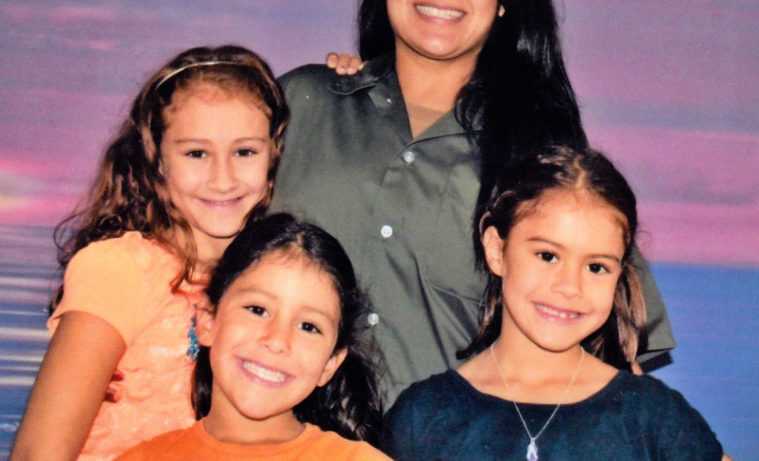

A powerful DIY film cobbled together from testimonials, iPhone videos, and home movies, Rudy Valdez’s personal documentary The Sentence explores the personal toll of mandatory minimum drug sentences on a family. Cindy, the one who pays the highest price, was not a mastermind behind a drug empire, she was simply in the wrong place at the wrong time. Six years after the death of her drug-dealing boyfriend, a happily married mother of three who has turned her life around is charged and arrested by the US Marshals and sent to federal prison for a 15-year sentence imposed by a judge who lacks the latitude to see the injustice.

The family, including Uncle Rudy and Cindy’s mind mannered handyman husband Adam, are left to raise three incredible daughters who grow up with a virtual mother. As Cindy is moved for undisclosed reasons from federal facility to federal facility, it becomes harder and harder to have the girls see her in person. Cindy tells her story to Rudy mostly over the phone as he struggles to make sense of what their next steps are both legally and as a family.

The Sentence is a powerful film full of rich, raw emotions as all parties explore their vulnerabilities. The film, it seems, is a coping mechanism for director Valdez, a decent man who has set out to prove through first-hand evidence just how evil these potentially well-intended drug laws are. No legislation is perfect, but mandatory minimum sentence laws destroy families and communities – there is no reason Cindy, who poses no risk to society, should have to raise her daughters remotely over the phone. Her incarceration also forces her husband, Adam to rethink the situation. Although he knew this was a possibility up front he’s now not living the life he expected to live.

A largely homemade affair, The Sentence interviews experts that were not related to Cindy’s case who discuss the law’s “girlfriend problem” – that is anyone having knowledge of crime could be considered a conspirator by simply not going to the police. There is a possible light at the end of the tunnel through a process that could almost be considered a lottery, although the film (like its filmmaker) isn’t interested in legal arguments as much as emotional arguments against the law. He admits several years into the journey she is in fact guilty and willing to admit it, but that the sentence does not fit her crime.

It is Valdez’s good fortune that the film is as effective as it is. Whereas an outsider might have chosen to rely only partly on home videos and impromptu iPhone interviews with his nieces, Valdez fully commits to a film told from inside the Valdez family. Credit must be given to editor Viridian Lieberman who provides enough editorial distance to help director-cinematographer-subject Rudy Valdez bring us into the story effectively without slipping into a larger political discussion.

The Sentence played at the Montclair Film Festival.