Scott Cooper is comfortable in the mud. The American director routinely finds himself in the confines of the lowdown and dirty, in gritty landscapes with working-class characters overcoming their shortcomings and often turning to violence to solve their problems. While his previous two features Black Mass and Hostiles failed to find tension in their deliberately tedious pacing, Antlers strikes the balance between methodology, terror, and blue-collar dynamics.

Its prologue shows the grime that has become of a nameless Oregon town––sparse landscapes of the Pacific Northwest, grey air, oil rigs, polluted skies, and jobless Americans attempting to make a living after what once was a coal-mining town has all but descended into a town of the unemployed. Scott Haze plays Frank Weaver, a father of two who leaves one of his sons in the truck while he dives into a cave to make meth with his partner. Surrounded by medicine bags that act as defense totems, the pair get gouged out by an identifiable beast and the son (Sawyer Jones) soon follows.

The meandering, brooding tone that bogged down Cooper’s previous films works well on this genre canvas. From the effectively chilling, tone-setting prologue, the slow ease of his camera works to create actual tension from not knowing what may be around each corner. We soon are introduced to the classroom of Julia Meadows (Keri Russell), talking to her 12-year-olds about myths and storytelling. The obvious thematic pairing between protagonist and story lends an eye-roll even as it moves Antlers in the right direction. Julia is sister to the town sheriff Paul Medows (Jesse Plemons), and both have a history marred by trauma—an abusive dad is glimpsed in subtle flashbacks, random household items all the while sparking awful memories for the siblings. She’ll often glance over at vodka shooters that recall nightmarish memories or apologize to Plemons for leaving him with their father. Plemons is great as the steady, reluctant sheriff, recalling his work on the Fargo series.

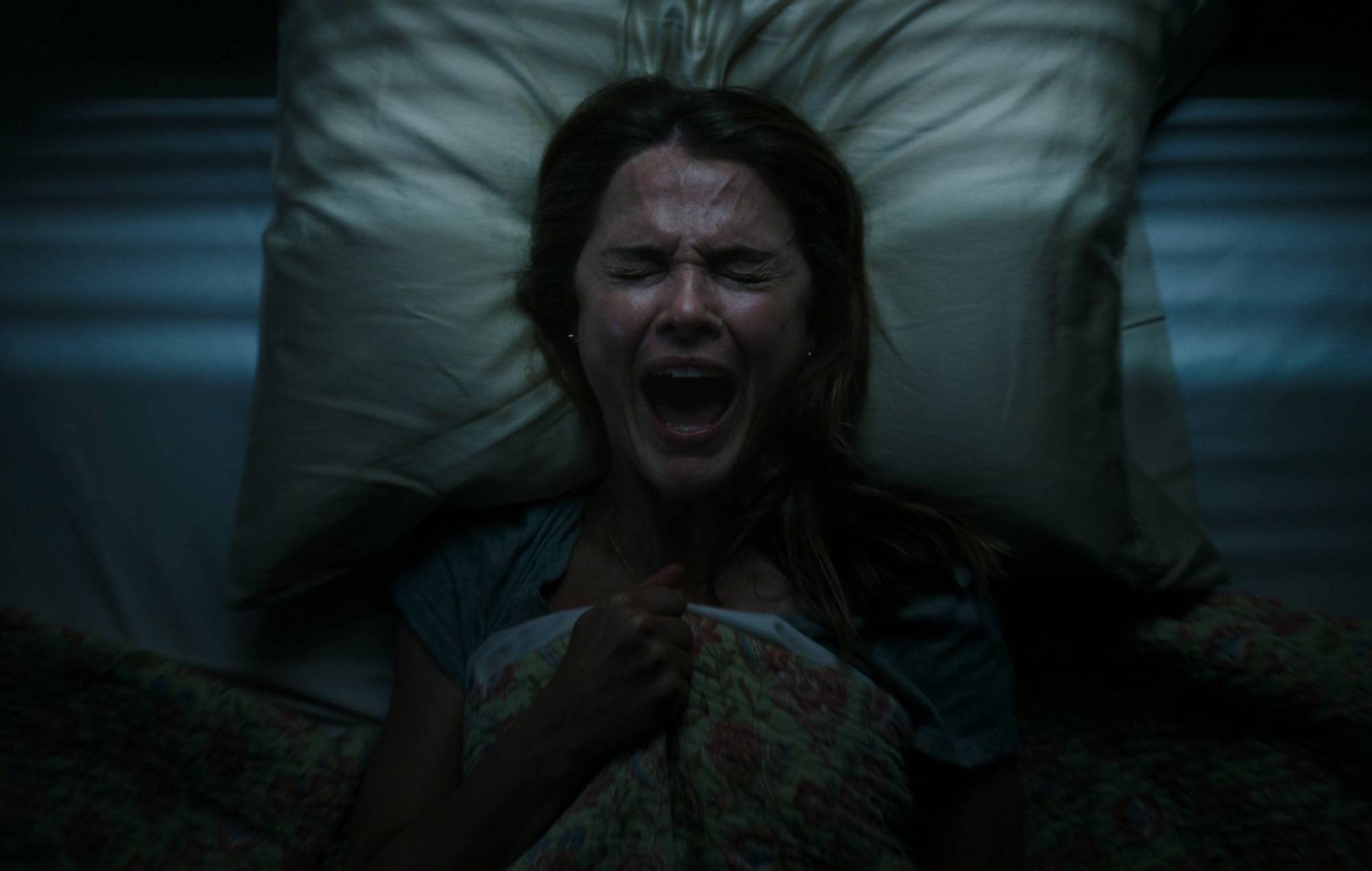

Russell also stands out as a wounded soul slowly putting herself back together, attempting to rescue the younger Lucas Weaver (Jeremy Thomas), whom she recognizes as requiring help—the scars of her family resonate in him. The first-time child actor excels as he burrows right into the darkness and depths of the abuse, quietly uncomfortable in his skin but also believable as someone strong enough to take care of his ailing household. Lucas has sketches of the beast hidden in his desk along with books about ancient beasts and spirituality, leading Russell down the rabbit hole and discovering the dirty, unkempt home where the beast-possessed father lives.

The manifesting generational scars are vividly depicted, both the Weavers and Meadows having to face wounds pierced by failing patriarchs. Cooper also keys into the insatiable hunger of capitalism that has bled this town dry, much like the beast who only wants to eat and eat, leaving the town underfed and creating a desperation that brings out the worst in its population. The body horror is magnificently disgusting and terrifying, with a clear influence from producer Guillermo Del Toro and some David Cronenberg shining through as antlers tear through human flesh. One scene, where an antler rips through the mouth of one of the bodies it possesses, is particularly memorable in its viscerality.

Cooper’s foray into horror slips up when it comes to the othering of indigenous people. Former Sheriff Stokes (Graham Greene), a Native American, is the one to discover the first corpse left by the beast and it is him who recognizes what evil tore through these bodies. But it’s also on him––in a strangely ineffective and laughable scene––to explain to the white people the reasons for this terror. What goes unfed will accordingly morph into a beast and kill. It adds no profound meaning to the story, ringing eerily similar to Cooper’s attempt at making a “racism is bad” film with Hostiles, where Christian Bale must overcome his bigotry. The myth-making of indigenous people is implied to be magical realism, a term most indigenous hate; to them, this is not magic but reality. So when Cooper shoehorns this lazy exposition into the last act, the narrative takes a misguided turn. Had the film been absent at this attempt of indigenous lore, the impact would’ve been the same. Instead Cooper creates another shallow trope of a people so often maligned in American cinema.

Antlers is at its best when grounded in familial trauma haunted by the mythical terrors of the beast. The mystery evoked by the eldest Weavers’ condition adds palpable unease, but it is ideas of the physical vs. spiritual, how families must overcome the worst of their scars to move on, that is most resonant. It’s not the first time Cooper has attempted to capture the scarcity of a disappearing town, but unlike Out of the Furnace––which had little to say beyond its lived-in setting––Antlers is mostly a success as it melds grounded blue-collar drama with chilling horror overtones.

Antlers opens in theaters on Friday, October 29.