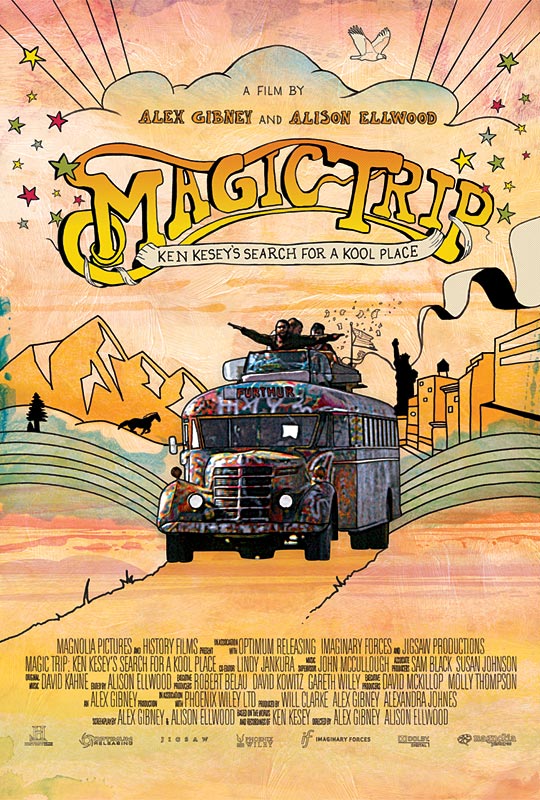

The most crucial–and difficult–thing about creating a good interview is flow. The best discussions come from conversations, the natural way that things topics move from one in to the other. Which is what makes a round-table interview so fascinating, such as the one that I and two other journalistic strangers conducted with Alison Ellwood, co-director and editor of Magic Trip: Ken Kesey’s Search for a Kool Place.

Originally, we were to be joined by the film’s other director, Alex Gibney, as well, but he had to leave before we got a chance to interview him. So it goes. Unfortunately, one of the other interviewers in the room was completely prepared to ask Mr. Gibney questions about greed, money, and evil corporations: a summation of his life work that bares little moral resemblance to the film at hand. Have fun guessing which questions are his in the ensuing transcript!

How big a project was it? When we think about it, it’s not ancient history, but it’s long ago enough and film is fragile enough it had to be a project just to put this all together.

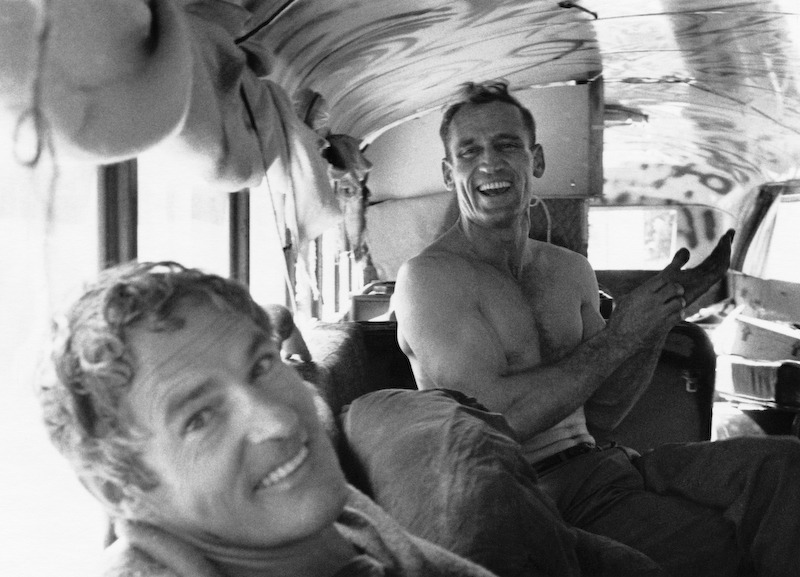

Yeah, it was a pretty big restoration project. And if you consider that this film has been in production since 1964 it’s a long wait to get it finished. The footage was about fifty hours of 16mm footage. They had shot reversal film, which is a positive image which, unfortunately, allowed them to project it without duplicating it. And they did, they projected it at the acid test parties. They then tried to cut and make a film themselves out of it so they started editing the material and did that for quite a number of years, so the footage got pretty severely damaged. So, basically, it was found six years ago in the barn at [Ken] Kesey‘s house in Oregon and we shipped it down to UCLA where they began a restoration process where they repaired it, cleaned it, tried to make sense of what was what and where things were and it took a couple years to do that. And then there was the 150 hours of audio recording that they did as well. They didn’t really know how to use film equipment, they weren’t film makers, so they didn’t know you had to do (clap) a clap so you could sync the sound with the picture. We had one clap in fifty hours of material. We did manage to find a few scenes synced, including some of the footage of [Neil] Cassady driving up the New Jersey Turnpike, which was great. But for the most part we had to be creative in layering sound to make it fit.

How did you create the raw atmosphere as if we’re experiencing the trip. Could you talk about it from the storytelling and editing aspects?

When I look at that footage, I found it immediately pulled me into it. I felt like I could smell the bus fumes, I feel like I’m there. The footage is raw. They’re not trained camera people filming this material, so it’s very jerky, it’s very short takes often. They did manage to expose a lot of it really beautifully, so that’s good. We just wanted it to be a very experiential, immersive experience for people to watch, and that’s how I felt looking at it, so it’s sort of the angle that I approached the material from, it was to try and keep it like that. We didn’t do traditional interviews. It would take you out of that moment. It was always trying to keep you in the moment.

With that in mind, how hard was it to try and cull a narrative out of that. Was most of it just watching their trip on their trips, or was it trying to find exactly where the beginning, middle, and end of that story would be?

It’s both. There is a chronology to the trip. There’s the trip from west to east then back and then what happened afterwards. So we had that as a starting place. I think one of the early things that helped me, anyway, definite how to tell the story versus laying out the footage was in the Yellowstone Park scene, where he sees a sign that says, “Beware of the Bear” and Ken [Kesey] says, “it used to mean, ‘be aware of the bear’ and now it means ‘be afraid of the bear.'” That moment for me was very significant because I realized that all the scenes, at least most of them, had to have that layer of depth to them. So we started trying to approach scenes like that and so people would say different things. Often Ken talking not just about what you’re looking at, but about some other concept. Like being an explorer, or that kind of thing. It took off and on for six years, so it took a long time (laughs).

It’s an interesting portrait of the country at that time. Just as a snapshot of what they were observing because, I think, through the media, we all think of the 60’s that we were already psychedelic. But when you look at it, as it says in the film, you would have thought we were in the 50’s.

It’s an interesting portrait of the country at that time. Just as a snapshot of what they were observing because, I think, through the media, we all think of the 60’s that we were already psychedelic. But when you look at it, as it says in the film, you would have thought we were in the 50’s.

Yeah, it’s very much Mad Men era there. Absolutely one, if not both feet, still in the 50’s. The 60’s as we think of them probably only lasted a few years before it was the 70’s. I mean it really came in much later. And these guys, this is an origin story. They were the spark–or one of the sparks, they weren’t the only one–but they were certainly one of the big sparks that got the thing going.

What would you want to do if you could go back to the 60’s?

If they would have had me, I certainly would have been on the bus (laughter). What an adventure, right?

As a woman, what do you think of the women on the ride?

Eh, you know…. For me, I wouldn’t have hesitated for a second. I would have wanted to be there, so I don’t think of it as anything unusual that they were there. Probably given the time, it probably was unusual for these unmarried women to be jumping on this bus with all these guys and going off on this crazy road trip but, y’know, more power to them. They’re great.

At what point did you decide this was going to be a story about Ken Kesey as well as a story about the experience that he went on? It feels almost bookended by this biography as this trip that he went on in the middle is the most influential part of his life, almost.

Right. Well, the project began by finding this footage that was this trip and journey, so we knew that was the guts of our story. But we had to set it up and we had to contextualize it. Ken was the impetus for the trip and he was this amazing writer. So we wanted to set up the time and who Ken was. It’s important to understand that he was this successful writer who basically threw, after two incredible novels, basically threw it away because this bus became the new thing he wanted to do. So it is bookended with Kesey, and it is his story, but it’s just part of his story, too.

How much help was his son to you?

They were great in allowing us to work with the material and do what we were able to do. They didn’t have constraints on us, which was great and they’re all very happy with the film, so that’s good.

It’s fun to see the bus as it is today, though [slowly becoming one with nature]. I mean, kind of sad but kind of interesting. I was reading the notes and there’s some kind of project to get it–

It has been pulled out of the swamp, subsequently. That footage was actually shot a while ago by a friend of mine. So it’s been pulled out of the swamp, it’s in the barn. But there is a second bus that actually Ken helped to build many years ago that actually went on tour in England about fifteen, sixteen years ago. And Zane [Kesey, Ken’s aforementioned son] gets that bus out and drives it around Oregon up in Eugene.

I got on the bus…(lightly giggles).

How are people reacting today to it? I mean younger people, people who were the age of the people who were on the bus, what do they think of all this?

Different people, obviously, different reactions. A lot of kids are excited because the 60’s are so mythologized for them that they’ve said to me, “well, we could never go back and experience it but this film gets us as close to actually feeling like what it might have been like.” So that’s great to hear. And you know older people, it’s [like] acid flashbacks. Good memories, bad memories, whatever. So far, very positive, so that’s good.

What was the truth that you found in seeing all of the footage and creating this film?

It’s an interesting question. I’ve said this before but I feel we’re in a time now that’s, I think, very similar to the time that they came out of. Very fearful. And there’s a lot of powers that be in charge of things that we feel helpless about. And Ken felt that. His idea was, “get out of the bunker, have some fun, you don’t have to conform to what they say.” And I feel that there’s a lot of similarity to our time now and I hope people can walk away from this film with an interest in exploration of what else is out there.

Talking about the looking back prospect of this, during the voice-over it seemed like some of the [Merry band of] Pranksters were watching this footage for the firs time, trying to reconcile what was happening. Was that part of the overall message?

Well those interviews with the Pranksters were conducted about twelve years after the trip and recorded. And they literally were watching the footage and talking about it, so that’s where that came from, so they’re absolutely recalling it. Earlier on we decided we wouldn’t go and seek out getting on-camera interviews with them. We would only use that, just so you would always stay in the footage.

Were you ever able to contact them afterwards? I know that sussing out the footage I’m sure they were helpful but is there anything else that influenced you in making this film currently?

No, no.

It was interesting, having read Tom Wolfe’s account, to have a different take on all this. Because that was pretty much considered the definitive [story] even though, as you said [in the movie], he wasn’t there. So do you think that would get a response from people, having a different take than his?

It was interesting, having read Tom Wolfe’s account, to have a different take on all this. Because that was pretty much considered the definitive [story] even though, as you said [in the movie], he wasn’t there. So do you think that would get a response from people, having a different take than his?

I hope so! Definitely. I can’t imagine it won’t. This is the real deal. The footage is right in front of you, you know?

How did you get a hold of Ken Kesey’s [original] acid test administered by the government?

Believe it or not, that was just found in a white box, audio box, in the barn at Kesey’s. It just said, “V.A. Hospital, 1960,” or whatever the year is, I can’t remember. And we got it back to New York and had it transferred and we start listening to it and we go, “oh my god, this can’t be what this is?” And sure enough, it was the real thing. We’re going to have an extended bit of it in the DVD extras because it goes on for about forty-five minutes. He stops the tape recorder several times but you hear Nurse Ratched [from One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest]. That is so clearly Nurse Ratched talking, you know?

What do you think is your responsibility as a film maker?

To tell stories. To look behind the curtain and to show what’s there because often we’re afraid of what’s behind the curtain because we think it’s, you know, the wizard, but it turns out to be a little guy who has no power whatsoever. And as often as you can pull back the curtain to try and reveal or show something exciting and new and different.

Was there much of a difference as a documentarian editor as a documentarian director?

Frankly, an editor of documentaries does a huge amount of the story and the structure and really is essentially directing also. And this was all archival footage so it was an editing job, it’s what it was.

A monsterous editing job.

(laughter) Yes.

What were your thoughts on putting music to all this?

We wanted to put music…I mean everybody thinks, again, jumping forward into the 60’s, that wasn’t what they were listening to, it didn’t exist then. The Beatles were just coming out then. Rock and roll was just beginning. What they were listening to was jazz and R&B and some early rock, for sure. So we have “Love Potion No. 9” by the Coasters in there, we have the Isley Brothers singing “Shout!” The attempt was to absolutely make it what they were listening to. Even the [Grateful] Dead music at the end is very early. It’s from the very first album they put it. They were actually called, initially, “The Warlocks,” so even that we wanted to be true to the time.

How did they pay for this trip?

Ken paid for it. I don’t know, I think materialism is connected to money in this. It had taken over a lot of possibility for spiritual quest. We’re also ingrained to believe that we have to have this device and this device and this, and this, and this. And it’s all such a scramble to get to that place. Someone asked if a trip like this could take place now. How could you do it? With all the kids and their gear and their phones and this and that, it would be different if you geared up a bus and painted a bus. It would be different.

With the films that you and Alex have worked on, it seems as if there is a lot of a small group of people that have some sort of hold over a larger amount of folks. In that way, much of the other examples have a negative connotation. When you think of this film, with the Pranksters, does that have a positive or negative effect over their generation?

Both. Certainly they were inspirational and, y’know, it’s not as though they went through life without damage to themselves or to others around them. Taking drugs is a dangerous thing to do if you’re not careful and smart about it. Really, honestly, both. I don’t think it’s one or the other. I don’t think anything is ever purely one or the other.

I think of poor “Stark Naked” being left behind.

I think of poor “Stark Naked” being left behind.

Yeah. Then she rejoined them later and went out of her mind again, later. So, you know, who knows? She couldn’t handle it. I mean Cassady died an there is a lot of sadness, and there’s a darkside to this story. People might think this is a nostalgic look back and it’s not our intent. It’s not supposed to be a nostalgic look back at all. There’s warts here, too.

Of all the footage–all the tons of hours of footage–how much of it was simply unusable in general? How much of it do you still want to be a part of this film?

When UCLA would call us and they would say, “well this is what it says, should we bother transferring it?” And sometimes it was a call. We had a certain amount of money; we couldn’t [restore] every single bit of it. The trip back is the most disappointing not to be in the film because we actually really enjoy that footage. It’s also much cleaner than the rest of it because they weren’t as interested in the trip back so they didn’t hack it up. They projected it a few times but they never tried to include it in a film so there was all this relatively pristine footage without scratches and burn marks and cuts and all that. And it was very beautiful and had a different pace, because Cassady driving to the East Coast was like a drum beat, bum-buh-bum-buh-bum. Driving three days on speed, for instance.

Coming back, it was much, much mellower. And they did things like stop at these farms and you see Kesey out in the field with this thing of grain in his mouth and a cowboy hat and this combine driving [by] which is, of course, a great thing to be driving by him given the meaning of the word for him. Y’know, going to a country fair, a trip they took to Tijuana, Mexico to a bull fight. Those were the things that were really sad for us to lose. And they’ll be in the DVD extras so people will get to see them. But it was just beautiful moments that [were at] a totally different tempo. And when you get to that point, you need to be wrapping the film up, not going off on a whole other new tangent.

How much extra footage will be on the DVD?

There’s not gonna be a lot but you’ll get a sense of a bunch of different scenes. There will probably be snippets from ten different scenes.

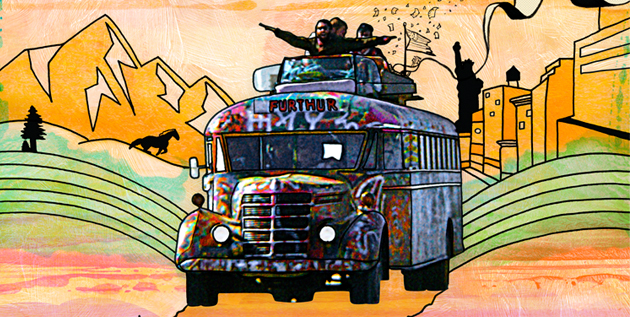

There are great bits of animation, especially in the opening and in that Kesey acid trip. Just brilliant. As a director, do you sort of give that off and let the animators sort of do their work?

No, we worked together, all of us worked on it. Imaginary Forces did the animation. They did a spectacular job. We had the audio tape of Ken’s trip at the V.A. hospital and we obviously had no footage of it so I cut together a three-and-a-half minute sequence. It was one of the very first things we did, was we got that, working with them and they did storyboards. We wanted everything to start from something seeming real, like you see the Woolensak tape recorder, you see the bed, the glass of water. And as it progresses it gets stranger and strangers and more abstract and more abstract until the end where it’s all bats flying and this and that. But it was always the idea that it would come from the [recording] and come out and get stranger.

There are four places where we do it. The beginning was just to play around with introducing this cast of characters, these players, as the case may be. And then in Wikieup [Arizona] when Gretchen is in the pond, tripping. Those photographs are so beautiful, but just to give that extra little layer because she’s communing with algae, y’know? And you wouldn’t get that if you just saw the pictures but if you animate it a little bit and give it a little bit of extra something. We didn’t want to go over the top with any of this. Again, that psychodelia wasn’t even invented at that point. It was coming soon but it wasn’t there yet.

Probably had to think of this whole psychodelia thing, saying, “we can’t get ahead of ourselves.” I’m guessing that was sort of a watch word, because people want it right away, it’s what they know, it’s what they’ve seen.

I mean, we have little hints of it early on. Like the little wheels that go psychadelic because otherwise it was just a black-and-white opening and we thought we would turn people off right away. We gotta get a little weird with this so people know what’s coming.

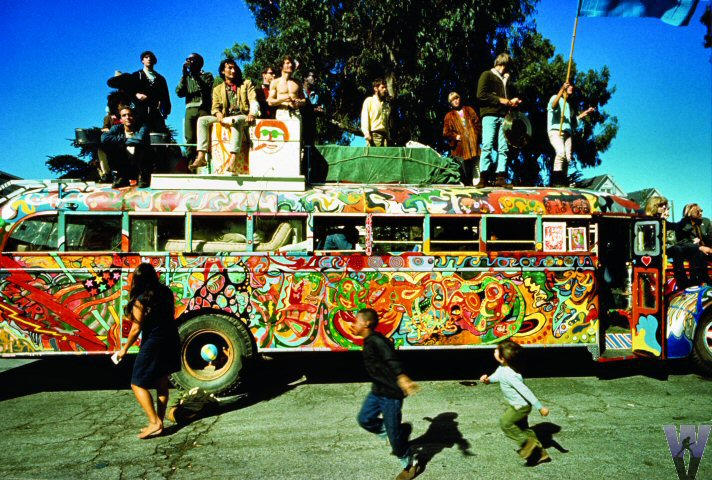

Really, the bus was the most psychedelic part.

Oh absolutely. When that thing busts out, you go “whoa!” It’s like color bursts out of a black-and-white world, which was very much what it was.

And even that changed. There was no continuity for that bus. Every reel there was a different bus.

Yeah.

For me, only knowing bits about this, it was a very educational experience. To see tye-dye shirts being created, for instance. A lot of what you know of the 60’s comes out of this trip, almost. From your experience, what was something that you learned about this experience that you weren’t aware of ahead of time?

I guess what surprised me the most was their innocence, their patriotism. I would have thought they would be a little bit more jaded, a little bit more of what came later. I was very young when this trip happened, only three. There is a statement that Ken makes that I just love, “I’m just basically an average, all-American, clean cut guy who happens to be an acid head.” I’m not sure that I would have connected those two things being possible prior to this.

I remember the World’s Fair opening. My parents were looking for a car and the Super Ball had just been invented, we had a Super ball, and that was our bit of technology tying us in to the World’s Fair. And I live in Queens, so I see that sphere fairly often, and it’s weird to look at it now in this context.

I remember the World’s Fair opening. My parents were looking for a car and the Super Ball had just been invented, we had a Super ball, and that was our bit of technology tying us in to the World’s Fair. And I live in Queens, so I see that sphere fairly often, and it’s weird to look at it now in this context.

When we first started working on this film I went out there and started filming, going in the pavilion, which is closed off and barricaded. They were going to knock it down so I said, “we gotta get out there.” And I somehow got locked…there’s a theatre built right up against it and I went out the theatre door and got locked inside and I couldn’t get back in. It’s all just decay and the map of the world is all cracked and grass is growing up in between it. It’s just amazing. It’s beautiful, actually.

People do bad things in the name of job or whatever. They don’t want to think about morals. Could you talk about human psychology and how you reach to Magic Trip through that?

I think Alex and I are both interested in the line that divides morality and immorality. And it’s a very thin line, and a very easy line to get closer and closer to and the closer you get to it, I think the less you see it. Good people do cross over that line and those are very interesting characters, I think, because they’re tragically flawed, basically, and they make for interesting stories. Because we all have that capability and it’s a little bit of rubbernecking. You turn your head to look at a car wreck. We all have that sort of desire to look but most of us don’t. Thankfully most of us don’t cross over.

I don’t know how that relates to this film. I really don’t, honestly. I think that there were certainly some negative things that happened as a result of the explosion of drugs that Kesey was a huge player in making happen in San Francisco, certainly. But it certainly wasn’t an immoral intent to cause any harm whatsoever. He was a light seeker, a truth seeker, and thought that this would help people open their eyes and see new things and open consciousness and better mankind. He believed the tests he was doing with the government were to benefit sick people, people with schizophrenia. He had no idea he was being used by the CIA and others were being used by the CIA to test tools of interrogation. So I think that’s the closest that element comes in to this story.

Of the hundred fifty hours or so of audio, how much of that is just Cassady talking at the bus?

Probably only a few hours of it. There’s probably a little bit more of it but then other things happen. They would stop the recorder or they would suddenly decide to switch speeds that they were recording at [she demonstrates fast and slow speed; I won’t attempt to textualize it]. That was a restoration job, too. Don Fleming had to go through and speed-shift everything.

Part of that problem, [the Pranksters] didn’t know the Nagra [sound recorder] could switch speeds and secondly it was often being run off the bus generator which was run off the bus’s stick shift so you get all that warble happening. There were bits and pieces. There was a lot of Ken just mumbling. Sometimes he would–oh, this is what kills me–he would take an audio recording that had obviously been done in the field and you could hear bits of it still and he’d record over it. Just mumbling, watching footage and stuff, and you could hear him recording over something that was original. (laughs) Oh god. We could use what we had, so…

We’re lucky they used a Nagra.

Yeah, yeah. There were some great shots of Sandy, the “sound man” with the cables coming out of his mouth and around his neck.

What interested me is that the impetus of the trip was not just the road but to use this new camera technology to go on that and it’s interesting that what they were making has become a trip that is a document of them going on the trip. They went out to film an experience and became the experience. Was that interesting for you as a director to sort of finish their journey?

Yeah, it’s interesting, it’s challenging, it’s scary. I was really scared about how they were going to act, cause what if they didn’t like it? But they were all really happy, so that’s great. And the journey is the destination and came from this, which is great. And that’s a good thing for people to walk away from. Because how you get there, the road, is what counts.

And when the destination ends up being the World’s Fair, who wants to get there? (laughter)

It is not a cool place.

Magic Trip opens today in limited release and is available through Video On Demand. A listing of the scheduled release locations can be found here.