Despite Graham Nash’s words at the conclusion of Robin Lutz’s documentary M.C. Escher: Journey to Infinity stating that the world is destined to reappreciate the artist’s work, the fact that it’s taken three years for the film to become available in the United States seemingly proves the opposite. As the pop culture footage during the end credits reveals, however, it might just be that Nash was underestimating how important Escher’s art already was. From Labyrinth to Inception and tattoos to YouTube make-up tutorials, the Dutchman’s optical illusions and tessellations have been captivating and inspiring future generations for a century now. Just because his prints aren’t hanging next to Picassos doesn’t mean they’re any less ubiquitous or awe-inspiring. Like all great graphic design, their conceptual ingenuity transcends aesthetic categorization.

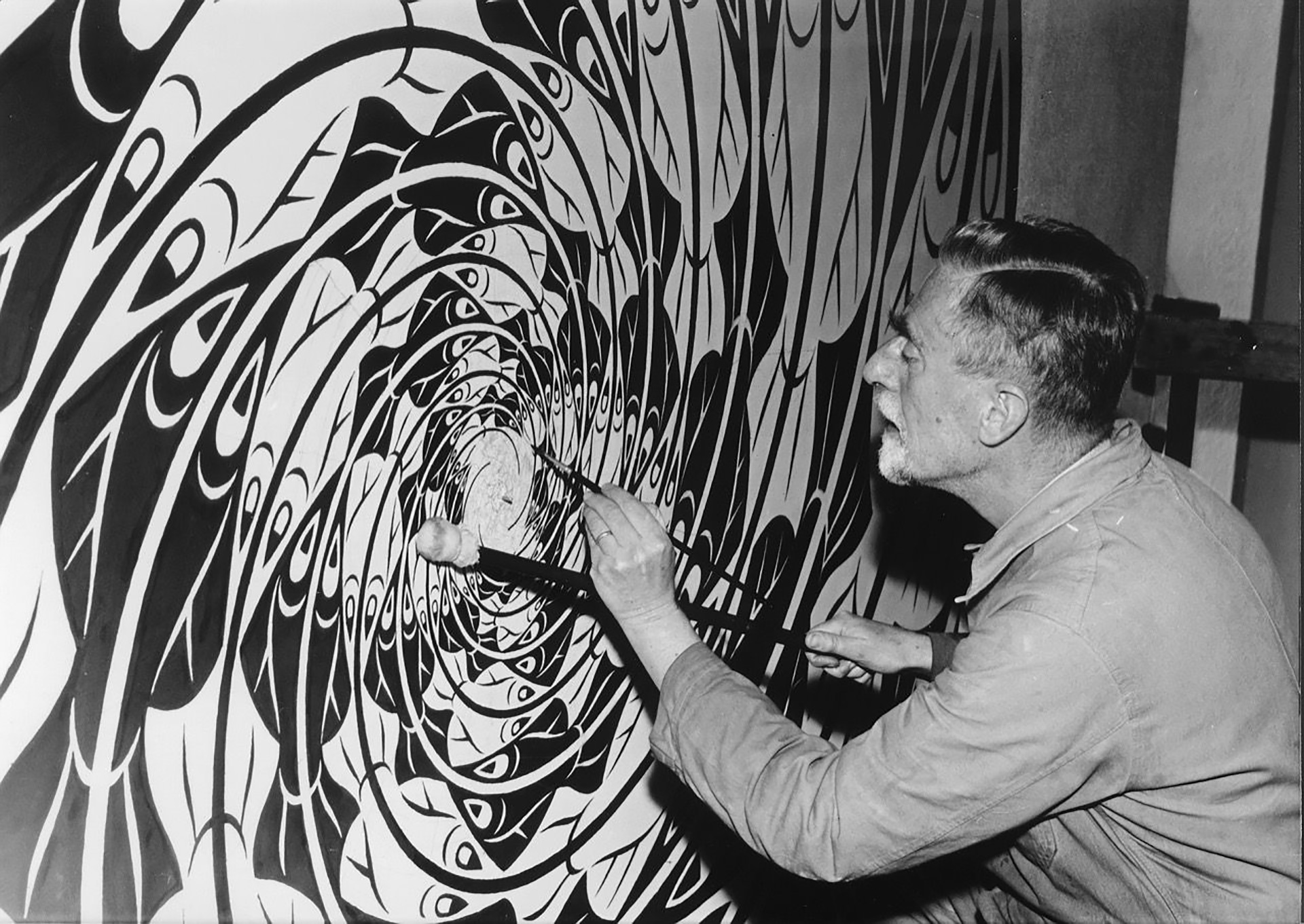

Which isn’t to say they don’t belong in galleries next to post-modern contemporaries or woodcut prints that came centuries before him. I could be biased considering my teenage bedroom’s walls were adorned by Hand with Reflecting Sphere, Drawing Hands, and Relativity rather than concert and/or movie posters, but the ways in which his complexly simple black and white drawings coax you inside them to get lost amidst their fluctuating positive and negative space cannot be undersold. And as Lutz’s film (co-written by Marijnke de Jong) portrays, that famous work only scratches the surface of his ambitions, evolution, and process. Between the chaos of rising fascism in Europe and a trip to the Alhambra palace in Spain, Escher’s commercial artist found himself reaching back in order to leap forward.

This is where Journey to Infinity proves itself to be a crucial biographical document even if it’s an imperfect film. I’m not sure that non-fans of Escher will be able to keep their attention spans up for 80-minutes of Stephen Fry reading from the artist’s own words (via letters, lectures, etc.) while the camera mostly dissolves on-location scenes into old photographs before they in turn dissolve into sketches and prints. It’s staid filmmaking with little sense of energy save the garishly bright and blinking colorizations Escher rightly denigrates in his confusion as to why hippies had begun to appreciate mathematically precise lithographs that were (in his mind) the antithesis of their free-wheeling spirits. Lutz has composed a university lecture in its own right: educationally pragmatic and historically enlightening.

That which might bore others, however, is exactly what appealed to me because there’s nothing better than digging into an artist’s aesthetic progression. Much like when Piet Mondrian (another Dutchman and evidence I obviously have a stylistic type) became the topic during college so we could push past his famous De Stijl paintings and recognize his proficiency in photo-real landscapes meant the former was a choice, viewing Escher’s observational drawings pre-Alhambra and the subsequent metamorphosis of his tessellations (sometimes merging both worlds together) is invaluable. The same goes for gazing upon the grid patterns he would ultimately build off of to manifest the likes of Encounter and Day and Night. We’re watching as Escher solidifies his voice while hearing the thought-process that went into its creation.

He’s a pretty entertaining character too. The way he talks about his craft and how it should be classified is as much due to modesty as it is a desire to control the conversation surrounding his art. Hearing from his sons George and Jan helps to elaborate on both this fact and the uncertain political circumstances that sent the family to Rome and back again before settling down to draw images from within rather than external depictions of their travels. And anecdotes like Escher going to his former teacher’s home (after he was taken by the Nazis) to save whatever work he could and ensure the legacy of his biggest influence wasn’t lost provide layers with more universal appeal than his ruminations on the art itself ever could.

Having those bits included amongst the rest gives us a more well-rounded image of the man behind the metal orbs so the film isn’t solely about the work. Whether it’s enough to keep you invested will depend on your appreciation of the latter, though, since the “journey” in the title is very clearly about what’s on the page rather than the life of the man leaning over it. “Infinity” deals with the endgame of Escher’s methodical themes as he moves from static representations to oscillating figures along a mobius strip (himself and wife Jetta Umiker included via Rind and Bond of Union—pieces that obviously inspired Kevin Tong’s recent Mulholland Drive) to circular “limits” that literally go on forever when rendered three-dimensionally. Escher’s oeuvre literally seeks formal perfection.

M.C. Escher: Journey to Infinity opens select virtual cinemas on February 5.