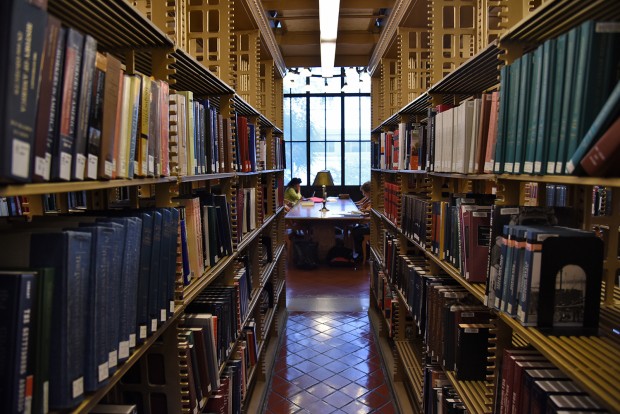

The Stephen A. Schwarzman Building, also known as the “Main Branch” of the New York Public Library, is located at 42nd Street and 5th Avenue, next to Bryant Park. Almost 150 years ago that was the setting of the Murray Hill Reservoir, which supplied drinking water for most of the city through the end of the 19th century. It’s perhaps no coincide that the NYPL’s headquarters are located there, since they have taken on the duty of supplying the city with knowledge and culture, elements which are as essential to New Yorkers as water. The iconic building is at the center of Frederick Wiseman’s Ex Libris, an enthralling documentary that chronicles the work the NYPL continues to do since its inception in 1911.

Wiseman’s enlightening, often quite moving film, explores the NYPL’s reach beyond 42nd Street, through its almost 90 branches, which provide courses, talks and, of course, books to the boroughs of the Bronx and Staten Island. In the film Wiseman showcases several aspects of the NYPL including its archives and the arduous work of preservation, master classes in which intellectuals challenge New Yorkers to see the world around them in a different way, and practical courses like job interview prep, and technology lessons. The film arrives at a time when knowledge is under constant attack at the hands of an administration which seems keen on dumbing down Americans in order to maintain the status quo. Wiseman’s generous film then might be also unwillingly be his most political, as it’s impossible to watch Ex Libris and not feel the urgent desire to act.

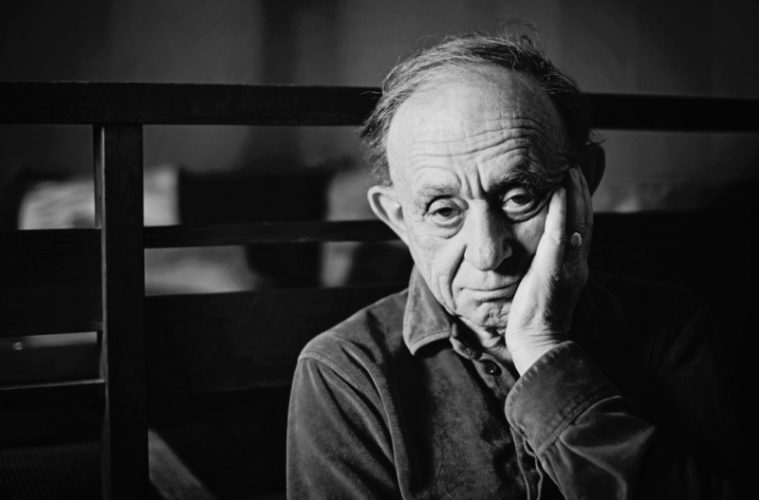

I sat down with the idiosyncratic filmmaker to discuss the reasons why he wanted to tell the story of the NYPL, how his films are influenced by literature, and how he’s developed an eye for discovering larger than life characters.

Can you recall the earliest experience you had at the public library?

My mother used to take me to the public library by our house in Boston, when I was six or seven years old. I went to the library a lot as a kid. I’m not sure I remember the first one. My mother taught me how to read a lot.

I grew up in a country without libraries, so I was in such awe when I first realized the richness of the experience waiting for me at the NYPL. When did you realize a library was more than just a collection of books as the film shows?

I don’t know when I first felt it, but when I was in school and started writing papers in the 6th or 7th grade — I’m not sure if I knew how to use words like “richness” back then and I probably took it for granted — but I knew that the library was a treasure trove of things I wanted to read.

How much about making Ex Libris had to do with you wanting to know how the NYPL worked?

Well, I’m not aware if I thought that. I really had no experience with libraries since the time I left college or law school which was a very long time ago. I hadn’t thought much about libraries since. I started off with the thought that maybe a library would be a good addition to the institutional series that I’ve been doing. I had no real knowledge of what libraries were currently doing. The president of the NYPL was good enough to give me permission to make this. I spent maybe half a day working on the main branch on 42nd street and another day visiting various branches in Staten Island, the Bronx and Manhattan, and then I started shooting. The shooting of the film is the research, which is a perfect example of the method I use when I make my films. During the shooting I accumulate a lot of material with no particular idea of how I’m going to use it, and no knowledge of what the point of view or the structure of the film will be. It’s only in the editing that it all gets figured out, so the final film is a response of being at the place and then spending a year thinking about it.

The structure of the film made me think of the solar system with the main branch serving as the sun around which all the smaller planets revolve. How did you settle on this in the editing?

There are more locations in this movie than in any other film I’ve done. I think the movie takes place in 13 or 14 different sites, and in the editing it was a problem to figure out the links and how to suggest the geographical differences in the location of the libraries. As you see in the film I did it with transitional shots, suggesting we’re no longer in midtown Manhattan but in the Bronx. Those transitional shots also serve as pauses between mayor sequences. Each movie presents a different series of challenges, because the locations are different and the kinds of transitions you need as a result are also different.

I loved how you also crafted a story about the importance of immigrants in creating the fabric of America. You show scenes in which Asian immigrants go to the library to get help with their computers for instance. Did the aftermath of the election have anything to do with your wanting to highlight this?

I finished the editing two days after the election so the election didn’t guide me, but I think Trump did me a great service because everything he represents is the opposite of what the NYPL represents. The library represents democracy, openness, inclusiveness, diversity, educational opportunity regardless of race, ethnicity, or social class. I don’t need to outline what Trump represents. The consequences of Trump’s election underline the importance of the library, which in a sense, not deliberately, represent the opposite of what he is. The library is perhaps the most democratic institution. It’s open to everyone.

Watching the film I kept thinking “I hope the president never watches this movie because then he’ll try to shut down the NYPL.”

[Laughs] I don’t think he’d have the patience to watch three hours and 17 minutes.

He’d realize the government is funding his nemesis.

There is an effort on the part of the right to dumb down American education. The budget for the humanities is often the first thing that gets cut. Sometimes it’s necessary, but sometimes it’s a political motive, a wish to create a society of technocrats, people who don’t know how to think clearly about social issues. There are well-financed groups on the far right, the Koch brothers being one of many, who are trying to do that.

By the end of the film you’ve showed how despite the majesty of the main branch, it’s not an intimidating place at all.

I hope people aren’t intimidated. In my experience it’s a place that welcomes everybody and people help with your questions. In one sequence in the film we have one woman who is trying to find the town her father and grandfather came from. You can call the NYPL and have questions like that answered on the phone. It’s an institution with very deep roots in the community, which is impressive in any age, but especially now. The only condition is you can’t disrupt, but other than that you don’t need an ID, you can borrow a book with a driver’s license, it’s very easy to take books out, and everybody can use the facilities. That’s one of the many reasons it represents the idea of democracy at its best.

In the film we hear a discussion about how NYPL employees should deal with the homeless people who come into the building to sleep. I was quite moved by the way in which the executives spoke about the issue with such humanity. We don’t find out what they decided to do in the end, but it made me wonder if you go back to find out what happened to unfinished storylines in your films?

No, once I finish a movie I’ve exhausted the subject from my point of view. I rarely watch the movie again because it’s more interesting for me to go on to something new. By the time a movie’s finished I can recite all the dialogue by heart; maybe I watch them 10 or 15 years later. There’s movies I haven’t looked at for over 30 years — not for lack of interest, but because I have them in my head.

Can you talk about the experience of turning Titicut Follies into a ballet?

I worked very closely with the choreographer. I spent about six-to-seven weeks in rehearsal. I’m not a choreographer but I offered my comments on the dramatic aspects all the time. I enjoyed the process, because I’d made a couple of ballet movies and I go to the ballet. I was struck by how many of the ballets that I saw were either re-doings of 19th century ballets or 20th century ballets that echoed the 19th century ones. I didn’t see many dances that dealt with contemporary lives other than ballets about relationships. As important and interesting as relationships can be, there are other things going on in the world. I thought a prison for the criminally insane was an extreme aspect of contemporary life that hadn’t been touched on, and also the movements of psychotic people – their tics and obsessional behavior – might be transformed into dance. I wanted to see how all of that could be transformed into dance using classical ballet technique.

Did this make you want to make more ballet films?

No, I’ve had the privilege of making movies about two of the greatest dance companies in the world, the American Ballet Theatre and the Paris Opera Ballet. I wouldn’t turn down the opportunity to do another one, but it’s not in my plans.

Would you say that the structure of the NYPL remind you of any other of the institutions you’ve covered?

I hadn’t thought about that. Only in the sense that any institution of any size has a structure, but I think the NYPL, of all the movies I’ve done, is the most complex organizational structure because it’s so big. There’s the main branch and around 90 subsidiary branches of varying sizes — the NYPL at Lincoln Center is enormous, there’s a special library for the blind, in addition to all the other branches. The principal administrators who work out of 42nd street are supervising and devising strategies for such a wide range of activities. I was interested in suggesting that complexity.

You could’ve made a whole movie about the branch at Lincoln Center.

You could’ve made a whole movie about any of the branches!

With so many potential roads to take, how do you restrict yourself when trying to find the story you want to tell?

It was the challenge of the editing, to find a rhythm that would suggest the variety of activities taking place within the system as a whole and not concentrate on just one place, but also to suggest how it’s all planned from a central place and implemented in the branches. It’s a two-way collaboration. Obviously the branches are sort of the front. People running the branches know things the administrators don’t, but the administrators are the ones dealing with the whole picture and they encourage the people in the branches to participate and provide input that will help influence decisions that are made centrally.

I think that in this film, more than any other you’ve done, you’re expecting a direct reaction from people. After watching the movie I spent the rest of my afternoon working from the branch on 42nd street for instance.

Oh, that’s great! I don’t make the movies with that in mind, but I’m delighted to hear the movie had that effect on you. It’s a great place for learning and to hang out, everything is there. If you’re a curious person you can spend your whole life in that reading room.

I love the processes you show, like the preservation of huge images and the recording of audiobooks. Were there any processes you shot but simply couldn’t fit in the final cut?

Usually what ends up in the movie is naturally what I think are the best of the rushes. On the other hand, a place as vast at the NYPL you can’t cover everything. I don’t believe any of the movies I made are comprehensive in a sense of me covering all the bases. With the NYPL I only begin to suggest the complexity of the place.

I feel that by now you’ve made a movie for almost every kind of person in the world.

I’m glad to hear you say that but it was certainly never a formal goal. I’m interested in making movies about as many topics as I can. I like the idea that cumulatively I’ll have made movies about as many different aspects of contemporary life as I can during the time I’m alive and can work.

What are some topics you’ve never been able to cover but would love to?

The CIA, the White House, the FBI. But somehow I doubt I’ll get permission.

Your last few movies have mostly focused on the arts, which is beautiful in a twisted way, because especially right now you’re helping us remember that the arts are pillars of society.

Exactly.

Going back and thinking about National Gallery and Ex Libris, for example, do you feel more excited to be making these movies when the world really needs them?

It’s funny, I don’t think about it in those terms, but rather subjects that interest me and I’ve never covered before. I’ve repeated myself a little bit with dance movies and films on schools, but the movies aren’t made out of formal analysis but more what interests me at the time for many reasons. It also has to be a subject I can spend a year on, it’s a total immersion so it has to be something that really interests me.

You’re notoriously never in your movies, but you also must be in them.

A couple of times in the past as a joke I’ve been physically present in a shot.

Like Hitchcock. Would you feel comfortable giving any clues of how we can find your ideas in the films? I keep hearing the word “Wiseman-esque” and thought you could help me decipher what that means.

I have no idea what that means. One critic I know of, but won’t identify, uses that phrase, but to him that means movies about poor people in relation to the state. He doesn’t like the movies I make about cultural institutions because they’re not “Wiseman-esque,” but that shows a misunderstanding of what I’m trying to do. I think ballet is as Wiseman-esque as welfare because the technique is the same and it’s the same effort in trying to understand what’s going on in the place. Also, I hope one of the things that characterizes the work as a group of films is that it’s just as important to make movies about a group of people who are doing a good job and trying to do one, as it is to show people exploiting other people and taking advantage of them. For example in ’86 or ’87 I made a movie about an intensive care unit at Beth Israel Hospital in Boston and the nurses and doctors there are busting their asses to help people. Similarly when I made Hospital in 1968 the doctors and nurses would work 24-36 hours without resting because they wanted to help people, but there was a Marxist critic who wrote about the movie and said it didn’t show the doctors and nurses exploiting blacks and Hispanics. Clearly he’d never spent any time in an emergency room because it wasn’t the case. It was an argument from an ideological position. Similarly the people in the NYPL and the staff is really interested in helping people. That’s nice to see in any day and age but particularly nice to see now.

It’s so interesting that this critic would say that about your movies about art, because even in Ex Libris we see the differences between social classes and ethnicities. People get different things out of the NYPL according to their social status. We see white people attending lectures with big stars, while people of color come for help with job interviews and practical lessons.

One of the themes of the movie is the experience of blacks in America.

One of my favorite moments in any of your movies is the fashion show in High School.

[Laughs] When the teacher says her legs are too thick for the stuff. It’s funny and sad. It’s ridiculous too!

Sadly I’ve never watched Model, but I wondered if this sequence was on your mind when you shot it years later?

There’s no direct connection really. Model happened through a very funny sequence of events. I was sitting at my dentist’s office and the dentist is the only place where I’d read People magazine and they had an article about a modeling agency. I was 48 at the time and figured it was the right time in my life to make a movie about models, so I did.

And yet no movie about the dentist.

W.C. Fields has done that brilliantly.

Nowadays we often see people from nonfiction films and reality television become stars of sorts. Your films are filled with incredible people, how come none of them have really had a “breakthrough” in this sense?

The taxi prof in In Jackson Heights was great! That’s one of the funniest scenes in any of the movies. He’s a great teacher and has a great presence, but fortunately for him he didn’t become a reality TV star.

Going through the rushes how do you know when you’ve found this star?

I never think of it in those terms. I just respond to whether they are good sequences. The verbal and visual content have to be interesting, At Berkeley is more dependent on talk, Model is more dependent on pictures.

Are you interested in dividing your movies and making television series?

No. Sometimes I’ve been asked to break the movies up but they wouldn’t work. From my point of view they have very carefully thought out dramatic structures. If, for instance, I made Ex Libris into three movies it wouldn’t work. It would be a different movie because each time I’d have to start all over again and establish the characters, the place, the interrelationship with the themes would be impossible to explore. In addition, sometimes the films are long, but they’re long not out of any perverseness on my part but because the subjects are complicated. I have a greater obligation to the people who gave me permission to make the film and the people in the film, than I do to the needs of a theater or television chain. I’m grateful to public television because they always show my films as I made them without any interference for primetime.

Ex Libris more than any of your other films made me think of an epic novel like War and Peace…

I like your association.

I wondered if you felt your films had more in common with literature than any other artform.

My approach to making these movies is much more novelistic than it is journalistic, I still read much more than I go to the movies. I’m aware of influences, but I think I’m more influenced by the books I’ve read than the movies I’ve seen. Whatever form you work with, in an abstract sense you’re dealing with the same issues: characterization, the passage of time, metaphor, abstraction, etc. That’s the kind of thing I have in mind because the structure of the movies is very carefully worked out. For me the editing is much more like writing than anything else, I have to think about the way I introduce characters and what I say about them. For a movie to work it has to work in two ways: as a literal track and an abstract track. The real movie is created in the relationship between the literal and the abstract.

Why don’t you go to the movies more often?

After 10 hours in the editing room it’s hard. When I go to the movies I like seeing old, classic movies. Often when I go to the movies they’re terrible. Maybe I just pick the wrong ones?

Ex Libris is now in theaters.