The singular styles of filmmakers in the Woche der Kritik (aka Berlin Critics’ Week) often result in some of the year’s most under-appreciated and formally exciting cinema. I’ve covered this section of Berlinale for the past three years and each year, I find at least a few movies that I continue to think about long after watching them. The unfortunate reality remains that many of these films don’t find distribution or seem to get lost in the shuffle––especially the short films––because of their experimental nature. A few movies from the past few years I’d like to single out here as absolutely worth going out of your way to find and watch: Adam Khalil & Bailey Sweitzer’s Nosferasta: First Bite, Ekaterina Selenkina’s Detours, Manoj Leonel Jahson & Shyam Sunder’s Kuthiraivaal, and Kamal Aljafari’s An Unusual Summer.

Now for my favorites from this year’s edition:

The Demands of an Ordinary Devotion (Eva Giolo)

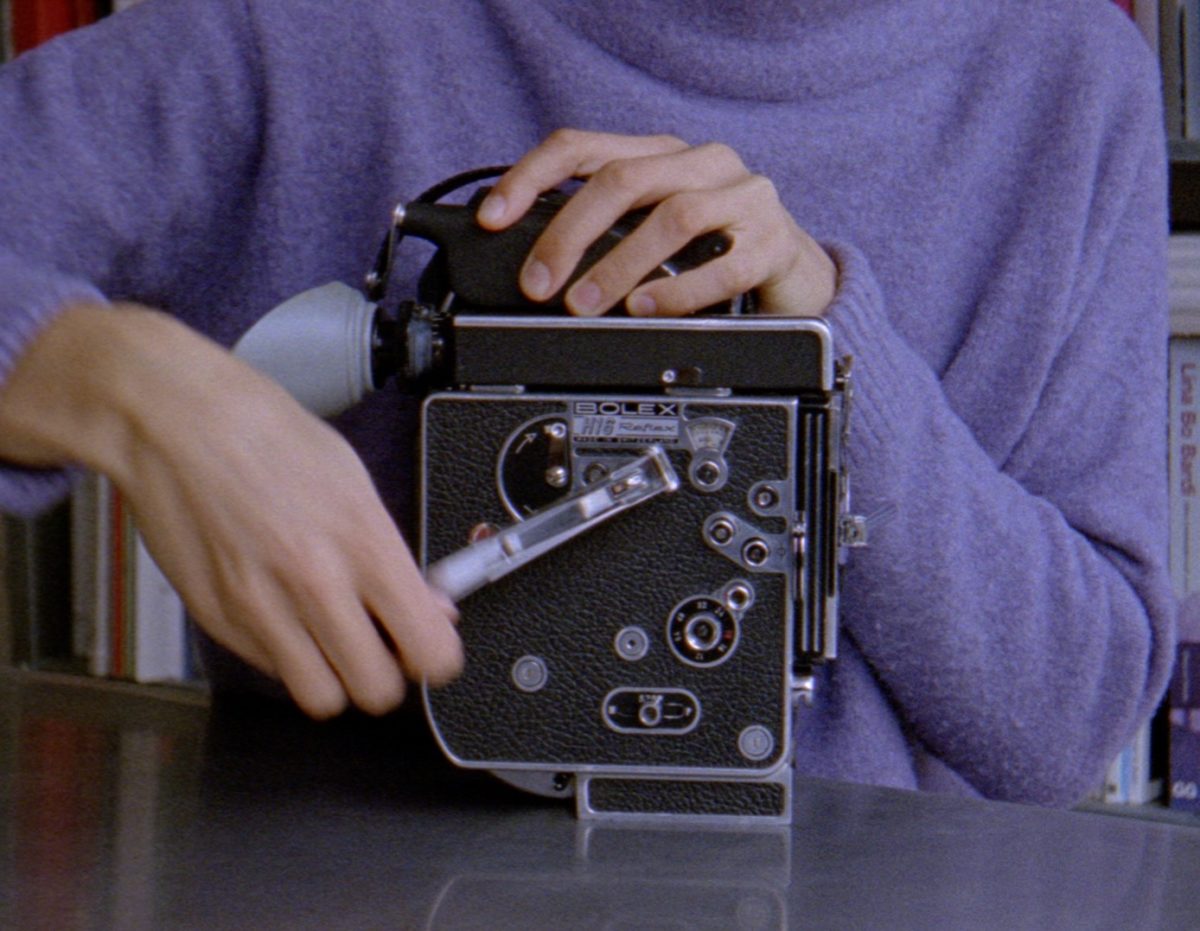

Beginning as it does with a coin flip, there’s plenty that can be interpreted from The Demands of Ordinary Devotion. It’s often said there’s too much importance given to solving movies rather than allowing them to play as they are on your screen. The natural human impulse is to make sense of images next to each other, and one can create automatic connections in Eva Giolo’s experimental montage movie with sexuality, birth, cycles, and chance. In this sense it isn’t a movie to “solve” at all––it lays bare the symbolic ritual of life and dependency of objects and things on each other. Its images and sounds harken to the passage of time within nature, the maturity of the cinematic image––its fruits––juxtaposed with the birth of new things. The pops, crunches, and pings of its various objects––a camera, a pomegranate being opened, a baby breast-feeding, a coin flipping––all signal the film’s own creation and birth and maturity over its brief 12 minutes.

The Fifth Thoracic Vertebra (Park Syeyoung)

Filmed like a fever dream with bright, stark lighting and a dreamlike haze, The Fifth Thoracic Vertebra mixes its eclectic form with nightmarish weirdness and a premise that automatically catches attention. A mattress becomes a place for discussing the ebbs and flows of a relationship. Once said relationship breaks, a fungus grows on said mattress and manifests into a being that feasts on the spine and fluid of those sleeping on it. The film counts down the days until the fungus’s birth as well as days of its life, and the mattress takes on a journey not unlike the tire in Quentin Dupieux’s Rubber.

Director Park Syeyoung focuses on the pacing in relation to this fungus’s lifespan. As the movie counts days of its life, it shifts between hyperfast timelapses and slow-moving sequences. The motions of the fungus and the colors representing its spread are a feat of independent production value, allowing the imagination to run wild, turning its attacks into a glittery psychedelic display of weird horror.

Koban Louzou (Brieuc Schieb)

A lot of talk of “what would be your job on the post-capitalist commune?” without considering the fact that communes are mostly boring and everyone has to kind of do everything to make them work. Koban Louzou, a film whose title is Internet-inspired (it means’ “Cottage Core”) is different from Ephraim Asili’s notable commune-film The Inheritance––its communal household is not aimed at any sort of educational or reformative purpose, but instead the muse of one awkward man to create a community of equal sharing away from everything else. Likewise, Koban Louzou‘s direction is less inspired by art and visual storytelling than the mundane ritual of it all. It also doesn’t feature any of the sensationalist drama from Nathan Silver’s Stinking Heaven.

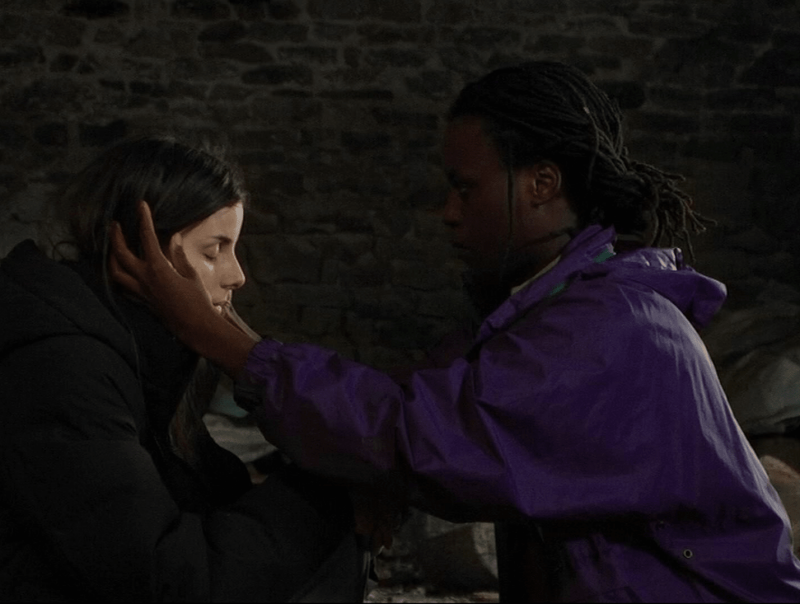

It’s a simple fish-out-of-water tale of Audrey coming to live in a commune of four other people––Kathleen, Laurence, Aymeric, and Baptiste––while trying to find her own place among them. The pressures of Aymeric, commune owner––he makes it clear he owns the place, but tries softening that reality by saying he feels everyone should consider it their house too––come in the form of a rather strict schedule adherent to doing chores benefitting the greater good. Brieuc Sheib’s camera merely seeks to observe the space, the direct relations of characters to each other. It’s an eclectic group and their communications with Elle forms naturally. One might be disappointed in how “realistic” or tonally tame Koban Louzou is, but it strongly turns the low-hanging fruit of Sartre’s “hell is other people” on its head––into a more understated character examination.

Lust (or Perfect Pair)

Listed as Lust in the Woche der Kritik catalogue but known as Perfect Pair, this film also has discrepancies in its credit. It’s listed as being directed by Valie Export, though in the film’s credits it’s “Value Export.” Perhaps this is a joke. In fact the whole movie is one elaborate gag––a detailed, inquisitive one at that. Made in 1986, it has as much of an influence from odd television commercials as David Lynch’s films. There’s a deliberate attempt to plaster the screen with consumerist iconography and a visual template that tries replicating the sexual melodrama of an ad desperately selling something cheap and tawdry.

More so, its overt concentration on the body––the price of it and sexual exploitation in capitalist consumer worship––is displayed in unabashedly obvious ways. A woman prices out various sexually active men and conduct for different price ranges; meanwhile, a bodybuilder she meets at a bar is filmed closely as his muscles and pecs bulge. If Export’s film may not have layered meaning, that’s the point: there isn’t anything layered or meaningful about the consumer mentality it depicts.

Shin Ultraman (Shinji Higuchi)

The influence of the original Ultraman series on Hideaki Anno’s career is obvious in both Gunbuster and the entire Evangelion franchise. As he did with the latter in his Evangelion Rebuilds, Anno returns to his influences in a new 21st-century light as writer of Shin Ultraman, a spiritual sequel to Shin Godzilla. Director Shinji Higuchi takes Anno’s script and creates a kinetic, jumpy canvas of radically disparate shot sequences––one side of characters to the next, under tables, over furniture, between arms and legs, and seemingly anything else. The manga influence on its aesthetic is clear, but in creating so many individual angles to cover the space characters inhabit, this is a rare film that visually illustrates the bureaucratic “office politics” of government response to disasters without making it feel boring. The human characters do almost nothing, but are in fact the heart and soul of the film. Monsters and fighting are filler.

The fights are fun but (deliberately) more conventional than the scenes of SSSP (S-Class Species Suppression Protocol, the government division responsible for strategizing against kaiju attacks) members sitting around on their computers trying to calculate the next attack. Higuchi films the office banter like intense battles and Anno’s script features his patented “tell-all” style of dialogue, never mincing words on the metaphorical connection between the kaiju and Japan’s history with devastating earthquakes and wartime tragedy. Together, Anno and Higuchi create a movie that, while not bearing quite the magnitude of pulse from Shin Godzilla, presents a spirited, fun follow-up in this series looking back on and revamping Japanese media’s most iconic characters.