Exceptions almost certainly must exist, but it remains a challenge to name any single visual “flair” with more limited and less effective purpose than an elongated first-person shot. Best reserved for the interactive nature of video games or the short-span gaudiness inherent to particular forms of advertising, its utilization in film has thus been a troubling matter; when Brian De Palma could fully ape such a process in the span of merely four minutes some 32 years ago, any sign of a new (or, at the least, “original-seeming”) direction is necessary for its survival. Better, then, to manipulate its possibilities from top to bottom while still maintaining a veneer of simplicity.

Sticking to this form of application is among the largest compliments that can be paid to Maniac, director Franck Khalfoun’s 21st-century update on the ‘80s horror sleaze fest (an unlikely source of inspiration for Michael Sembello‘s radio hit) which does not hesitate to stock griminess and visual discomfort to its own ends by way of a rarely broken, direct dive into the killer’s point-of-view. It’s a visual strategy and thematic gesture that rarely strikes more than one note — i.e. we’re being put in his shoes! — but for consistently instilling discomfort does Maniac, regardless, still hit said note with resonance.

But it attains a more cogent purpose when the gore and misery accumulates (where most horror titles slip) to such an extent that, at their greatest points of exuberance, Khalfoun’s images — by their very design — begin to explore a precarious line between viewer observation and strange, inured levels of complicity in the action. The recognition is alternately stimulating and problematic: a few kills (as well as their grisly aftermaths) land as too much of the setpiece and money shot variety (i.e. the kind that will eventually appear in some YouTube compilation or, whatever else falls into that morally questionable ilk); it’s to their credit that much of the remainder is far too upsetting, and intentionally so, to feel in full dialogue with those of the “entertaining” variety. If such schemes are not fully workable, Maniac nevertheless remains the most visually competent example of long-form, first-person cinematic storytelling this writer can think of. (Sorry, Gaspar.)

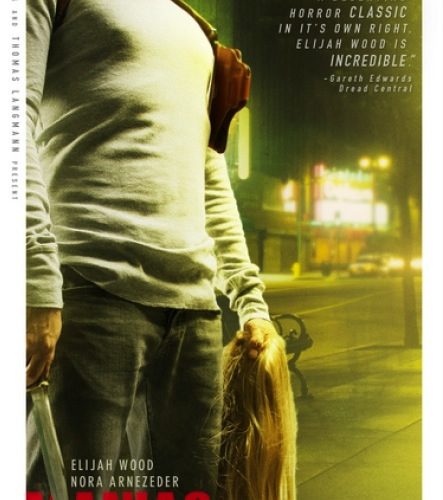

It should go without saying that distinct paths for ever-dominant aspects will color that which surrounds; as far as performances go, the final outcome is notably scattered. The unlikely center of Maniac’s nasty business is Elijah Wood, whose now-common, even typecast image as a heroic, soft-voiced type — by all means a potential impediment — is by-and-large masked in the picture’s perspective. (The system devised by Khalfoun which brings him into a line of sight is, often, precisely what you’d expect: the guy has a thing for staring into reflective surfaces. Your expectations as to its effectiveness and reliability are, too, likely on-point.) Understandably so, an overwhelming quantity of dialogue is delivered in a not-quite-voiceover manner (this once more brings the video game medium back to mind), and it’s as a result that Wood feels a bit trapped at nearly every turn. No matter his capabilities as a performer — something which, to this writer’s mind, have been well proven by now — the tortured line readings of a diseased mind (as penned by Alexandre Aja, Grégory Levasseur, and C.A. Rosenberg) always strain for some credibility while never entirely reaching their endpoint.

Because Wood is the only significant male presence Maniac has to its name, the female performances come to establish a more significant dynamic than the typical flee-in-terror horror staple. Much of the expected work is put in — loud screaming, running in high heels, foolish promiscuity — though the first-person emphasis on frightened, contorted faces manages to do them favors which Wood is not so lucky to have been afforded. This is potentially seen as an unfair advantage, but, like much of the film as a whole, any surrounding faults feel harder to pick at when they clearly stem from a place of refreshing, gratifying-enough ambition.

Perceived effects notwithstanding, the modes of operation behind Maniac begin to buckle under themselves when some misguided psychological reach ends up exceeding a grasp on smarter-than-average horror fun. What a shame that trying to build character serves as its fatal flaw: despite a neat play with perspective — something for which Khalfoun and the screenwriters should be commended; it’s among their best manipulations of the format — flashbacks explaining the serial killer’s origin are hugely rote (would you be surprised to learn his mother was a drug-addicted prostitute?), while romantic binds ring similarly hollow. French lead Nora Arnezeder is handed a fascinating dynamic — “fascinating” must be apt when the performance requires her to form a love connection with the cameraman throughout — yet she, too, is trapped when Maniac‘s screenplay can’t be bothered to zero in on a human emotion which goes past the immediate and gruesome.

In this sense, it’s perhaps best to consider the end result both a fine direction for Khalfoun as a visual stylist, and, more importantly, a new way of considering first-person dynamics in cinema. Excepting that this venture is an admittedly mixed bag, its intentions always feels coherent, to the point of strange cohesiveness in all the ways things do and do not manage to click together. For an ‘80s remake packing the right amount of gore required to satisfy horror-consuming masses, that’s a fine feat of its own.

Maniac opens in theaters and arrives on VOD Friday, June 21st.