We have a lot to cover in this, our last roundup of new and recent books on film and pop culture before year’s end—high-profile memoirs, the coolest collection of crossword puzzles in history, a dash of Mac & Me. So, let’s get right to it. Happy holidays, and happy reading!

Cinema Speculation by Quentin Tarantino (Harper)

Quentin Tarantino wrote one of 2021’s most notable film-related books, a tremendous novelization of his own Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. He follows that success with what just might be 2022’s best film-related books, Cinema Speculation. It is a collection of essays built around films seen during his adolescence that impacted him greatly. Some, like Deliverance and Taxi Driver, are canon. Others, like 1973 crime drama The Outfit, are not. The experience of reading Speculation is akin to hearing Tarantino zip through his childhood movie habits—the text mostly focuses on films between 1968 (Bullitt) and 1981 (The Funhouse), although references are made to works from all eras of cinema. There are a great many oh-so-Tarantino elements in the writing, of course—the snarky put-downs of the likes of Truffaut, de Palma, and Altman; personal what-ifs (Paul Newman or Gene Hackman as genial bail bondsman Max Cherry?!); some pleasurable name-dropping (tidbits are relayed from conversations with folks like Walter Hill, Peter Bogdanovich, and even Steve McQueen’s first wife, Neile Adams); alternate readings of Invasion of the Body Snatchers and The Getaway; adoration for character actors like Joe Don Baker and Dirty Harry’s Andy Robinson; disappointment with the endings of Heat and Sisters. However, what I found most beguiling about Cinema Speculation is its level of emotion. Some of these examples are memories from his own life, including a life-altering experience seeing Jim Brown in Black Gunn with his mother’s boyfriend. Most affecting is Tarantino’s tribute to doomed Daisy Miller star Barry Brown. He played the title character’s suitor, Frederick Winterbourn, the much-derided Bogdanovich vehicle. Brown is a figure who, in an alternate universe, may have ended up as a QT reclamation project. That was not to be Brown’s fate, sadly: “[T]he year of that film’s release, at the age of twenty-seven, Barry Brown took his own life. Turning all of us who liked Barry Brown, when we watch the end of Daisy Miller, into Winterbourne. Who was Barry Brown? What did it all mean? Am I the only one who remembers Barry Brown? Am I enough?” Cinema Speculation is a sign that if Tarantino does eventually go through with his oft-mentioned early retirement from directing, his second career—author, not actor—will keep his fans thrilled.

Citizen Spielberg by Lester D. Friedman (University of Illinois Press)

After seeing (and adoring) The Fabelmans (review here) at the Toronto International Film Festival in September, I was thrilled to dig into the second edition of Lester D. Friedman’s essential study of Steven Spielberg’s life and career. It is especially noteworthy due to the inclusion of Spielberg’s genre-hopping efforts since the book’s first edition: Munich, Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, The Adventures of Tintin, War Horse, Lincoln, Bridge of Spies, The BFG, The Post, and Ready Player One. (West Side Story is referenced but the book was written prior to the release of the 2021 musical.) In addition to the inclusion of this beguiling collection of films, Friedman takes close looks at some of the more ignored works in Spielberg’s filmography. In particular, I’m thinking of the author’s analysis of 1989’s Always, one of the few entries of the director’s career I’ve never felt was necessary to own: “Why is Always the most forgotten film of Spielberg’s career?” Friedman asks. “I think audiences did not anticipate Spielberg’s ambivalent and clearly melancholy attitude toward love, his growing understanding (perhaps as a result of his recent divorce from Amy Irving) that it can be detrimental as well as nourishing, dangerous as well as uplifting.” Perhaps Friedman’s greatest achievement is deciphering—in remarkably entertaining fashion—why every Spielberg film is vital to understanding his entire career.

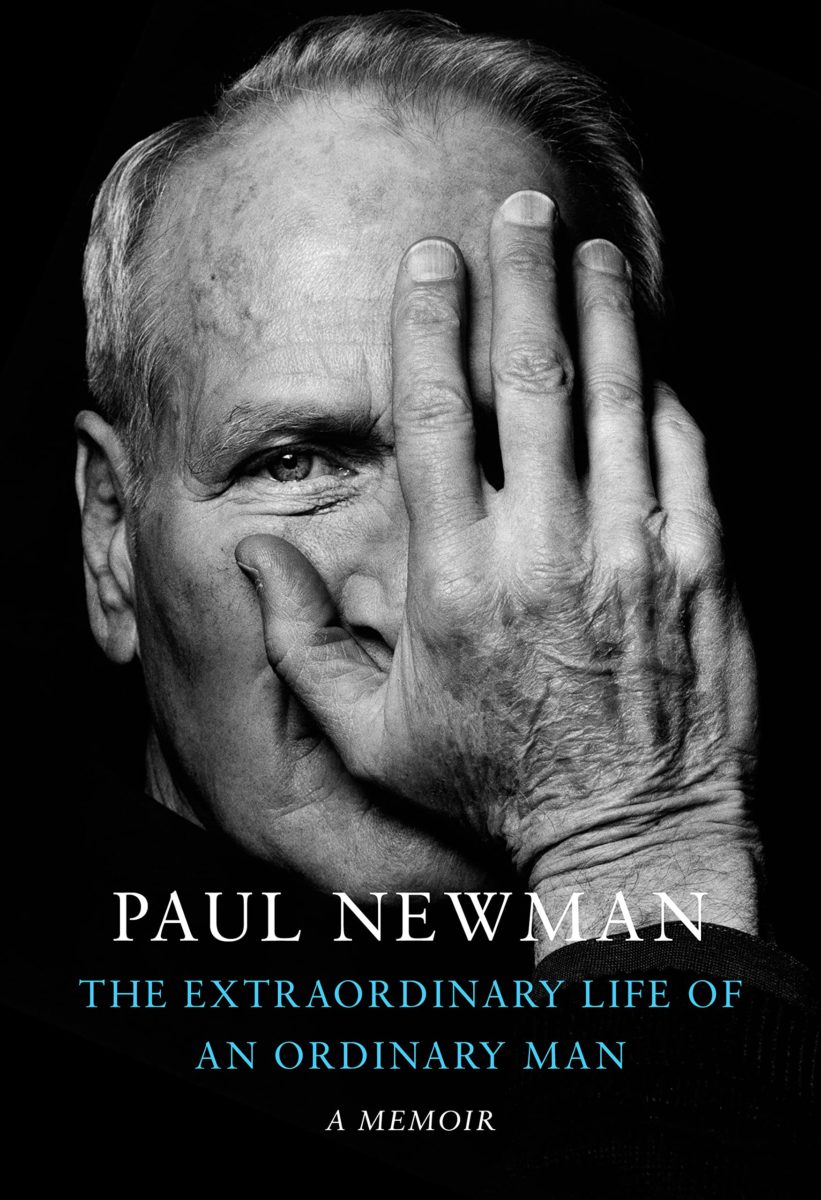

The Extraordinary Life of an Ordinary Man: A Memoir by Paul Newman (Knopf)

The publishing event of the fall is surely the release of The Extraordinary Life of an Ordinary Man, a newly-revealed memoir-slash-“oral history” by the late Paul Newman. Constructed around interviews by the actor’s friend, screenwriter Stewart Stern, and also featuring commentary from the likes of Tom Cruise and George Roy Hill, the result is incredibly revealing. Newman is startlingly self-critical, especially when it comes to his drinking. (“The alcohol helped fuel a sense that you’d accomplished something,” he writes. “Maybe it was a very false sense of accomplishment.”) Whether discussing his long marriage to Joanne Woodward, his love of auto racing, the tragic death of his son, or his troubled relationship with his mother, Newman’s tone is deeply sad. Rarely has a movie star looked in the mirror with such painful honesty. Still, Ordinary Man is not a depressing read. Rather, it’s a genuinely insightful exploration of life from a greatly missed icon, particularly after Ethan Hawke’s series this past summer.

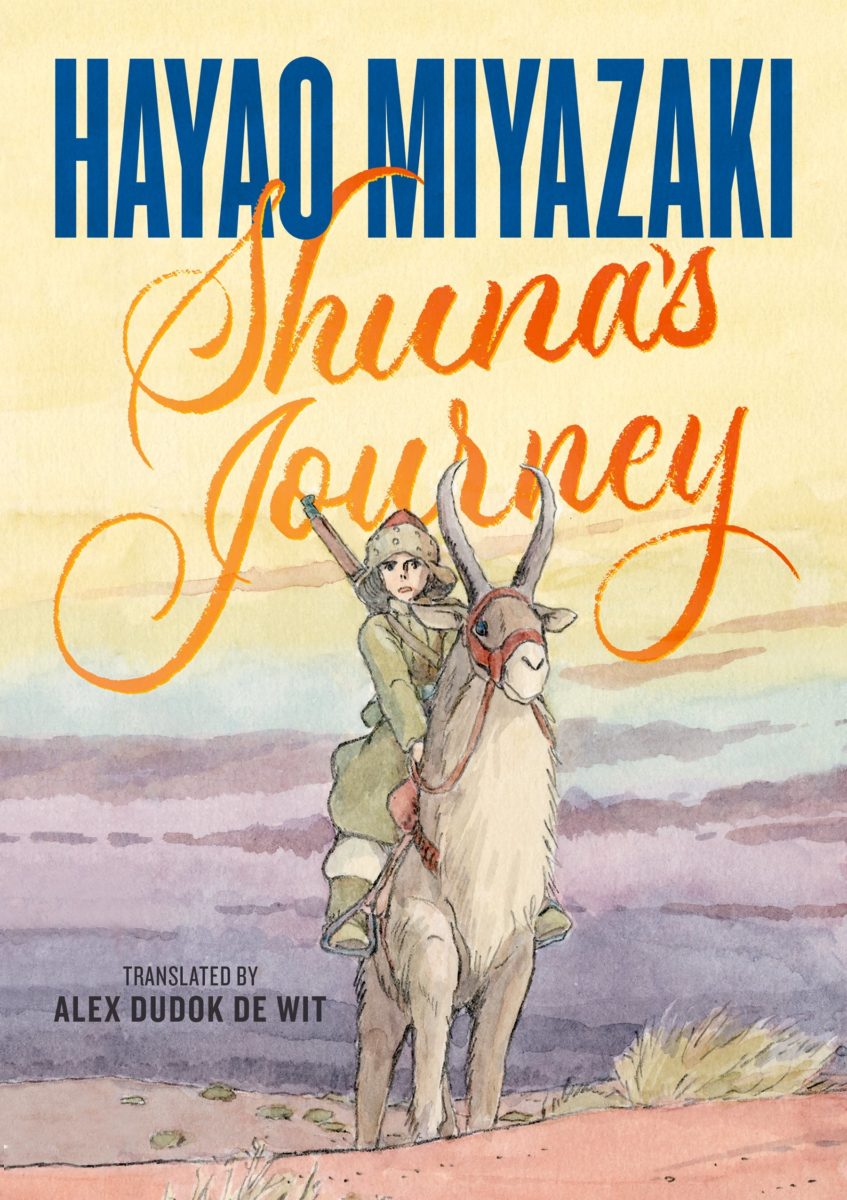

Shuna’s Journey by Hayao Miyazaki (translated by Alex Dudok de Wit) (First Second)

A Hayao Miyazaki release is major news — whether the creation in question is new or not. Shuna’s Journey, a lovely illustrated story from the master filmmaker and artist, was originally published in Japan in 1983. A little less than forty years later, it finally arrives in North America as a hardcover graphic novel, and featuring a translation from Alex Dudok de Wit. Based on a Tibetan folktale, Shuna is the story of a prince seeking to help the impoverished, two sisters held captive, and a harrowing quest. As Dudok de Wit explains in a note at the tale’s start, “Revisiting Shuna’s Journey almost four decades after its publication, we see the seeds of character’s, motifs, and themes that will flourish in Miyazaki’s later works.” Its connections with 1984’s Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind are especially strong. Shuna is both “beguilingly strange,” as Dudok de Wit puts it, and extraordinarily beautiful. Its release is a reason to rejoice.

Road Trip to Nowhere: Hollywood Encounters the Counterculture by Jon Lewis (University of California Press)

In Road Trip to Nowhere, Jon Lewis’ highly engaging book about the explosive (literally, in the case of Zabriskie Point) collision between Hollywood and the counterculture, the author smartly zeroes in on the zeitgeist-altering films and key figures. These include individuals whose lives ended up destroyed (Jean Seberg, Mark Frechette), some whose work was unappreciated for decades (Barbara Loden), a few battle-hardened survivors (Jane Fonda and Dennis Hopper), and one whose odd path is almost incomprehensible (Christopher Jones). Indeed, it is Jones, the star of David Lean’s Ryan’s Daughter, who emerges as Nowhere’s most sadly compelling figure. “Once upon a time in Hollywood, Christopher Jones was a movie star,” Lewis writes. “For the next three decades he did some other things, well out of sight and off the grid. And then without a whole lot of people noticing, he died—by then long lost on his own particular and private road to nowhere.” Beautiful writing, and an essential unpacking of a strange and troubling era.

The Whole Durn Human Comedy: Life According to the Coen Brothers by Joseph McBride (Anthem Press)

This column has featured the indispensable work of film historian Joseph McBride on several occasions, most recently for books on Billy Wilder and Orson Welles. In The Whole Durn Human Comedy, McBride explores the themes of Joel and Ethan Coen, as well as some of the assumptions (and accusations) made about the brothers’ work. “To their detractors,” McBride writes, “the very characteristics that make the Coen Bros. so special are causes of scorn.” As the author points out in the book’s opening, most of the text was completed before the Coens’ rather mysterious split. Knowing this, though, he sees The Ballad of Buster Scruggs as “a culminating work of sorts, a bringing together of their themes and obsessions and the various modes of filmmaking in which they have worked.” It is easy to feel a bit saddened that the partnership that resulted in the likes of Blood Simple, Miller’s Crossing, Fargo, No Country for Old Men, and Inside Llewyn Davis is no more––at least for now. Still, as McBride demonstrates throughout the book, we’ll always have these films and more to watch, analyze, debate, and treasure.

99 Movie Crosswords edited by Anna Shechtman (A24)

As of this writing, A24’s delightful crosswords collection, 99 Movie Crosswords, is sold out. My advice? Keep checking, since the $34 book is an absolute blast. I’m a crosswords novice, but my absurd film knowledge caused me to jump right to the “expert” section … and then back to the “neophyte” section. (I found every puzzle here *extremely* difficult but also very, very fun.) Puzzle titles include “Miyazaki Magic,” “The World of Elaine May,” “Macguffins,” and “As Godard Said.” From start to finish, the book—edited by writer Anna Shechtman and featuring puzzles made in collaboration with the likes of Jenny Slate, Tim Heidecker, and David Lowery—is a total joy. But it ain’t easy.

Christopher Nolan: The Iconic Filmmaker and His Work by Ian Nathan (White Lion)

The shelf of deep-dives into the films of Christopher Nolan continues to grow. The latest, from Ian Nathan, smartly attempts to explain why it is so difficult to classify a filmmaker whose work is often unclassifiable. “He defies categories, even nationalities,” writes Nathan. “He crosses the streams of artist and scientist, entertainer and provocateur, lone wolf and one of the cool set. He has defined millennial Hollywood, yet stands apart from the crowd.” Nathan’s discussion of Tenet is especially strong; he finds great poignance in the utterance of Clémence Poésy’s scientist early in the film: “Don’t try to understand it. Feel it.” This, Nathan believes, is a “sly instruction on Nolan’s behalf to the audience. Resist the urge to figure things out. Make a leap of faith.” Where Nolan’s upcoming Oppenheimer will fit with the rest remains to be seen—as Nathan explains near the book’s end, Robert Oppenheimer is a “strange and elusive target.” Sounds like an appropriate subject for Christopher Nolan.

Fly By Night by Steve Chain (Trine Day)

One of the few Spielberg entries not analyzed in the aforementioned Citizen Spielberg is his segment in Twilight Zone: The Movie. It tends to be forgotten, as the project was overshadowed due to the horrific deaths of actor Vic Morrow and two children on the set of John Landis’ segment. In Fly By Night, journalist Steve Chain takes a hard-hitting investigative approach to the sordid story, and it makes for a riveting, upsetting read. No one involved comes off well. What is particularly sad is how the Hollywood heavyweights involved moved on with few consequences. Note that the book contains extremely graphic photos, including shots of the accident’s appalling aftermath.

Tesla: All My Dreams Are True by Michael Almereyda (OR Books)

I was not sure what to make of director Michael Almereyda’s Tesla upon release; the offbeat story of inventor Nikola Tesla plays as a sort of anti-biopic, upending audience expectations at every turn. Weeks later, however, I found myself thinking back to Tesla and chuckling over its brilliance. Just as impressive is Almereyda’s Tesla: All My Dreams Are True, an exploration of how the film came to be, why choices were made, and how it fits in the filmmaker’s unique oeuvre. The book is both wildly funny and full of fascinating tidbits. For example, Almereyda recounts how his Nadja backer (and actor) David Lynch at one point pursued a Broadway production about Tesla, with Liam Neeson in the lead. (Eli Roth was employed as an “undercover research assistant, pursuing Tesla lore and arcana on and off for five years.”) More somber is Almereyda’s encounter with late Zappos founder Tony Hsieh, just a few months before his strange death. It is no exaggeration to say that Tesla is unlike any biopic ever made—and Tesla: All My Dreams Are True is unlike any “making of” ever written.

Mental Floss: The Curious Movie Buff by Jennifer M. Wood (Weldon Owen)

The Mental Floss gang can always be counted on for enjoyable lists and conversation-starters. The Curious Movie Buff has plenty of both. It must be noted that the book is not exactly written for cinema die-hards, although they, too, will find it to be a pleasant diversion. This one is more for folks who scroll endlessly through Netflix and end up, well, scrolling some more. In her introduction, Jennifer M. Wood explains that the text aims to provide readers “with dozens of new-to-you films to add to your various queues.” And any collection that opens with All That Jazz and ends with Zodiac is A-OK in my book.

The Cinema House and the World: The Cahiers Du Cinema Years, 1962–1981 by Serge Daney (MIT Press)

Perhaps the most essential text in this rundown is The Cinema House and the World. This 500-plus page collection of the writings of Daney, the late Cahiers Du Cinema editor, is sprawling, complex, and unforgettable. As A.S. Hamrah puts it in the book’s introduction, “Daney was perhaps the magazine’s last great editor. While he was there, Cahiers maintained its opposition to commercial cinema without abandoning its analysis of it.” There are films championed here by Daney that still await widespread discovery, and concepts that leave the reader—so many years later—downright shaken by its author’s level of insight. Above all else, Cinema House leaves us spellbound by Daney’s critical approach, one steeped in psychoanalysis. He died in 1992 of AIDS-related causes, but left behind writing that is both engaging and challenging.

Black Hollywood: Reimagining Iconic Movie Moments by Carell Augustus (Sourcebooks)

Rethinking legendary film and television series, as well as legendary performers, with freshness and verve is no easy task. However, the photo book Black Hollywood: Reimagining Iconic Movie Moments succeeds, big-time. The foreword by Forest Whitaker and afterword by Niecy Nash are insightful, but it is the photography of Carell Augustus that stands out. Some are joyful (Amber Stevens West in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, Dulé Hill in Singin’ in the Rain), others boldly humorous (Jay Ellis in American Psycho, Eugene Byrd in The 40-Year-Old Virgin). And a few serve as teasers for reimaginings that with any luck might come to exist someday (Lauren London in Basic Instinct, Fonzworth Bentley and Faune Chambers as The Avengers’ John Steed and Emma Peel).

The Empire of Effects: Industrial Light & Magic and the Rendering of Realism by Julie A. Turnock (University of Texas Press, Austin)

Author Julie A. Turnock finds new ground to cover in The Empire of Effects: Industrial Light & Magic and the Rendering of Realism, a captivating look at digital realism and the success of ILM. She is interested less in the history of ILM, which has been covered many times before, and instead considers how changes in effects style have modified audience expectations—for better and worse. Turnock astutely analyzes the “aesthetic joining of Marvel and ILM” via Jon Favreau’s Iron Man, and sees “Favreau’s personal preferences” as having had a major impact on modern blockbuster aesthetics: “Before the MCU films, ILM had set the style for effects realism and strongly encouraged other companies to adapt their style. What was initially an unspoken but ILM-led standard up to about 2010, what I call the ‘IL style of effects realism,’ Disney co-opted by way of Marvel Studios into a style that all effects companies had to adopt to compete for jobs.”

Viva Hollywood: The Legacy of Latin and Hispanic Artists in American Film by Luis I. Reyes and TCM Underground: 50 Must-See Films from the World of Classic Cult and Late-Night Cinema by Millie De Chirico and Quatoyiah Murry (Running Press)

TCM and Running Press regularly release illuminating books about Hollywood classics, legends, and lore. The latest two are fine additions. Viva Hollywood is a comprehensive accounting of the achievements of Latino and Hispanic performers and filmmakers and includes newer stars but also important figures like Dolores Del Rio and Katy Jurado. And TCM Underground is a must-own for those of us who have spent many late nights watching the TCM series of the same name. In his foreword, Patton Oswalt describes the book as one that is not made to be read from the beginning—“Flip around, stop where it grabs you, let it lead you backward and forward and sideways.” He nicely captures the feel of stumbling upon films like Two-Lane Blacktop, The Brood, and, yes, Mac & Me. The authors’ description of Mac’s infamous McDonald’s commercial “that interrupts the film for no natural reason” ends with a line that many of us say or think when watching cult cinema: “Thank the movie gods!”

Black Panther (21st Century Film Essentials) by Scott Bukatman (University of Texas Press) and Black Panther: Dreams of Wakanda (Del Rey)

There has been no fall blockbuster more eagerly anticipated than Ryan Coogler’s Black Panther: Wakanda Forever—I’m calling Avatar: The Way of Water a winter release—and two new books adroitly discuss the impact of the first film and its eponymous hero. In Black Panther (21st Century Film Essentials, Scott Bukatman unpacks this cultural phenomenon and its afterlife. Following the murder of George Floyd, the Black Lives Matter movement, and the death if star Chadwick Boseman, Bukatman says Black Panther became an ‘Important’ movie, one that surely deserved more than my usual ruminations on fun fantasies of flying bodies. Race could no longer be just one element among others to explore; now it needed to be at the center.” Similarly, Dreams of Wakanda grapples with the film via essays from journalists, academics, and folks involved with the film and comics. Together, these two books offer new ways to read and understand what Black Panther truly means to audiences.

The Academy and the Award by Bruce Davis (Brandeis University Press)

Yes, here we are again, deep into another awards season. (Yay?) While the Academy Awards often seem ridiculously riddled with WTF-ness (see last year’s Oscars Cheer Moment), Bruce Davis shows that this is nothing new. In the author’s The Academy and the Award, Davis studies the early days of the Oscars and finds that the Academy “was never the serene, opulent, Olympian assemblage that movie lovers might have imagined. There was never a shortage of troublesome issues for the organization.” Will Hays’ hero complex, the Kazan controversy—it is all here, and explained by Davis with great wit and keen insight.

Stephen King: A Complete Exploration of His Work, Life, and Influences by Bev Vincent (Epic Ink)

Author Bev Vincent’s Complete Exploration of the life and work of Stephen King was released in September, just as the master of terror celebrated his 75th birthday. It is a fitting tribute—comprehensive, full of surprising details, and packed with reminders that nobody does it better than King. Also included is unique ephemera, including the original title layout page for The Stand, a glimpse at the handwritten manuscript page for Cujo, and the call sheet from the filming of King’s role in Creepshow. It’s a blast to open the book at random and dive in, and Vincent ensures every King text receives its just due.

The Art of Star Wars: The High Republic (Volume One) by Kristin Baver (Abrams Books)

The Star Wars universe has seen its share of highs and lows in the last several years, but one undebatable success is LucasFilm Publishing’s High Republic series. Especially strong are the covers of books like Light of the Jedi. The series designs are the focus of The Art of Star Wars: The High Republic, another handsome release from Abrams Books. In addition to backstories that detail the creation of the series, we have detailed looks at characters like the Wookie Jedi Burryaga. “He’s just Burryaga, like Cher or Sting,” adds LucasFilm Publishing Director Michael Siglain, helpfully. The artwork herein shows that many High Republic-related pleasures still await the Star Wars faithful.

The MGM Effect and The 50 MGM Films That Transformed Hollywood by Steven Bingen (Lyons Press)

Steven Bingen must be considered the MGM expert, although he has also written about Warner Bros. and Paramount. The MGM Effect and 50 MGM Films That Transformed Hollywood are his second and third books on the studio whose roaring lion, he states, “is the most recognized corporate symbol in the world.” That worldwide impact is the focus of Effect, which also considers “the other MGMs” (including what was once called Disney-MGM Studios in Orlando) and how the studio has been featured in various films and cartoons. Meanwhile, 50 MGM Films catalogs everything from Greed to Get Shorty. The latter, a 1995 MGM release, “ends with Chili [Palmer] and company walking out the doors of a soundstage and the camera pulling up to reveal … MGM.”

Vedder, Bono, Dylan, and 75 years of Bowie — new music books:

There is no one writing about music with more passion and intellect than Steven Hyden. His latest, Long Road: Pearl Jam and the Soundtrack of a Generation (Hachette Books), somehow manages to top Hyden’s 2020 masterpiece, This Isn’t Happening: Radiohead’s “Kid A” and the Beginning of the 21st Century. Over the course of Long Road, Hyden traces the highs, lows and, ultimately, the on-stage renaissance of Eddie Vedder and company through an exploration of 18 key songs. Long Road is far more insightful than Cameron Crow’s Pearl Jam Twenty documentary; in fact, I’ve already read it twice. Hyden also posits fresh theories throughout, on Vedder’s relationship with fandom and his bandmates and, in one captivating section, on Stone Temple Pilots as a sort of alternate-universe, “what if?” Pearl Jam: “The story of Scott Weiland and Stone Temple Pilots fascinates me in the context of Pearl Jam because STP is like the bizarro version of Pearl Jam.” If that intrigues you, and you grew up with Ten, Long Road is a must-read.

It was only a matter of time before U2 frontman Bono joined the ranks of Springsteen and Patti Smith by writing a memoir. What is perhaps surprising, though, is the format of Surrender: 40 Songs, One Story (Knopf). Not unlike Long Road, each of the book’s forty chapters is named after (and centered around, to some degree) a different song. It is to Bono’s credit that the choices stray beyond the obvious. Yes, “With or Without You” and “One” are featured, but so, too, are “Wake Up Dead Man,” “Breathe,” and “Cedarwood Road.” Throughout, Bono writes with wit and much self-deprecation; consider his remarks on the underrated Pop: “When it’s finished—and it was never finished—Pop is not the party we were looking for. It’s the hangover after the party.” And much of the text, of course, involves his activism. The U2 haters will not be swayed, but anyone who grew up adoring The Joshua Tree and Achtung Baby will be more than satisfied.

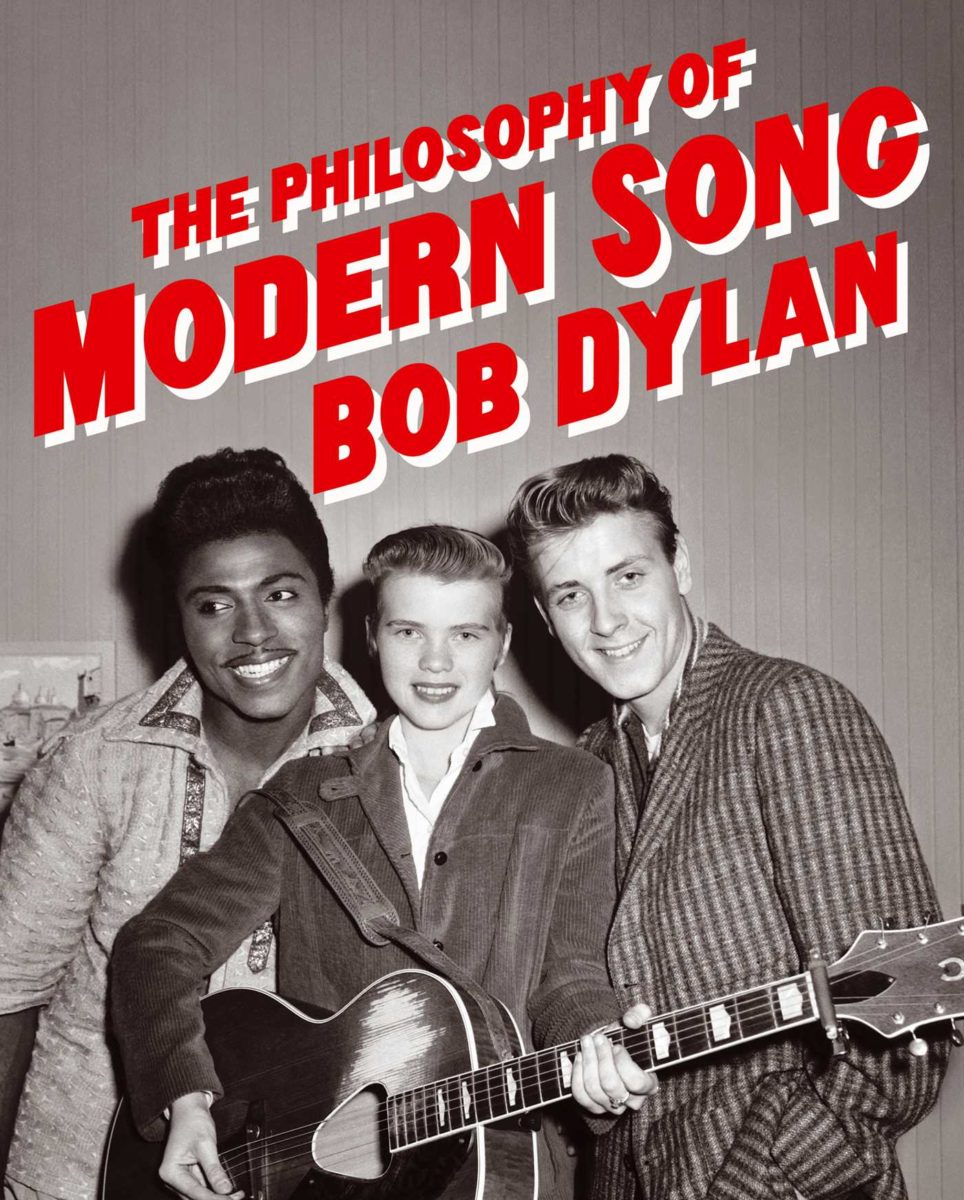

Bob Dylan’s The Philosophy of Modern Song (Simon & Schuster) is—I kid you not—even more compelling than Chronicles, Dylan’s 2004 memoir. Featuring more than 60 essays, each centered around a song, Philosophy feels both deeply personal and startlingly incisive. Consider these lines Dylan’s take on the Clash’s “London Calling”: “The Clash have nothing but disdain for Beatlemania. The adolescent and extreme emotions of the awkward age. ‘I Wanna Hold Your Hand,’ all the theme songs for Little Missy and the school maids, sweet-little-sixteen mania, have no place in the real London anymore.”

David Bowie has been on our minds even more than usual in the last few months. He would have been 75 this year, and in addition to the wonderful documentary Moonage Daydream comes Bowie at 75 by Martin Popoff (Motorbooks) and I’m Not a Film Star: David Bowie as Actor, edited by Ian Dixon and Brendan Black (Bloomsbury). Bowie at 75 is an absolute stunner—a 200-page, photo-heavy hardcover accounting of the icon’s entire life and career. The text is sharp and at-times surprisingly critical (re: the underrated Earthling: “Who’s responsible for this love-it-hate-it record?”). Above all else, though, it is the photography and scores of memorabilia seen throughout that will engage the Bowie faithful. And Film Star is the most complete look yet at Bowie’s roles in cinema. Of particular interest are unique studies of his performance as Pontius Pilate in Scorsese’s Last Temptation of Christ and his final return to the world of The Man Who Fell to Earth via the musical Lazarus. As essayist Denis Flannery explains, “Lazarus (2015) depends for its existence on a melancholic relationship to cinema.”

Books for kids, tweens, and teens with an interest in cinema

Past readers of this column may recall A Is for Auteur, which was featured in November 2020. This visually delightful introduction to cinema for kiddos—written by Cory Everett and illustrated by Steve Isaacs—was just the beginning. My First Movie is a three-part series diving even deeper, written once again by Everett, who teamed with illustrator Julie Olivi. My First Giallo Horror, My First French New Wave, and My First Film Noir (‘lil cinephile) can be purchased individually or packaged together in a limited-edition cardboard slipcase. Clearly, the ’lil cinephile series will be offering more treats in the years to come, and thank goodness—the kids have to learn about profondo rosso, le novelle vague, and femme fatales sooner or later.

In my house, we watch the Harry Potter films multiple times each year. And as my kids and I re-work our way through the saga, I’m invariably impressed with the performance of Tom Felton. The actor is especially strong in Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince. Felton’s memoir, Beyond the Wand (Grand Central Publishing), shows Felton to have an innate understanding of his fame. “I try to remind myself every day how lucky I am to have my life,” he writes. Felton shares lovely stories from the Potter sets, and also discusses a stint in rehab with refreshing candor.

Speaking of my household’s viewing habits, my kids recently watched the entirety of the Minions series—The Rise of Gru was by far the worst, IMO—and afterwards enjoyed paging through The Art of Eric Guillon by Ben Croll (Insight Editions). It features sketches and concept art from all of the French artist’s Illumination films, which also include Dr. Seuss’ The Lorax and Sing. Guillon’s designs for The Secret Life of Pets are far more enthralling than the resulting film. Disney Princess: Beyond the Tiara: The Stories. The Influence. The Legacy. by Emily Zemler (Epic Ink) is a visual treat that also details the origins for the look of characters like Aurora and Ariel. It belongs on the shelf of any Disney fanatic or collector.

Jurassic World: The Ultimate Visual History (Insight Editions) by James Mottram is not for kids, per se, but budding young film fanatics should find the book as enticing as I found 1993’s The Making of Jurassic Park by Don Shay as a 13-year-old. Even with my personal disappointment with Jurassic World Dominion, I found Visual History to be quite absorbing. It offers a comprehensive outline of some of the controversial decisions made for the second Jurassic trilogy, as well as a solid distillation of story and design decisions.

Star Wars: Galaxy’s Edge: Treasures from Batuu by Riley Silverman (Insight Editions) offers the backstory for Walt Disney World rides like Smuggler’s Run, and also includes some cheeky souvenir items (including a Black Spire Outpost translator, a map, buttons, and stickers). Lastly, outside of the performances of Brendan Fraser and Sadie Sink, I was not a fan of Darren Aronofsky’s The Whale when I saw it at TIFF. However, his first novel (co-written with Ari Handel) is a gem. Monster Club (Harper) delighted me with its story of a role-playing game come to life, as well as my Stranger Things-loving 12-year-old. This is book one in a series; fingers crossed that Aronofsky will bring it to the big (or small) screen at some point.

More noteworthy reads:

Along with Paul Newman’s Extraordinary Life, the recent memoir I found most engaging is Life’s Work: A Memoir by David Milch (Random House). The Deadwood and NYPD Blue creator’s rough-and-tumble story of childhood in Buffalo, life as an in-demand television writer, and devastating gambling losses is, at times, painful to read. However, Milch tackles it all with his typically brilliant self-deprecation and intelligence. Incidentally, I found the most compelling Hollywood stories here to be Milch’s accounts of two troubled projects: John From Cincinnati and Luck.

A rave New York Times review drew me to Bold Ventures: Thirteen Tales of Architectural Tragedy by Charlotte Van den Broeck (Other Press), an analysis of buildings whose architects are known (or rumored) to have committed suicide as a result of the failure of their creations. Van den Broeck writes with startling clarity and a uniquely personal POV. In the Houses of Their Dead: The Lincolns, the Booths, and the Spirits (LiveRight) by Terry Alford studies the superstitions and spiritual interests of Abraham Lincoln and others. The most resonant figure in Alford’s uniquely compelling study turns out to be the widowed First Lady, Mary Todd Lincoln. Her haunted final years are sad and upsetting. Both Ventures and Houses have a strongly cinematic feel.

In As It Turns Out: Thinking About Edie and Andy (Farrar, Straus and Giroux), the sister of Edie Sedgwick takes a revealing look at the icon’s short life and complex relationship with Andy Warhol. Alice Sedgwick Wohl writes with a healthy respect for Edie, while also being honest with her own complex feelings toward her late sibling: “Edie herself has always been wholly relevant. It remains unclear, at least to me, what it was that made her extraordinary.” Down and Out in Paradise: The Life of Anthony Bourdain by Charles Leerhsen (Simon & Schuster) is already controversial, specifically for its grim accounting of the relationship between Bourdain and actress Asia Argento. Reading the somber details, it is easy to see why this unauthorized bio has drawn many jeers. However, that is just one section of an exhaustively researched book. The Bourdain of Down and Out is brilliant, volatile, and haunted by his fame and demons.

For a palette cleanser, pick up Charles M. Schulz: The Art and Life of the Peanuts Creator in 100 Objects by Benjamin L. Clark and Nat Gertler (Weldon Owen). The coffee table book is a treasure trove of old comic strips, merchandise, and items that inspired the genius cartoonist. The foreword features a conversation with Wes Anderson, who states, “I don’t think I’ve ever deliberately/specifically wanted to allude to Peanuts in any of my movies—but I have always found myself openly stealing from it anyway.”

New novels:

Planning on a novel or two as a holiday gift? The selections here are all make fine presents, for yourself or others. For fans of Glass Onion’s genius detective Benoit Blanc, I recommend The Enigma of Room 622 by Joël Dicker (Harper Via). The Swiss novelist’s latest is a meta mystery (its protagonist is a writer named Joël Dicker) set at a deadly luxury hotel in the Alps. It kept me guessing, but perhaps Blanc would decipher things quicker than moi. Tess Gunty’s The Rabbit Hutch (Knopf) is a somber but ingenious debut taking place in a decaying apartment building in the Midwest. And Cinephiles awaiting Damien Chazelle’s Babylon will devour Mercury Pictures Presents by Anthony Marra (Hogarth). The suitably epic, pre-World War II-set tale of an Italian immigrant turned associate producer at a Hollywood studio is moving and witty.

Some major names released novels in recent months, none bigger than Stephen King. His latest, Fairy Tale, is a fantasy adventure centered on a teenager who enters another world. It’s King’s most downright joyful novel in years; it’s no wonder that the film rights sold quickly. (Paul Greengrass will direct.) Room and The Wonder author Emma Donoghue is no stranger to adaptation, and it would be no surprise to eventually see a film of Haven (Little, Brown). Its tale of young monks on a quest for survival is truly harrowing. Charlie Kaufman’s adaptation of Iain Reid’s I’m Thinking of Ending Things was one of 2020’s finest films, and it would be a treat to see the filmmaker take on Reid’s newest mindbender, We Spread (Scout Press). It is about an elderly woman in an assisted living facility in the same way that I’m Thinking of Ending Things is about a young couple on a road trip. In other words, prepare to be shaken.

If those last two novels sound a bit heavy for the holiday season, I have three more recommendations. The Princess and the Scoundrel by Beth Revis (Del Rey) is a delightful Star Wars novel about the wedding (and danger-filled) honeymoon of Han Solo and Princess Leia Organa. The Other Guest by Helen Cooper (Putnam) feels like a beach read, but the central mystery — a woman returns to the resort in which her niece died and finds that her family has moved on completely — is wonderfully puzzling any time of year. And The Swell by Allie Reynolds (G. P. Putnam’s Sons) is quite literally a beach read, and offers an action-heavy plot centered on surfers who live very dangerously. Pick it up for the Point Break fan in your life.

New to Blu-ray and 4K:

The most noteworthy Blu-ray/4K release of late must be David Lynch’s Lost Highway (Criterion). Fred Madison’s fugue state has never looked so gorgeous or frightening, and the release even includes the entirety of Pretty as a Picture: The Art of David Lynch, Toby Keeler’s fine 1997 documentary. In addition, the booklet features an excerpt from Chris Rodley’s Lynch on Lynch. Speaking of films that were treated with injustice upon release, Kino Lorber’s Blu-ray edition of the infamous Bruce Willis flop Hudson Hawk will hopefully lead to some reassessment. After all, some, like the incomparable Richard Brody, have argued that Michael Lehman’s caper comedy offers numerous joys. The director contributes audio commentary to the release. Meanwhile, as we move deeper into awards season chatter, re-watching Elvis (Warner Bros. Home Entertainment) at home should serve as a reminder that Austin Butler is a revelation as the King; the Blu-ray and 4K offer a number of making-of featurettes. And it is a lovely time to be a Brian De Palma fan, as two of his finest—Blow Out and Dressed to Kill—have been released on 4K by Criterion and Kino Lorber, respectively. Blow Out includes an essay by critic Michael Sragow as well as the film’s original New Yorker review from De Palma supporter Pauline Kael. And Dressed to Kill offers a bevy of features, including new interviews with Keith Gordon and Nancy Allen. I dare you to watch it with the family this December.