A small, harmless frog peacefully existing by the water is the first image presented in Feels Good Man. What follows from that serene moment––a nod to the source of innocent inspiration for Pepe the Frog––is a clear-eyed, disturbing look at how the playful creation was perverted and carried through a malevolent maelstrom of digital discourse in the darkest corners of the internet. Arthur Jones’ documentary stays sharply focused on the specific path in which Pepe the Frog eventually became classified as a hate symbol by the Anti-Defamation League, but he also paints a larger, more terrifying picture of how an anonymous population wields the power to shift political change from their keyboards and the juvenile motivation in which their flimsy ideology is founded upon.

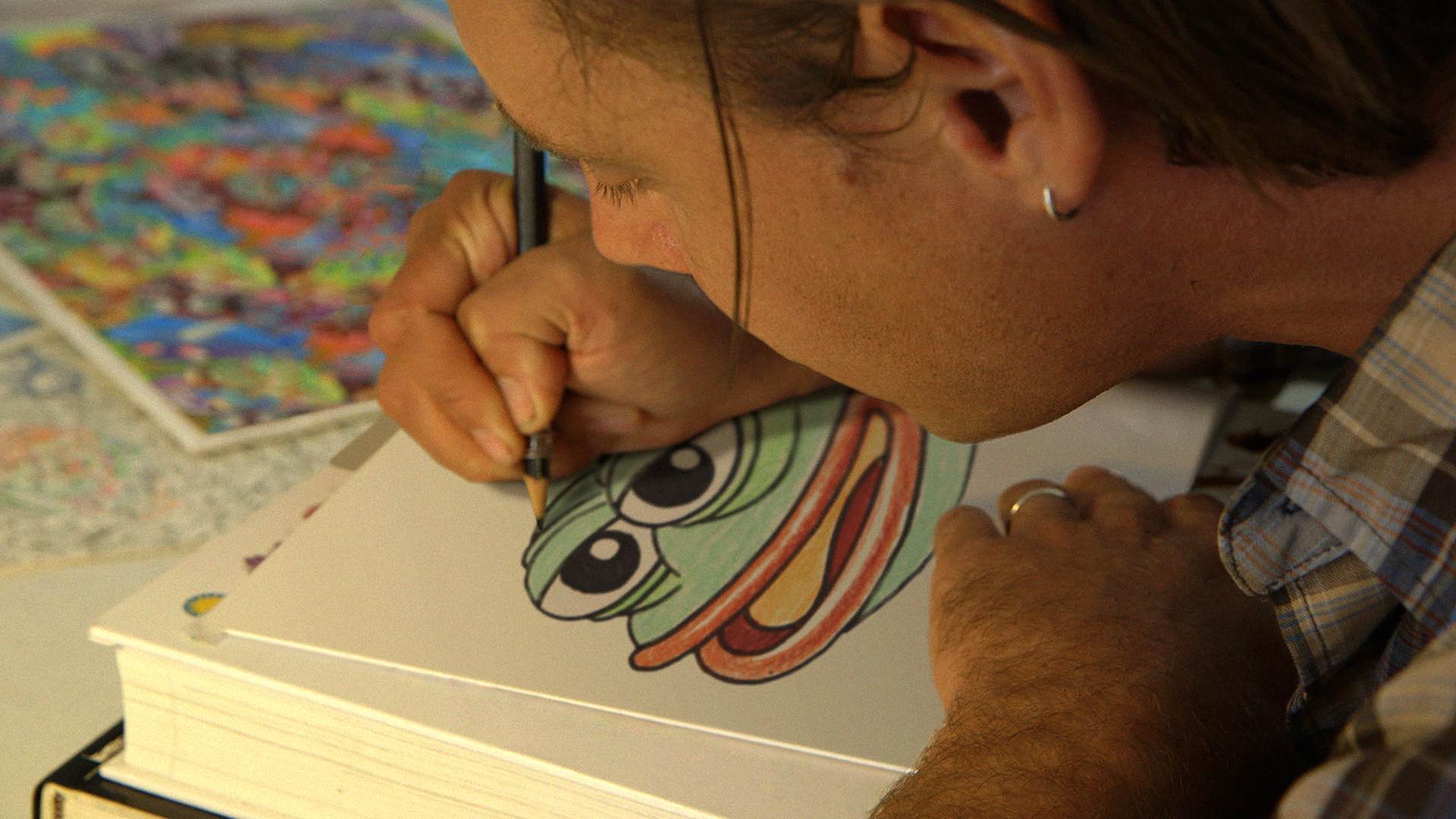

Pepe the Frog, created in 2005 by Matt Furie (who appears throughout the documentary, and may be the most chill person imaginable), began as a “little brother” side character in Boy’s Club, a cult comic hit that reveled in silly, but lighthearted sensibilities. (After all, the name Pepe was inspired by “pee-pee.”) The first seeds planted across the internet of this meme-to-be were not of Pepe himself, but rather the phrase in the comic from which the documentary takes its name. “Feels good man” began circulating as a response from those who just lifted weights, snapping pics of their muscles to share, both on forums and the more relaxed vibe of MySpace, a bygone place where “it felt like you were looking in somebody’s locker,” Furie says. If one was on the internet at this time, they certainly came across how the phrase was co-opted with memes of dogs, Obama, and, yes, John Goodman. It was after this point where renditions of Pepe became more connected with the phrase, quickly leading to it becoming synonymous with 4chan, the massively popular imageboard in which 90% of users post anonymously and are encouraged to one-up each other in grotesqueness.

With Pepe as his guiding force, Jones charts this previous decade-plus (d)evolution and proliferation of the internet and specifically the ways in which a single image can become debauched far beyond the control of its creator––in Pepe’s case, a ubiquitous emblem for a torrent of white nationalism and hatred. For those who only recognize Pepe in his most infamously-known form, the director expertly and impressively takes a step-by-step look at how such an abominable process could occur. We see Pepe used by the likes of Nicki Minaj and Katy Perry, which fueled the ire of 4chan users as the meme became popularized in culture. The outrage over something being normalized that they thought was exclusively their own led to more disturbing versions and uses of Pepe, ultimately resulting in it being co-opted by Donald Trump and his legion of supporters as an icon of xenophobia.

Whereas many documentaries, and certainly narrative features, about the ever-evolving digital age can feel as if they take a bird’s eye view from the perspective of an out-of-touch adult looking into a world they barely recognize, Feels Good Man sketches a frighteningly recognizable timeline and environment for those whose formative years were intertwined with mid-to-late 2000s internet culture. Digging deeper than a surface-level view of memes such as “Sad Keanu,” Jones interviews members of 4chan about the appeal of the site to the millions of visitors and how it was a place where those still living in their parent’s basement felt “alone together” and owned their loserdom. As these feelings of isolation and arrested development became a collective foundation for conversation amongst NEETs and incels, it can lead to the kind of dialogue that gives way to actions far more harmful then internet trolling. In a section that perhaps deserves its own documentary to dissect, Jones explores the idea of a “Beta Uprising,” which led to deplorable acts of violence such as those carried out by Elliot Roger, who killed six people in retribution for being rejected by women and being envious of sexually active men.

Feels Good Man skillfully details the pathway the internet provided, and those using it anonymously and potentially obliviously, that led to how a single image coded in guarded irony was the regrettably precise tool to spew hate at a large swath of people. With Pepe’s comically-drawn face, not to mention “smug Pepe,” which resembles the personification of Trump himself, it could be put next to the most insulting, horrendous imagery and messages, but those posting (and the millions viewing) could make the excuse that it’s acerbic satire and brush off any harm it may inflict. For its creator, who didn’t know what a meme was when his creation became one, he sees its all as garbage. “We celebrate garbage and produce garbage. America is a garbage world.” Perhaps naively, Furie says of how Pepe has been co-opted, “It sucks, but nothing’s forever.” While there’s a tinge of hope the symbol of Pepe is already shifting, as it is being used in Hong Kong protests as an icon of freedom and hope, Feels Good Man shows that with an estimated 160 million postings of Pepe per year online, it’s incredibly difficult for a creator to take back control of their work. It’s a depressing, disturbing journey to witness, but an essential one to see the machinations of evil that pervade and influence our daily life on the internet and beyond.

Feels Good Man arrives on Friday, September 4.