Welcome to 2024! This, our first column of the new year, follows Spielberg: The First Ten Years by Laurent Bouzereau (Insight Editions) and Steven Spielberg: All the Films by Olivier Bousquet, Arnaud Devillard, and Nicolas Schaller (Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers)

I am not sure what Steven Spielberg obsessives like myself did to earn two lengthy, photo-backed, hardcover career appreciations, but I’m not complaining. Steven Spielberg: All the Films runs for nearly 500 pages and covers literally everything, from the director’s contributions to Rod Serling’s Night Gallery to The Fabelmans. Along the way are some unique insights, surprising facts (Leonardo DiCaprio was approached to play Tintin?), and the inclusion of some of his 1980s television work. And Spielberg: The First Ten Years is just as engaging, and even more in-depth. It is authored by Laurent Bouzereau, who we know for his behind-the-scenes production documentaries on Spielberg’s films. Bouzereau brings that same passion for the process of filmmaking to this text covering Duel, The Sugarland Express, Jaws, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, 1941, Raiders of the Lost Ark, and E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial. “Those first ten years of his career informed the years that followed — the humanity, complexity, and thematic depth of his stories becoming a constant in his work,” he writes. Featuring interviews with the director and detailed analysis, Ten Years makes a compelling case that Spielberg’s run from 1971 to 1982 is downright unparalleled.

The Path to Paradise: A Francis Ford Coppola Story by Sam Wasson (Harper)

Author Sam Wasson’s 2020 book about the creation and legacy of Polanski’s Chinatown, titled The Big Goodbye, was a knockout. His new look at the dreams, failures, and ultimate redemption of Francis Ford Coppola is just as absorbing. What makes The Path to Paradise so refreshing is its focus. Rather than simply rehashing the oft-told tales of making The Godfather, Wasson covers the American Zoetrope experience — the still-shocking making of Apocalypse Now, the unjust failure of One From the Heart, and, finally, Coppola’s rebirth as a businessman and director. Therefore, we learn a bit about Megalopolis, and, yes, there is plenty of Godfather, too. As Coppola tells Wasson during the production of Megalopolis, “I’m not making the film. It’s making itself.” Spoken like a true visionary.

MCU: The Reign of Marvel Studios by Joanna Robinson, Dave Gonzales, and Gavin Edwards (Liveright)

In a strange way, the timing for the release of MCU: The Reign of Marvel Studios could not be better. Following the failure of The Marvels and the shrugs which greeted Ant-Man and the Wasp: Quantumania and TV’s Secret Invasion, the studio is at an intriguing crossroads. As Robinson, Gonzales, and Edwards show, though, this is not the first time Kevin Feige and company have faced peril. See, for example, the complex production of Iron Man, the loss of Edgar Wright as director of Ant-Man (the details of this are captivating, and shed much light on the filmmaker-unfriendly Marvel process), and the death of Chadwick Boseman. One of the lessons of MCU? Do not count out Feige.

Todd Haynes times two: I’m Not There (21st Century Film Essentials) by Noah Tsika (University of Texas Press) and Todd Haynes: Rapturous Process (Museum of the Moving Image)

Todd Haynes’ latest, May December, was one of the most memorable and provocative films of 2023. It is nice, then, to see Haynes in the spotlight once again, especially since his last two narrative features, Wonderstruck and Dark Waters, were greeted with muted praise. In I’m Not There (21st Century Film Essentials), Noah Tsika analyzes Haynes’ audacious 2007 Bob Dylan (sort of) biopic, which the author believes “is perhaps the least studied” of the director’s films. The text establishes, however, that the film is more than worthy of deep consideration. Tsika even details how the film connects with Haynes’ career-long battles with trademark and copyright issues. All told, this is a truly essential study of a film that seems even bolder now than it did in 2007. Meanwhile, Rapturous Process was published by the Museum of the Moving Image on the occasion of its retrospective and exhibit dedicated to Haynes. It is a gorgeous book, loaded with interviews, essays, and art from Haynes’ personal archives. His childhood sketches of Lucille Ball clearly connect to his 1993 short, Dottie Gets Spanked.

Legends of Old Hollywood

A number of recent releases explore some of the most legendary figures in entertainment history. Let’s start with two icons whose lives have inspired shelves upon shelves of books: Charlie Chaplin and Alfred Hitchcock.

Hitchcock’s Blondes (Putnam) by Laurence Leamer is as spicy as one might expect given its title. But there is more to it than movieland gossip. There are the expected stories of Hitchcock’s lust for starlets like Tippi Hedren. But there is also great emotion in Leamer’s writing, especially Hitchcock’s surprising reaction during his AFI tribute in March 1979. Notorious star Ingrid Bergman presented Hitch with “the key” from the film: “Bergman handed the key to Hitchcock and kissed him on the cheeks. Then in a motion that was spontaneous, deep, and true, she hugged him. Although Hitchcock did not like people to touch him, he reached out with his arms and enveloped the actress. Hitchcock was embracing not just Bergman but life itself.” It is a lovely moment in a book that is full of spice, yes, but also an unexpected amount of sugar.

For several weeks now, I’ve been reading Charlie Chaplin vs. America: When Art, Sex, and Politics Collided by Scott Eyman (Simon & Schuster)—and I am purposely taking my time. This is the most affecting book about Chaplin that I’ve read, and the one that feels most connected to the age we live in. “[U]nderneath the flashes of anger, Chaplin never lost his underlying affection for the country where he spent most of his life,” Eyman writes. “America gave him opportunity, wealth, and position. If more than a decade of impeccably targeted character assassination nudged the public into thinking Charlie Chaplin was more trouble than he was worth, he believed the ledger still came out on the positive side.”

George Hurrell’s Hollywood: Glamour Portraits 1925-1992 by Mark A. Vieira (Running Press) is a gorgeous collection of photographs from the artist Sharon Stone calls “a master of light, elegance, and glamour.” Indeed, Hurrell’s portrait of Stone wearing a leopard and lying on a saber-tooth tiger rug is quite striking. That is a more modern Hurrell shot, but the photos that truly resonate here are the portraits of bygone icons—Joan Crawford, Marlene Dietrich, Jane Russell, Paulette Goddard. This book is a breathtaking collection of images.

Similarly impressive is Edith Head: The Fifty-Year Career of Hollywood’s Greatest Costume Designer by Jay Jorgensen (Running Press). It offers a lengthy (more than 300 pages) and fitting tribute to the name that was synonymous with costume design for five decades. “This book isn’t so much a biography of Edith Head, the woman, but more of a biography of the clothes that she designed,” writes another legendary costume designer, Sandy Powell, in her foreword. The photos are, in a word, stunning, and so is the cover of A.K.A. Lucy: The Dynamic and Determined Life of Lucille Ball by Sarah Royal (Running Press). The shot of a glamorous Ball is a reminder that there was far more to Lucy than her classic TV series. A.K.A. Lucy is a comprehensive look at an incredibly successful life and career.

Daughter of the Dragon: Anna May Wong’s Rendezvous With American History (Liveright) by Yunte Huang is an exhaustive and compelling look at the first Chinese-American Hollywood star, while Lena Horne by Donald Bogle (Running Press and TCM Library) is a comprehensive biography of Hollywood’s first African American movie goddess, a figure whose influence is clearly evident today. And Helen of Troy in Hollywood by Ruby Blondell (Princeton University Press) is a smart exploration of how this mythic figure has been portrayed in film and television. Blomndell has written a thematically bold book that entertainingly contemplates what Helen of Troy signifies in old and modern Hollywood productions.

New music books

I’m not sure there is a funnier recent music book than 60 Songs That Explain the ’90s by Rob Harvilla (Twelve). Harvilla includes my favorites (Oasis! The Verve!) and yours, and does so in tremendously witty fashion. Here he is on the controversy that greeted the Prodigy’s “Firestarter” video after it aired for the first time on the BBC in 1996: “[S]tuffy, scandalized, monocle-wearing English people were basically just calling the BCC and going, Please get that scary-looking arsonist man off my television. Which is fantastic, even if it is mythologizing music-industry bullshit.”

I have always found Barbra Streisand to be a beguiling figure—blazingly creative and fiercely intelligent, and always true to herself. Streisand’s years in the making memoir, My Name Is Barbra (Viking), demonstrates that she is also extremely wise. The 900-page (!) book is full of pearls about her career, but what is most intriguing here is her no-nonsense approach to her career. Streisand is self-critical in My Name Is Barbra, but she is also unafraid to call out those who let her down or stood in her way. Take, for example, her words about Martin Ritt, director of 1987 thriller Nuts: “Marty never quite understood this film. He had been handed a finished script, and he would carry it around on set. But I helped write that script. I knew every scene and why it was there.” Guess what? She was right, and Streisand’s instincts would have made for a better film. There are scores of moments like this in My Name Is, and they help make it one of the finest entertainer memoirs I’ve ever read.

Bridge and Tunnel Boys: Bruce Springsteen, Billy Joel, and the Metropolitan Sound of the American Century (Rutgers University Press) by Jim Cullen ponders the connections and similarities between Springsteen and Joel, and this makes for an astute and often surprising read. While there is no debating the significance of the Boss, Cullen successfully makes the reader reconsider the value of Joel’s life and work, as well.

The Who & Quadrophenia by Martin Popoff (Motorbooks) is a colorful tribute to an album that is appreciated more now than it was upon release in 1973. The book coincides with Quadrophenia‘s fiftieth anniversary, and while it spends a great deal of time on the album’s creation, release, and afterlife, its 1979 film adaptation is also highlighted.

Madonna: A Rebel Life (Little, Brown) by Mary Gabriel is the best biography of the Queen of Pop to date. Gabriel’s research is deep, and her understanding of Madonna’s significance as an artist and a woman is strong. The book concludes in fitting fashion, onstage in London: “Racked with pain, as she pushed her way through the crowd, fist-bumping fans, her determination was as clear as her message. Fight on.” Indeed, the book argues that no modern performer has fought for her vision as fiercely as Madonna.

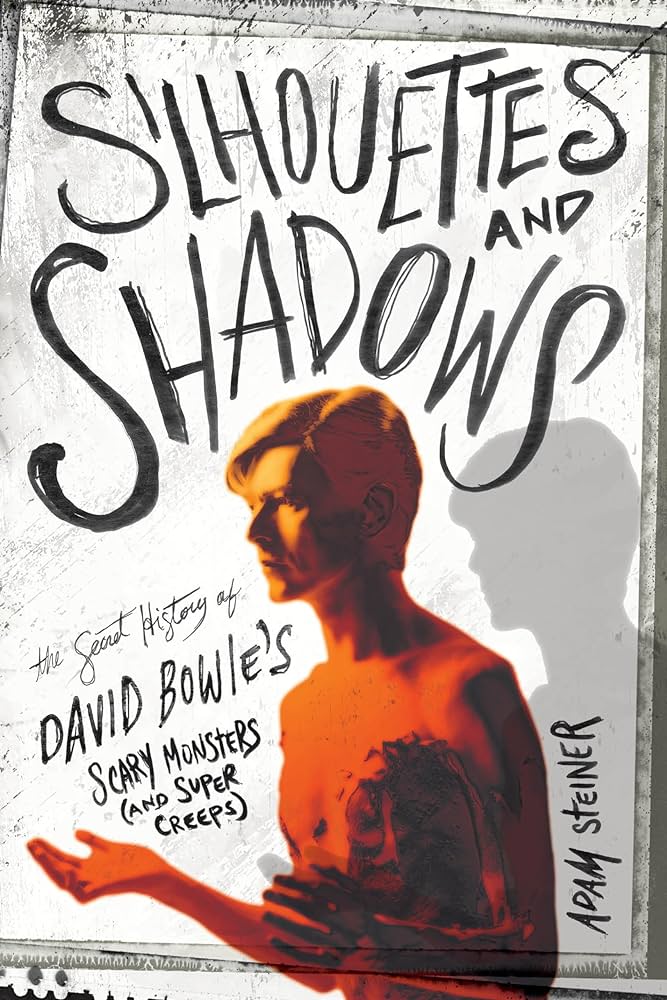

David Bowie was, of course, one of Madonna’s greatest influences. Silhouettes and Shadows: The Secret History of David Bowie’s Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) (Backbeat Books) by Adam Steiner is a refreshing look at a Bowie album that has often been overlooked due to its positioning between his classic Berlin Trilogy and blockbuster Let’s Dance. Steiner argues that Scary Monsters “would come to be the album that crowned Bowie’s 1970s while heralding the emerging new sounds of the 1980s that would be so indebted to his musical legacy.”

Bowie’s old friend Lou Reed is the subject of Lou Reed: The King of New York (Farrar, Straus and Giroux), Will Hermes’ remarkable biography of the Velvet Underground and solo titan. Hermes’ account of Reed’s final days is especially touching. “Reed and [Laurie] Anderson stayed up all night that Saturday, talking and doing breath work,” Hermes writes. “When daybreak came, he asked to be helped to the porch. ‘Take me into the light,’ Reed said — his final words, spoken on a Sunday morning.”

Finally, we have a trio of books about the Beatles, whose “final” single, “Now and Then,” was a qualified smash. The paperback edition of Paul McCartney’s The Lyrics: 1956 to the Present (Liveright) combines 2022’s two hardcover volumes into one weighty edition. This is a startlingly candid collection, featuring McCartney’s memories and some frank admissions. His discussion of John-and-Yoko diss track “Too Many People,” for example, features frank reflections on Lennon’s still-shocking “How Do You Sleep?”: “A lot of hurt went down during that period in the 1970s — them [the other Beatles] feeling hurt, me feeling hurt—but John being John, he was the one who would write a hurtful song. That was his bag.” In George Harrison: The Reluctant Beatle (Scribner), author Philip Norman follows up his biographies of the Beatles, Lennon, and McCartney with a much-needed overview of Harrison’s life and career. The standout sections are the post-Beatles days, specifically the controversies surrounding the coupling of Harrison’s wife, Patti, with his friend Eric Clapton; his troubled 1974 American tour; and his career as a film producer. Lastly, Living the Beatles Legend: The Untold Story of Mal Evans (Dey St.) by Kenneth Womack is the first full-length biography of the Beatles’ roadie and friend. As every Beatles fan knows, big Mal’s life ended tragically, but his love of the Fab Four was never diminished. “He had been right there with them—shoulder to shoulder, in the thick of everything,” Womack explains. Living the Beatles Legend is a tremendously important addition to the canon of Beatles texts.

Novels in brief

Our October 2023 column went long on noteworthy recent novels, but there are a few others that just missed the cut. Most notable are the final two releases from the late Cormac McCarthy, The Passenger and Stella Maris (Vintage International). It is hard to rank these two connected stories with McCarthy’s many gems. In time, though, both should be seen as fitting conclusions. (Stella Maris is, to me, the most satisfying of the two.)

Another major 2023 release, O Caledonia (Scribner), was actually written and first published in 1991. But as Hamnet author Maggie O’Farrell explains in her loving introduction, this novel by Elspeth Barker was long out of print. “The news that the novel was going back into print and into bookshops has been met by those in the know with unadulterated glee,” O’Farell writes. Start reading O Caledonia, with its description of the corpse of “sixteen-year-old Janet,” and you’ll be hooked just like O’Farrell was many years ago.

An October piece in the New Yorker by Ruth Franklin titled “How Queer is Frankenstein?” explored three novels that “reimagine Mary Shelley’s life and loves and her most famous creation.” The piece introduced me to Anne Eekhout’s Mary and the Birth of Frankenstein (Harper Via), an exceptional and passionate story that imagines an affair between Shelley and another woman. Queen Hereafter (Harper Perennial) by Isabelle Schuler is another bold reimagining, this time of Shakespeare’s Macbeth. (It is subtitled “A Novel of Lady Macbeth.”) And Hester (St. Martin’s Griffin) by Laurie Lico Albanese is one more novel that reimagines a classic tale—in this case, The Scarlet Letter. Hester concerns a fictional affair between a young seamstress and Scarlet author Nathanial Hawthorne.

Also worth checking out is The Star and the Strange Moon (Redhook) by Constance Sayers, a mystery with a unique connection to cinema; Fast Charlie (Titan Books) by Victor Gischler, a firecracker of a crime novel recently made into a film starring Pierce Brosnan and the late James Caan; and The Fury (Celadon Books) by Alex Michaelides, author of The Silent Patient and The Maidens. The latter is another novel for movie lovers, about a murder on a Greek island involving a reclusive film star.

And while it’s not a “novel,” American Demon: Eliot Ness and the Hunt for America’s Jack the Ripper (Minotaur Books) is historical nonfiction that reads like a detective thriller. Author Daniel Stashower brings the story of Cleveland’s “Mad Butcher” to vivid life. At one point, David Fincher was rumored to be adapting an acclaimed graphic novel version of this story, Torso, for the screen. American Demon would undoubtedly make for a harrowing film, too.