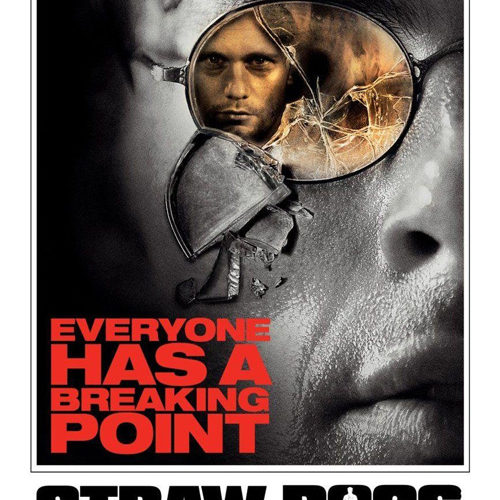

Rod Lurie‘s Straw Dogs is a tough film to watch. Not in terms of onscreen violence, but in evaluating the film as a whole. Sam Peckinpah‘s original film is renowned for its controversy, but by no means a universally beloved classic. It’s a cult film, but a skillful one about nihilism and unleashing the inner-animal that Peckinpah believed all men caged.

This remake’s intentions are not about that. Lurie does delve into the original’s theme of what being a man means, but he’s clearly not going for the full on lead villain take Peckinpah went with. David and Amy start off as genuinely good people. David is still condescending, but not in malicious way.

The original was about David becoming a villain, a dweeb who begins to revel in violence and terror he’s causing. The math mathematician believed he was becoming a man, but instead he became a monster. Here, David becomes a more tamer beast, but the film and its characters seem to think he’s a man.

As my audience erupted into cheering on David, usually with shouting “Get him!” or “Kill ’em!”, I felt uncomfortable during David’s violent stand. That unnerved feeling wasn’t due to the standard onscreen violence, but because of David’s portrayed heroism. The screenwriter finds an animal in himself, and he seems to embrace it for a moment. The film acknowledges his transformation as “finding a man in himself,” which is a sentiment expressed by Charlie, but he comes off as enjoying this newly found machismo.

When the camera gives a slightly low-angle hero shot of David cleaning his glasses and playing music, it’s going for heroism. David straddles the fine line of doing what’s right versus becoming almost as worse than the men he’s fending off, and he doesn’t always fall on the former side. When David tells one of the Charlie’s lackies that he hopes he slits his throat while his neck is placed above broken glass, it’s a sign that this is no longer a humanistic and rational man. He becomes someone willing to go to extremes he perhaps doesn’t have to go to, to prove his supposed “manliness.” It’s far less cynical and dark take than the original’s, but still, there’s hints of nihilism.

If there’s one deviation made from the original, it’s the change in subtlety. Peckinpah was restrained with his conflicts and thematics, while Lurie gets a tad too heavy-handed at times. Certain scenes go too far to prove a point, mainly due to an overaly apparent score and letting certain scenes play out longer than they should. A prime example is the flashback sequence, which was used more unsettling in the original, during a high school football game. During the local home opener, Amy can’t stop thinking about what was done to her. Lurie could have let Bosworth’s — who’s never been this good — face say everything, but her clear internal pain is intercut with needless flashbacks. There’s no reason to show what’s eating away at her; we know.

When Lurie lets certain ideas lie beneath the surface, that’s when his remake operates best. With more dramatic restraint and well-rounded supporting players — like Walter Goggins‘ as Jeremy Niles’ barely present brother — Straw Dogs could have been more than a well done modernized thriller. But by the brutal end, the film ends up working on its own terms.