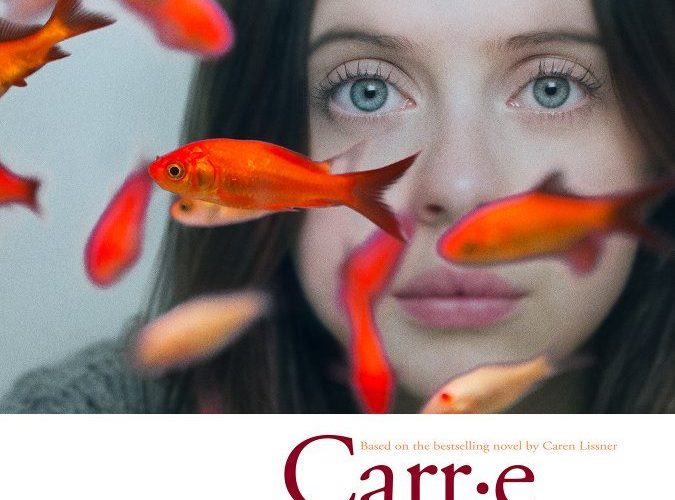

The synopsis for Carrie Pilby can sound atrocious on paper. Most films utilizing an eighteen-year old Harvard graduate do so as periphery color because the trope lends itself to obnoxious pedantry and an unsympathetic notion of “first world problems.” Having your titular lead (played by Bel Powley) be that person is therefore a risky proposition. She’s an introvert bagging on society for willingly lowering their IQ to fit a cesspool of mediocrity despite making no attempt to engage or discover whether that assumption is true. We should despise her and harbor frustration towards director Susan Johnson for wanting the opposite. Well the joke’s on us because her character proves utterly likable in her failings — likable and relatable while traversing the landscape of life and love.

Her identity is in shambles after a year off post-college in her adopted home. With Dad (Gabriel Byrne) refusing to leave London (she refuses to leave New York), Carrie’s “parental figure” of sorts is his friend and her psychiatrist Dr. Petrov (Nathan Lane). It’s actually not a horrible situation because he knows her beyond the prickly sarcasm and breathless desire to hole-up in her apartment rather than allow the air of superiority she cannot squash push more people away. He knew her mother before she passed (catalyzing the journey across the Atlantic) and knows the pain she feels despite not vocalizing or accepting it. He knows her shortcomings and insecurities stem from sadness that only human interaction can cure. So he gives her “homework” to do exactly that.

It’s time to indulge in cherry soda, revisit her favorite book (Franny and Zooey by J.D. Salinger), get a pet, and perhaps make a friend. It’s time to be happy despite the troubles her looking off into the distance provides via emotionally wrought flashbacks of a trust gone wrong that completely shut her life down. However, being a 185-IQ savant with a photographic memory and unwavering moral code means that crossing assignments off Dr. Petrov’s list is only going to happen on her terms. So she’ll try to befriend her eccentric bunch of legal proofreading coworkers on the overnight shift and attempt going on a date with an engaged man buying classified ads to “see if he’s making the right decision” (Jason Ritter‘s Matt) merely to out him.

Novelist Caren Lissner‘s story (adapted by Dean Craig and Kara Holden) isn’t without cliché or convenience, but it possesses enough heart to combat them. Saccharine lines purporting that love is knowing your significant other’s middle name come back in inauthentic ways, but the sentiment works if execution doesn’t. Some revelations like why Dad is staying in London feel tacked on for added emotional fireworks, but when the character explains his reasoning it does make sense. Behind everything is Carrie’s inability to let loose and take things at face value and those who she can trust have been bred to act accordingly. Strangers too for that matter — they either dismiss her as the lonely weird girl or rise to the challenge of breaking her from her shell.

The latter comes from fellow graveyard shifters Douglas (Desmin Borges) and Tara (Vanessa Bayer) as well as her always more-than-meets-the-eye neighbor Cy (William Moseley). They keep her on her toes and break-up her routine, refusing to take her default abrasiveness personal. It’s as though no one had ever been nice to her in her life and suddenly everyone she meets is. Yes this feels poorly manufactured, but the goal is to provide Carrie growth. Maybe people had been nice before and she simply rebuked them out of turn (see the possibly flirtatious waiter from the beginning). Maybe it’s only when she has cherry soda in her belly that she can build rapport in a way that makes us wonder why she isn’t swarmed with friends.

The simple answer is a tragic past of familial struggles and predatory wolves to which she’s the first to admit complicity where earned — an action that may actually hurt more than help. Only now is she affording herself the opportunity to heal through catharsis and a little side of revenge. It’s a captivating process considering how quick she is to project her values on a world that scoffs at them as “goody-two-shoes.” Carrie isn’t afraid to call a hypocrite a hypocrite unless it’s herself (she’ll warm to that eventually), so her predicament is ultimately a result of pre-judging others based on disappointments already endured. But as Petrov tells her: only by giving someone a chance can he/she surprise her. She’s not the only nerd in NYC.

The journey towards this reality comes as a way to accept the past as much as embrace the future. It’s about opening her eyes to the fact that things are more often gray than black and white. This evolution won’t be easy or without backsliding into the knee-jerk reactions of old Carrie jumping to conclusions without considering what’s happening beyond the surface she sees, but it will be fruitful. Some people will prove nothing like her assumptions and others will be worse, but it isn’t her job to fix them. She can’t help looking at the world as victims and jerks, writing everyone off sight unseen despite both being fitting labels for her too. Life is messy, no one is perfect, and there’s nothing wrong with either.

Lane is a standout as Petrov, each scene opening with internal conflict before switching to psychiatrist mode and putting his own troubles away. Borges and Bayer are zany enough to offset Carrie’s killjoy; Byrne received a couple moments to be more than just a voice on a phone. Ritter comes in as an intriguing conundrum to show Carrie how intelligence doesn’t always equal purity and Moseley lends his Renaissance man more character than the somewhat shallow role probably deserves. Despite the performances being worthwhile, though, it’s difficult not to more or less see each as a pawn. Carrie reacts to them and they do pretty much exist solely for those reactions. It’s easy to forgive this because that’s the film’s point, but the convenience does prove irksome nevertheless.

Thankfully Johnson got someone like Powley to take on the central role because it’s through her honesty that we allow the rest to be somewhat two-dimensional. She expressively travels their gauntlet of flaws and truths, relenting to their demands for her to let go as much as refusing them. Even though Carrie allows herself to ease up on certain aspects of who she is, her core moral code is immovable. The film doesn’t let her corrupt herself; it merely allows her to be okay with those around her doing corruptible things — no matter how emotionally-fueled and devoid of reason their life choices are. Acceptance goes a long way in this world. If you’re okay acknowledging others are deeper than first impressions, they may just return the favor.

Carrie Pilby premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival and opens on March 31.