There is an inherent seriousness about Nicolas Winding Refn that is at first a bit startling, especially after sitting down for interviews with the affable and charming likes of Christina Hendricks and Albert Brooks. Refn, with his Puma track jacket zipped to the collar and hands wrapped around a once-full mug of coffee, is a serious thinker. He expects the same from his interviewers.

Refn delved deep into the process of making Drive, describing its curious inception thanks to Harrison Ford and REO Speedwagon, the inherent movie logic within his film, and the machinations of what drives the Driver. Interestingly enough, all of my critiques and comments about the film in my review are answered. Go figure.

The following is a transcript of a roundtable discussion with myself and three other journalists and Mr. Refn. Our questions are in bold, his answers follow.

The Film Stage: So where did you get the motivation to make this film? How did you become interested in it?

Nicolas Winding Refn: Ryan [Gosling] wanted to make a movie with me and I found an emotion that we could make a movie on.

When I talked to Ryan, he said that the 80’s music played a real big part in connecting it all together for you guys.

Well it’s because when he was driving me home from our first meeting, REO Speedwagon’s “I Can’t Fight This Feeling Anymore” was on the radio and I was really into that song when I was younger and so I turned it up really loud and [started to] sing to it which is really obnoxious to do when you’ve [just] met somebody for the first time in a car. We were going to Santa Monica to my hotel and then I was really out of it because I was really stoned at the same time because I actually had the flu, so Harrison Ford had gotten me these anti-flu drugs that made me, you know, took the fever down, but made me high as a kite. And when you’re like that as a guy you get all confused, and then I started to cry, and I missed my wife, my kids, everything and I also saw this image of a man driving a car by night and I turned to Ryan, I said, “we got it. We’re gonna make a movie about a man who drives around in a car at night, listening to pop music, because that’s his emotional relief. Because that’s the experience I just had at that exact moment. And he goes, “cool. Let’s do it.”

Were you listening to any particular songs during filming to motivate yourself?

Were you listening to any particular songs during filming to motivate yourself?

Oh, absolutely. When I make a movie I always try to figure out what kind of music it would be, because I don’t do drugs anymore, I would use the music to give me ideas cause I’m a fetish filmmaker. I make films based on what I want to see. So Kraftwerk and a lot of Brian Eno would be repeating itself in my iPod that I’d be listening to every day. Even while they were doing their scenes I would listen to music at the same time. And then I would continue to use that as we were editing cause we were cutting the movie at my house in LA. I found these songs with my editor Mat Newman who edits all of my movies who’s really into electronic music, much more than I am. And he would come with all of these suggestions. I took what I liked and then I had Cliff Martinez emulate the sound of the songs for the score. I wanted this kind of feminine, European, Eurovision sound. Complete opposite of the male masculinity of the car world and the stunt world so those two combinations would be the extremes of both ends. You combine that, you get some kind of energy that’s emotionable.

The lack of dialogue is almost shocking–

–For an American (smiles).

Did that happen in the script phase or once you had this strong, ensemble cast? Did you had Ryan, and then you pretty much started cutting the dialogue?

Yeah…and then…I cut most of it in our script, Hossein [Amini] and I. So basically when I handed in the shooting script before we started shooting it was 81 pages. By the time I was done shooting it was probably 60 pages, because I just kept taking out dialogue and dialogue and dialogue. Also because Ryan had a really good perspective. He said, “it would be really interesting if the driver doesn’t talk unless he’s asked something specific.” The driver is not a man who talks without having anything to say so the question has to be very specific for him to answer it. That made him silent as well. Ryan and I are very telekinetic. We think the same thoughts, and we’re like the same body.

For me, the strongest emotional scene was with Carey Mulligan, in that one stare-down. You got the entire scene by just their looks.

Falling in love is all about what you feel, not what you hear or say.

It came across very well, as I’m sure you’re well aware.

Good. (laughs) Thank you.

Was it an intention from the beginning to have this main character in a thriller/action film be so inward?

I don’t see him as inwards because there’s nothing for him to be inwards about. He’s a normal human being that does normal things but his DNA for some reason just does not belong in our world. He’s like a man of mythological proportions. You know, he’s fine with his solitude and he’s fine without his solitude. He falls in love with the purity of love and he realizes that it’s in danger he will protect it at any costs. It’s higher than normal love because it’s about what’s between him and his god in a way.

Yet there’s such contrast between the violent, sporadic scenes and the rest of his kind of, quiet….

Well it’s like a Grimm’s Fairy Tale, which was very inspiring to me when I was structuring the film in that it starts off very champagne-like and it ends very violently but very fair. The wrong ones are punished and the innocent prevails, you know? And that’s who he is, that when he is needed, he will become our human being, and when she needs a hero, he will become her hero.

One thing I was wondering while I was watching it is why isn’t it enough for him to be a stunt driver in a Hollywood film? Why does he have to go into the criminal life that he does? What is it in him that does it?

It’s something so deeper in him that it’s existentialistic (smiles). It doesn’t have an answer because he doesn’t get anything out of doing his criminal activities. But [he’s] like a movie mythology character.

And it’s not like he’s driven by greed or anything like that.

No. All that I eliminated because I wanted him to be more like a monolith, in a way. More enigmatic. Because that meant that there was always a different side to his behavior than you would expect. What he does in the beginning never repeats itself until he has to do it to protect her, and that’s where everything goes wrong. So he’s probably done this before and will continue to do it because it’s part of his DNA. Why he does it is the exact reason why he does it. You understand what I’m saying?

He has that kind of Searchers mentality.

Because he will never find the answer, that’s why he does it.

Yeah. That he has that void in him that he has to kind of fill in some way.

It’s not even a “fill,” it’s who he is. And again, he’s part of movie mythology. [James] Sallis‘ book is very interesting because it’s about movie mythology, and about people living in movie mythology and people having difficulties not relating to reality but seeing reality in a different way.

Was it more difficult than to put that sort of monolith within all these different people who were pretty fleshed out, more regular? Was that the dynamic you were going for?

Yes, beacuse then he becomes what they need. He represents their inner mirrors. When she needs a human being, he’s a human being. When she needs a hero, he’s a hero. When Bernie [Albert Brooks] needs his nemesis, he becomes his nemesis. When Shannon needs his dream of buying a car with the greatest driver he becomes the greatest driver. He’s everything to everyone.

So he’s just sort of a moving foil for everyone.

Yeah.

Loraine [Carey Mulligan] asks Driver what he does and he says, “I drive.” He defines himself through driving. What do you think driving is for him?

Well he says to her, she says, “what do you do?” he says, “drive” and she goes, “what, limosuines?” And he goes, “no, for the movies.” So he drives in the world of illusions. And in the end of the film, he tells Bernie Rose that he’s a scorpion, because he’s been transformed into this superhero, The Scorpion. So in the end [spoiler], it’s like seeing a scorpion kill silently and deadly. But it’s inevitable.

Especially since they’re in a parking lot. It’s not a closed environment.

It’s out in public.

I found it interesting that the opening scene is predicated on escaping the police. And then as the story gets further along it gets more insular. The outside world doesn’t matter so much anymore.

It’s almost like he becomes his own movie, with its own movie logic.

You mentioned how you both sat there and figured out what movie you wanted to make, did you then sort of seek out a project to fill that role or did you find a script along those lines?

Well, Universal had been trying to make this movie for, like, six years, and had not done so, and decided not to do it. So it was basically a project that had never gotten off the ground. It was very different because Universal wanted to do a very different kind of movie and I wanted to do something completely different from what they wanted to do. And no studio would finanace it so I had to go to the world of independent financing, which meant that, of course, I was back to square one: low budget and no time, which I’m used to, which was comfortable, because then I knew how to play it out. And I know I could do it and be able to make the movie I wanted to make.

How were you able to get this wonderful ensemble cast? Everyone is just phenomenal.

Well I was very fortunate. But then again I was in Los Angeles and they’re all there. That’s the thing. Everybody wants to work in their hometown and [people] rarely [do], so just the idea of working locally gave me access to a lot of talent both in front of and behind camera for very little money. And I was fortunate that Christina [Hendricks] came by. I had never seen Mad Men, but I was asked by her agent if I would meet with her and I was like, “yeah, sure. Anybody’s open.” I was casting porn stars at that point for that role and then she came. We talked, and I really liked her, and I just automatically knew that she would work. Same thing with Ron Perlman. [He] called me, wanted to be in the film. Met Carey Mulligan, same thing. Albert was [a] similar situation. He was interested, I knew, from the beginning and I called him and we talked and I met at my house and I clearly saw this man was a volcano of emotion (laughs) and that if he didn’t kill somebody soon he was going to do it for real so let’s do it in a movie, get it out.

Is that what made you realize you could tap into his darker side ?

Yeah. There was a lot of particular movement [he made] that made me think, “Hm. Well, when he’s going to kill, he’s going to kill you with a knife. And you’re going to be almost so surprised when it comes.” So I came up with this whole knife obsession of his.

Was there something in particular that he did that made you start to think that?

Well he was just so, like…fetish about certain things. I very quickly read into that the first time we met.

Like obsessive compulsive?

Yeah, particular [things]: how he would sit, how he would move.

Coiled spring.

Well like I said, a director doesn’t have to be an expert on anything. But he has to know a little bit about everything. So that’s what you do. One of your [jobs] is to observe.

This depends on situations, but psychologists analyze that because we watch violence in movies, we don’t actually try to cause crimes. What are your thoughts about including violence in your movies?

Well I don’t believe that violence in art form makes people violent. I think that it can show people how to be violent and if it helps to trigger something in them that’s already there, that’s of course when it gets difficult. I also believe that any kind of art form can be a release of tensions and frustrations the same way sexual pleasure can do. It’s very linked together. So it’s great therapy (smiles).

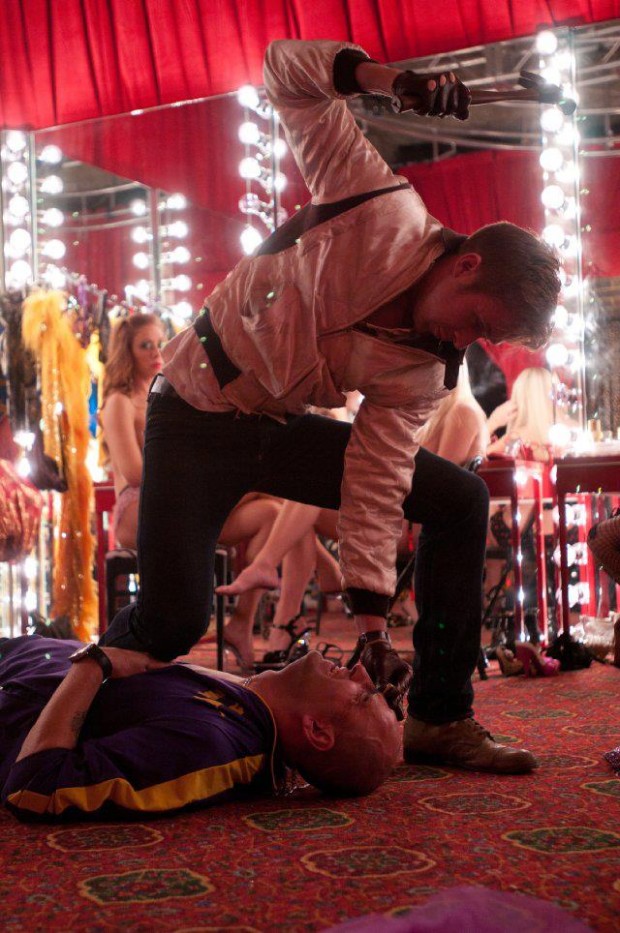

With the violence, was it always that punctuated? When you talked earlier, it seems like a series of extremes put together.

Yeah, it had to have extreme notions, and it was always trying to figure out what could be another great way of killing anybody. Cause I knew I never wanted the driver to have a gun. He had to be like a super hero. Basically the movie is about a man who transforms himself into a superhero. That was the fun part: how could he kill this guy? Huh! I should do this, I should do that. The idea of drowning [a character] I really liked, how he goes out there and just drowns him.

And did that structure of having a lot of quiet stretches, did that evolve or did that come from the beginning?

No, I always like silence. It’s my favorite sound. I believe silence is the greatest sound of all and a lot of people fear it because silence reminds you…it can remind you that you’re just a spectator. But at the same time, it could touch you deeply beacuse silence forces you to feel because you can’t hear it.

You pause the action, you get to sense the characters more.

Or even just the acting itself, people just looking at each other. It can be very powerful if it’s done right. It can also be terrible if it’s done wrong. And what’s interesting is that you can’t hide anything. It’s the purest of purest, so there’s no way to throw you attention span into another direction. You see is what you have.

I think Trouffaut said it was very hard to make an anti-war film because any time you show that sort of action on screen that it would seem so attractive. And in the same right, showing a car chase could seem really thrilling, that you really want to be in that role vicariously. When you pull away from it, it seems that a lot of that is lost. Is that something that was on your mind, of not wanting to idealize, or kind of make that role attractive through the adrenaline of the chase?

I never thought of it like that. I do believe you can make a war movie that makes you a pacifist. If you’ve seen Elem Klimov‘s Come and See you automatically want to go tattoo peace signs [on] your body, throw roses everywhere. Have any of you seen that movie? It’s one of the greatest films ever made. It’s from 1985, a war movie about the Germans trying to invade Russia and it’s a masterpiece.

How limiting was it, then, with an adaptation? Or were you able to just take the bits that you wanted and go out from there?

Oh, absolutely. I mean, again, I’m not the greatest filmmaker. There are lots of better filmmakers than me. But I’m the best filmmaker and the kind of films that I make. So there was nothing else to do but to choose what I liked and then go with it. And I always knew in the end that Ryan Gosling would protect me. If it ever came to be an issue with my financiers or with people around me. And it didn’t. And then I realized that they were there to help me as well, even though I was paranoid as hell. Here I was coming to Hollywood for the first time. You only hear the horror stories and I was just really, really lucky, and I had good people around me who maybe not understood what I was doing, but decided to protect it. Because Ryan and I were so in synch that it was all about everybody else to almost cocoon me and Ryan in to doing what we wanted to do because there were no other options on the table.

And are you two going to work together again at any point?

Well we’re doing two movies back-to-back now. We’re doing Only God Forgives around Christmas and then we’re set to do the remake of Logan’s Run after.

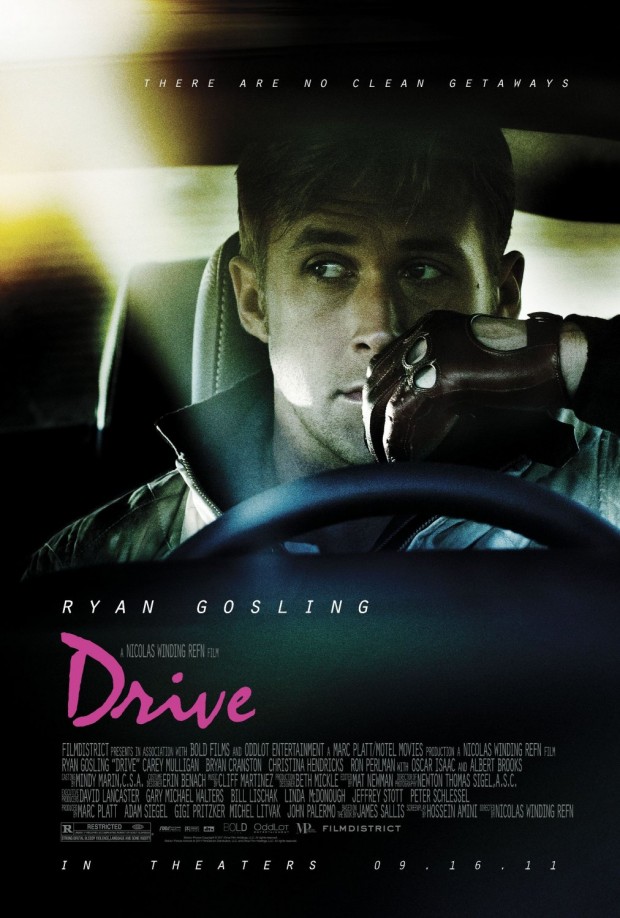

Drive is in theaters nationwide today, September 16th.