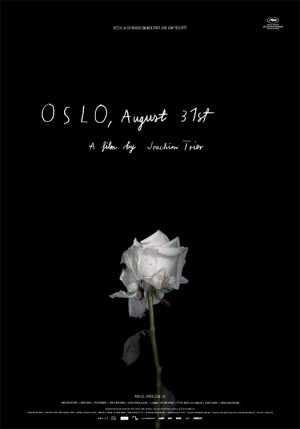

Memory and nostalgia—these are the things Joachim Trier sought when creating his dark, hopeful and depressing love letter to his hometown. Rather than use that word, however, he made a point in his Q&A at the Toronto International Film Festival to call it the place he was born. Every city in the world is remembered by its citizens and ex-pats. They reminiscence about good times, how they felt, or how they miss it. The opening to Oslo, 31. august [Oslo, August 31st] is a collection of these tales—memories and recollections associated when hearing the city’s name. A montage of home videos and footage from some of Trier’s favorite Norwegian films set to the words of interviewees fondly looking back, we become set at ease awaiting a sweet story to unfold. But Trier and Eskil Vogt’s script, based on the novel Le feu follet by Pierre Drieu La Rochelle, has a different idea as a parallel path towards melancholy unfolds.

This isn’t a huge surprise, though. Trier knows melancholic characters well and showed as much in his brilliant debut Reprise. So when the final video shown in the montage is of a voice remembering the Phillips Building’s demolition, we watch it fall from multiple angles, one from the side of the structure itself. All the idyllic imagery is gone in a flash and replaced by the pensive look of Anders (Anders Danielsen Lie) staring into the distance as his Swedish lover Malin (Malin Crepin) lays nude under the covers. This is a young man whose memories of home don’t quite hold the same happiness as our own. He had fun, that is for sure, but the cost of his joy was an inability to remember it clearly. Whereas many dive into their past and hope to rekindle friendships or bolster ones that still exist, all Anders has are the painful memories of what his addiction did to the ones he loved.

Yes, Anders is a recovered drug addict on the cusp of release. With two weeks left in his stay and a current 10-months of sobriety, he hoped a night with Malin would have helped put him on a road to normalcy. Sadly it didn’t. Only serving to stir up the not so dormant feelings possessed for Iselin (Iselin Steiro), the love he pushed away, he finds there is nothing left. The drugs destroyed him and now their absence cultivates a yearning to escape reality. He’s lost years of his life to addiction, a gaping hole on his resume that scares him more than prospective employers. What chance does he have in finding a future? What chance is there for the ones he hurt to forgive him so he can find peace? These are questions he would rather not find an answer to while trying to drown in the lake behind his rehab facility. But his self-loathing isn’t heavy enough and a return home becomes necessary to make sure his loved ones know he died of his own accord.

So Oslo becomes a document to one man’s mistakes and the people he touched. Anders has no grand plan for his return, only wanting to see those he cared for to let them know he was clean, but still in pain. Depression filled the void heroin left, warping his bucket list into one completely filled with goodbyes. As a girl he overhears in a coffee shop speaks aloud her own itinerary of swimming with dolphins, finding love, or creating something memorable, Anders can only laugh at the innocent goals of a naïve girl unaware of how hard life is. It’s not as though Anders has the worst life in the world either, he still has people who love him. But how much of that love is rooted in pity? How much is disingenuous and pandering? Trier contextualizes his lead with the boring lives of other to show how the mundane is cruel too. Anders can’t help them, though, just like he can’t help himself.

Utilizing some of the same stylistic flourishes from Reprise, Trier is able to visually place us inside this tragic man’s head during the time between August 30th and 31st. Moments of out-of-synch footage go by, passages continuing to be spoken while the imagery jumps forward to a place of silence. We watch Anders run into old friends, their anecdotal stories that should be funny only pushing him further into the dark depths of self. A new girl brings spontaneity while submerging him into memories of Iselin, his parents selling their home becomes a final loss of childhood, and his own sister refuses to meet him, afraid his release means it’s only a matter of time before the drugs start again. A touching bit with an ex-girlfriend in Mirjim (Kjærsti Odden Skjeldal) goes too far, the escapades of an old friend Petter (Petter Width Kristiansen) threatens to lead him back into drugs, and everyone’s success compared to his emptiness becomes unbearable.

Brilliantly orchestrated, Oslo is a powerful work that’s hard to believe took only four months to write and a year to complete. Trier is a master at handling emotion and aesthetic, the chaotic blur of a club scene’s booming bass juxtaposing with the quiet storm of regret in the teary eyes of Anders. The subject matter may be a downer, but somehow the film shines with a glimmer of hope. Even when it appears all is lost, death his only release from past mistakes, we hold onto the possibility he’ll find something worth living for. In a genuine and memorable sequence, Anders talks at length with an old friend named Thomas (Hans Olav Brenner), their pasts taking different paths. We listen to Thomas talk about his domestic troubles, trivial when compared to his hurting buddy, and can’t help laughing. It’s just one of many examples that prove no life can give him what he desires. No life will help him forget—thoughts of Oslo, Norway holding nothing but tragedy.

People enjoy saying things will be alright, but deep down they know it’s impossible. Happiness will always come at a price and some of us sadly reach the point where they aren’t willing to pay it anymore. But that doesn’t mean life was wasted, and I don’t think Anders would have looked at it that way either. Danielsen Lie’s performance gives it the internalized struggle needed to understand his pain. And it is completely visceral as Trier captures every ounce of emotion available to him on screen. After the screening he talked about his country lacking the icons of his Scandinavian neighbors, but I think he may soon be wrong. If his first two films are any indication, Joachim Trier could very well be that cinematic voice Norway can be proud to share with the world.