While it’s not a topic that’s foreign to the silver screen (see any John Hughes movie or Larry Clark’s Bully or Jacob Aaron Estes’ Mean Creek), bullying is a subject that has been generally glossed over, never examined that thoroughly.

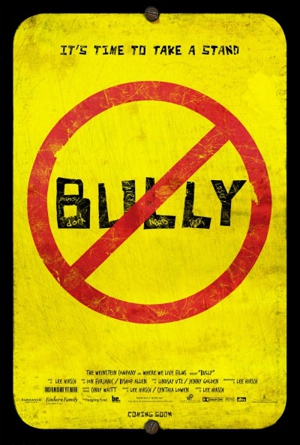

Cue Lee Hirsch‘s documentary Bully, a simple, precise and affecting film concerning the effects of The Bully, that infamous villain that we’ve all played or encountered, be it in big ways or small, at some point in our adolescence. The subjects examined in Hirsch’s film are the most extreme victims of this trend; young kids, ranging from 11 to 17-years old, and the physical and psychological turmoil mostly nameless bullies put them through day in and day out.

Alex, the relative anchor of the film, is a young 12-year old in a Sioux City, Iowa middle school who faces constant ridicule from a group of both middle school and high school students on the bus every day. He’s got a wider nose than usual, so they call him “fish face.” He’s a little different, so they call him “faggot.”

In Oklahoma, a 17-year old girl named Kelby explains to Hirsch and his team what happened when she came out to her parents. “Once she came out, everything changed overnight,” Kelby’s father explains. “People we knew for years stopped waving to us when they passed.” Kelby admits to trying to commit suicide three separate times. Despite this, she refuses to leave town, convinced this will mean the bullies won. These bullies include her teachers, who tell her that faggots burn.

We are introduced to the Long family, still trying to survive their 17-year old son Tyler’s suicide. They fight their school board on a daily basis, determined that someone in the system take responsibility for the actions of those who abused their son, pushing him to take his own life. The school board does nothing, barely attending the town meetings the Long family lobby for.

Each subject – there are 5 bullied victims presented here – are documented rather traditionally by Hirsch. He interviews the parents, the school administrators, the friends and the victims themselves, those of them who haven’t already taken their lives. While Hirsch doesn’t flinch from the proceedings, determined to show bullying at its absolute cruelest, he never spends quite enough time with any one subject. We get a taste of the pain each of these family’s face, but are never thrust into their world the way each set-up promises. Add to that segments of extended b-roll accompanied by a slightly over-the-top score by Michael Furjanic and indie band Bishop Allen, and all the strides Hirsch takes to build mise-en-scene realism are briefly forgotten. On the other side, sometimes Hirsch (also credited as cinematographer here) spends too much time focusing then purposely not focusing the camera, a recent stylistic troupe in the indie world that has fast grown tiresome.

The emotions on screen, however, are easily transferable. We feel anger when Alex’s parents confront an assistant principal of his school about the escalating bullying – a recent incident involved Alex getting stabbed with a pencil on the bus. We watch this administrator shrug off these parents with laconic plight and faux-sentimentalism. Then we watch Alex’s parents try to rationalize to themselves that Alex hasn’t been truthful to them about the stakes of the bullying, when we, the viewers, know that’s not true. So are anger shifts to these parents.

Hirsch, it must be said, has a very clear agenda in place. He’s out to expose bullying, rather than study the motivations behind the actions. And so he glosses over perhaps the two most complicated victims, young Ja’Maya and Ty Smalley. Ja’Maya, after being bullied day in and day out on the bus, finally brings her mother’s gun on to the bus and shoves it in her bullies’ faces, all caught on the bus security camera. She’s sent to a psych ward with nearly 50 felonies pending. Only briefly do we see a member of the justice department explaining his counter opinion: that no amount of bullying justifies bringing a gun on a school bus. This is not a ridiculous thought, so Hirsch steps away from it.

Similarly, the tragic story of Ty Smalley – the young, bullied 11-year old who took his own life. We are introduced to this tale late in the film and only briefly introduced to father Kirk Smalley, who’s used the death of his son as a worldwide platform to end peer-to-peer bullying. While it’s a poignant note to end on, the entire subject is glossed over a bit too hastily.

Despite these complaints, the proof, as they say, is in the pudding. These are brutally real stories told by real people, and no amount of shaky, unfocused frames or melodramatic melodies can take away from their words.

Bully is now in limited release.