form through the bodies of the dead, blow out the flame once midnight strikes, and pray that which you will end up losing doesn’t outweigh that which you gain since it’s usually what we lack that makes us who we are. Wanting more can often blind us from acknowledging our true strengths before ultimately consuming them whole.

It’s a cool concept with the potential to enthrall and scare in equal measure despite an indie budget necessitating a single locale to offset the costs of effective special effects. Where things go awry, however, is the fact that we’re dealing with a child in an unfamiliar place with little at his disposal to truly have us believing that he stands a chance. And with an almost real-time trajectory following Dylan’s desperate attempts to elude this predator that he invited, watching him constantly luck out and live to evade another minute can get old very fast. Because what can he really do besides slow this creature down? How can Dylan survive the night unless his pursuer decides to always disappear right when it seems all hope is lost?

The answer is simple: he can’t. For every battle this boy wins, there are three that conveniently end early. I’m all for suspension of disbelief, but the entire film can’t hinge on that concept alone. Charbonier and Powell at times seem to make it work because they seem to make it look as though nothing is real—that Dylan is working through his own guilt and self-pity and thus can’t be in actual danger because his mind won’t allow him to be injured—but that’s not the case. This scenario is happening. The dark magic that has brought the Djinn to life has given the candle flame permanence and the stakes physical heft to go along with the psychological scars. This monster packs a punch … when allowed.

How often that proves the case leaves a lot to be desired, though. The past saves the day in certain cases since Dylan’s memory of that night with his mother comes into clearer focus as the movie progresses so we can glean more details about what “leaving” means, but the constant jolt sending us back to the present to watch another narrow escape exacerbated by implausible cuts creating more safe distance than the attack provided the previous frame erases any gains as soon as they are earned. The atmospheric lighting coupled with Matthew James’ synth score (the setting is 1989) can only do so much to create suspense after we realize nothing can actually happen. Dylan must stay alive for those sixty minutes. It’s pointless if he doesn’t.

Why? Because the wish can’t be granted until then. Charbonier and Powell have written themselves into a corner that guarantees the diminishing returns of repetitive sequences devoid of individual payoff. Will Dylan escape the bathroom? Will he escape the closet? How about hiding under the bed? He has to because he’s yet to blow out the candle and get us to the only place the plot has to go. And the circuitous nature of this cat and mouse chase might have been worth it if the conclusion wasn’t so predictable in its conventional genre trappings. It makes sense and it may be the only way you could feasibly end this nightmare, but we’ve practically spent eighty dialogue-free minutes with little to do but anticipate exactly what comes next.

It’s too bad because the production value is fantastic. Early scenes of the Djinn in its true form are memorable in large part because everything is kept to the corner of our eyes. Once things demand that the Djinn have physical form, however, things devolve into random humans trying to kill Dylan while he stays out of arm’s reach. I longed for that smoky haze and red glow, though, excited with each return only to find another clunky set piece doing somersaults to ensure our hero barely avoids death. I wonder if the budget was perhaps too small to overcome since every moment The Djinn appears ready to transcend, it tragically deflates. Or perhaps its conceit deserved short film status instead. Going beyond twenty minutes simply isn’t viable.

The Djinn hits limited theaters, VOD & Digital HD on May 14.