In 2021 Joel Coen directed his first feature apart from his brother. Seven months after The Tragedy of Macbeth‘s premiere, it’s Ethan’s turn to fly solo. The projects couldn’t be more disparate. Where Joel went for a black-and-white expressionist Shakespearean drama led by Denzel Washington and Frances McDormand, Ethan settled on a minor music doc about rock ‘n’ roll legend Jerry Lee Lewis. And settle he did.

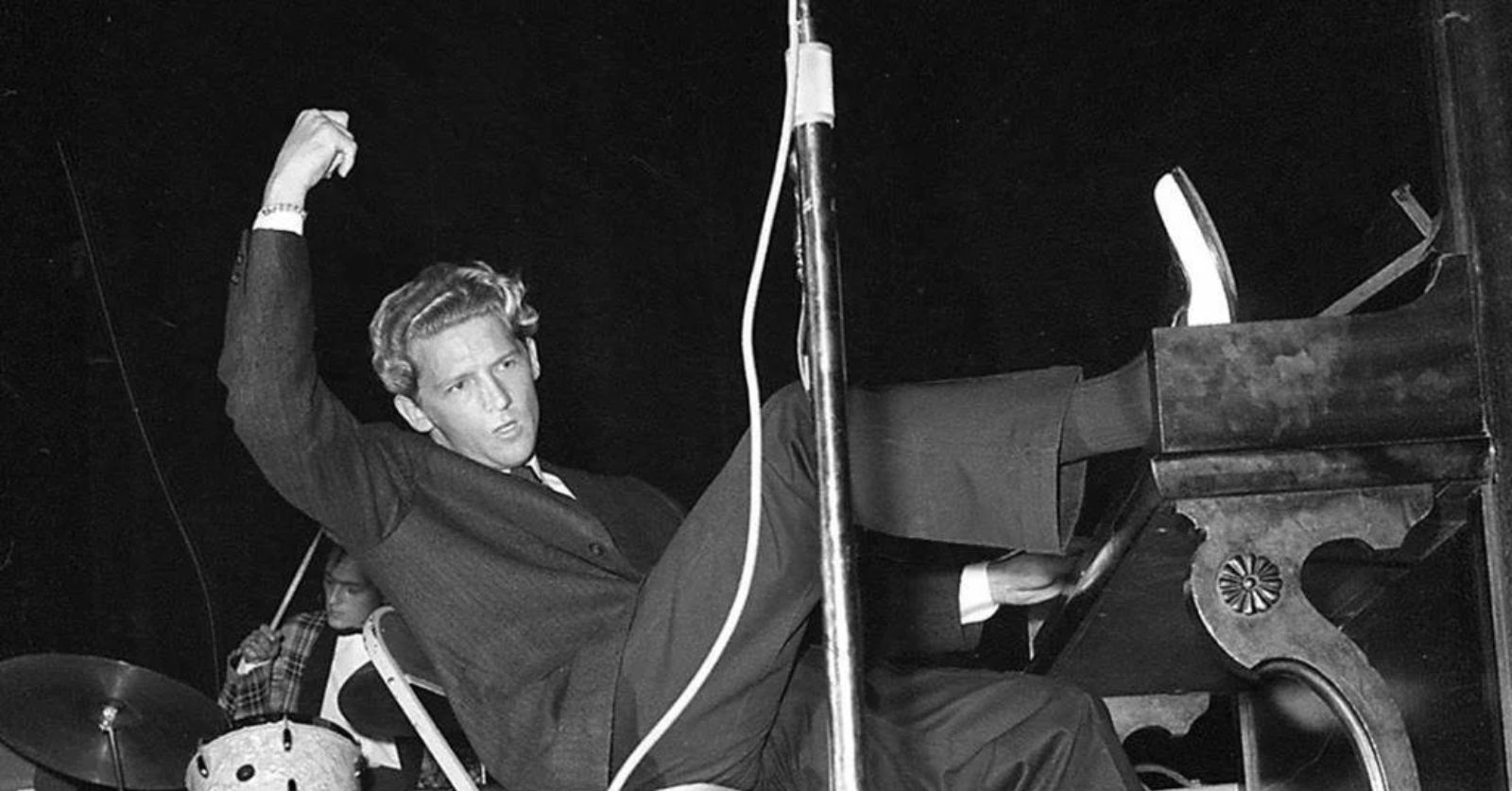

Jerry Lee Lewis: Trouble in Mind kicks off with two great videos of Jerry Lee Lewis that you can probably watch online right now. The first is an older Lewis playing a lovely country rendition of Ernest Tubb’s “Walking the Floor Over You”; the second is a young, prime Lewis blowing your mind with his April 1957 single “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On.” It’s a strong start, especially for those who haven’t seen him play. The man is a plain-and-simple musical luminary. He kicks back his chair or throws off his coat mid-piano solo without missing a beat and you immediately understand why he was a phenomenon: the immaculate piano work, golden voice, dynamic style, inebriating confidence, insane performance ethic, and Iggy Pop-level energy on stage. Throw all of that in a cocktail and you’ve got a lethal drink, a palpable charisma. But once the opening videos end, there’s not much to stick around for.

After “Whole Lotta Shakin’” we move to a series of interviews from different times in his life, then to a performance of “Great Balls of Fire,” some more interviews, some more performances, and, as it turns out, very little insight into Jerry Lee Lewis. Thirty minutes in—with all interesting ledes sufficiently buried or ignored, the charm of his husky southern drawl faded—you realize you’ve been conned into letting Coen take you on a YouTube train of his favorite Lewis performances and interviews. If you like Lewis’s sound, that’s fun for a short while. Then you realize he’s just playing the same songs on repeat and it starts to get annoying, as getting cornered at a party usually does.

Notwithstanding Coen as a music connoisseur himself, it’s baffling to have a luminary like T Bone Burnett (frequent collaborator since The Big Lebowski) as a producer and still have a project that manages to miss so much of the music. Replaying a handful of his most popular songs over and over, if anything, suggests the rest of them weren’t that great. However, they do rub it in by emphasizing the ungodly amount of songs he recorded. Otherwise Coen, Burnett, and company simply don’t address major aspects of his career.

They don’t spend any time on his discography, for one. Barring a few quotes about him recording “a zillion” songs, we don’t get so much as a mention of one of the 40 studio albums he recorded between 1958 and 2014. His volatile record-label trajectory from Sun Records to Smash Records back to Sun Records to Mercury Records goes wholly undiscussed, and that only covers up to 1979. They don’t interview artists, agents, friends, venue managers, or anyone who might offer a supporting perspective on the controversial figure or even recollect a good memory from working with him or seeing him play.

They don’t tell us whether he wrote and/or arranged some, most, or none of his own music, though it’s loosely implied that he was a pioneer in the arrangement category. We see him playing piano, his main instrument by a mile, 95% of the time, but the footage of one gut punch of a guitar lick compels one to ask what else he could play, what else did he do. Those things never come up. They don’t get into relationships with the other Sun Records icons—Elvis, Johnny Cash, Roy Orbison—or collaborations with other artists, of which he had many.

Outside the music, and perhaps most notably, Trouble in Mind doesn’t get into his personal life at all. Docs can’t be held responsible for answering on behalf of their subjects, much less their subjects’ sins, and a biography doc doesn’t necessitate covering someone’s life from birth to death. But you’d think a doc called Trouble in Mind might get into the “trouble” at least a little bit.

Instead it only briefly mentions his rampant alcoholism and skates past the marriage to his 13-year-old cousin with a tastelessly cute demeanor, focusing only on the fact that he hemorrhaged fans as a result and had to spend 12 long years on the road. After a couple of minutes the segment ends with clips of Lewis answering questions about the marriage in interviews. He quips about her actually being 12 on the day they married, saying assuredly that he always felt good about it and thought it was something he needed to do. Then we’re back to performance footage, fully moved on without a lick of research outside some newspaper headlines from the times to evidence the pop-cultural upheaval it doesn’t get into.

The film ends with the title card followed by a peculiar word crawl of fast facts we’ve already covered, and the interesting things we learned about him—like the fact that his parents mortgaged their home to buy him a piano, or the way he does funny raptor arms when he’s feeling it on the piano—don’t carry enough weight to overcome the sluggish supercut-esque pacing and, ultimately, lazy approach. At 73 minutes, Jerry Lee Lewis: Trouble in Mind ends up feeling awfully long.

Jerry Lee Lewis: Trouble in Mind premiered at the Cannes Film Festival.